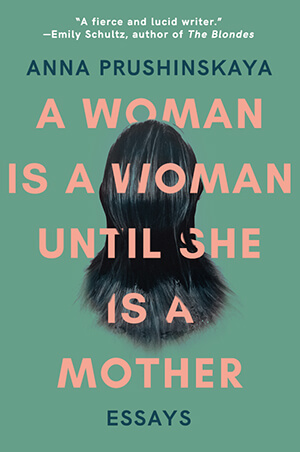

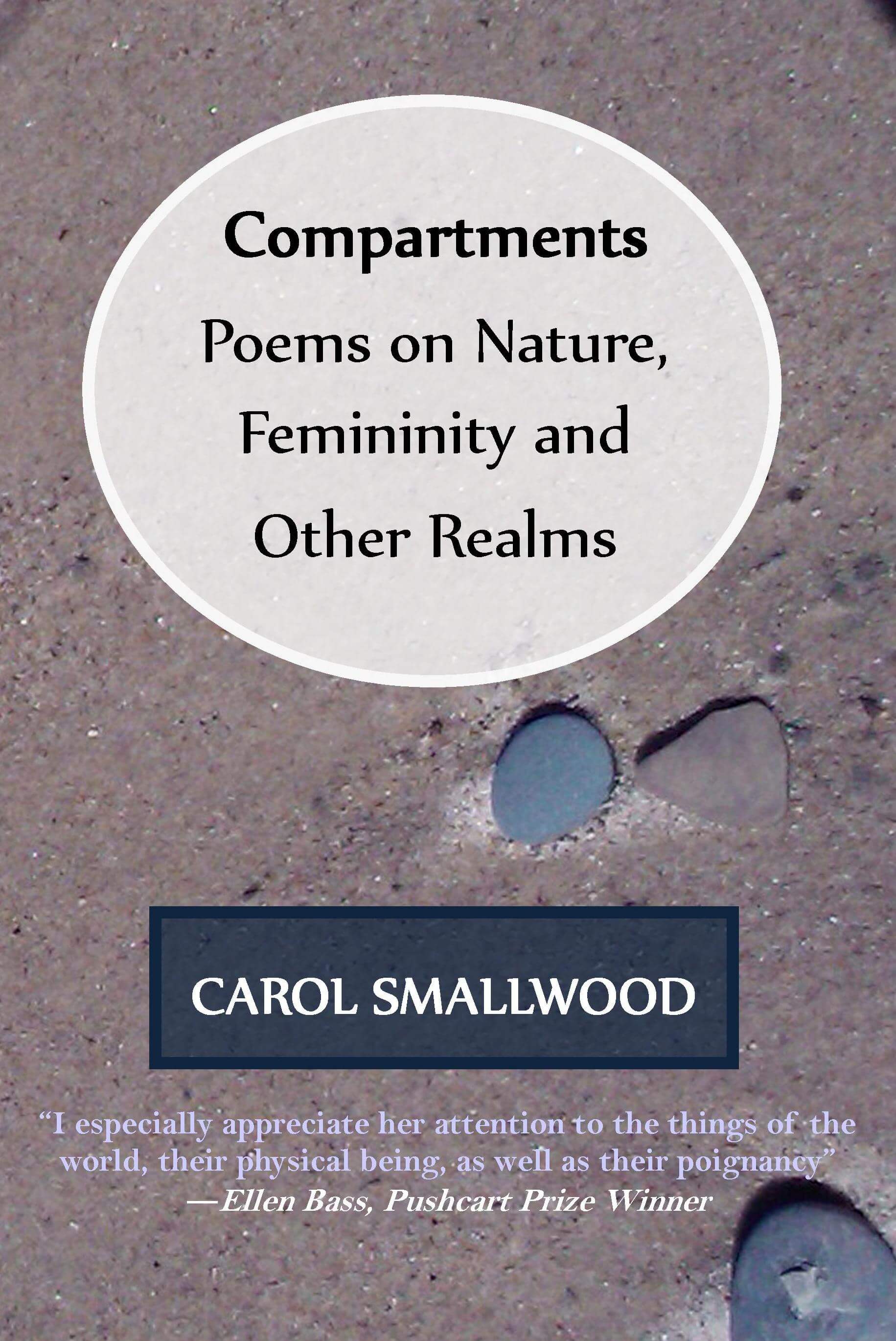

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Carol Smallwood about her book Compartments: Poems on Nature, Femininity and Other Realms, the subconscious roots of writing, working with formal verse, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Carol Smallwood about her book Compartments: Poems on Nature, Femininity and Other Realms, the subconscious roots of writing, working with formal verse, and more.

**

Sydney Cohen: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Carol Smallwood: My connection to the Midwest goes back to homesteaders and I’ve always lived in Michigan and my children also live in Michigan.

SC: During your career as a librarian you wrote and published works that provided guidance and advice to other librarians in the field, including outreach programs and budget-saving methods. What changes did you work to implement in the field of library science, and how do you believe this field has evolved since your time as a librarian?

CS: My first book was on Michigan resources after teachers asked me what was out there to use for Michigan Week. There was so much available that was free it ended up being published by Hillsdale Educational Publishers and it was followed by an updated edition. The library field has of course been impacted by technology like every other profession and I was part of doing away with the card catalog and setting up the collection online.

SC: Your book of poetry, titled Compartments: Poems on Nature, Femininity and Other Realms, addresses varying spheres of life spanning from nature to domesticity to mortality. How did you go about tackling such a diverse breadth of topics in your collection? Is there a common thread running through each realm of your book?

CS: The title was used because that grouped the topics of the poems I’d already had written and which are really related to one another. Using a foreword, introduction, prologue, epilogue in my poetry collections is probably a reflection of being involved with nonfiction.

SC: Your newest collection, Prisms, Particles, and Refractions, blends together the seemingly disparate worlds of art and science. Your writing explores the metaphorical and literal texture of light in three sections that put physics and poetry in conversation with one another. What was your inspiration for writing this collection? What, if anything, did you discover about art or science that you did not know before?

CS: As a fan of astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, I was made even more aware in the meeting of science and philosophy. As he noted: “We are part of this universe; we are in this universe, but perhaps more important than both of those facts, is that the universe is in us.” It is exciting to live in times that have made such strides in the exploration and understanding of the cosmos. In Hubble’s Shadow (Shanti Arts, 2017) also examines the influence of discoveries. Understanding the human brain is also an exciting new frontier.

SC: The Midwest plays an important role in your family history, with your lineage rooted in Michigan. How does the Midwest feature in your writing, whether overtly or subtextually? What works of yours do you consider particularly Midwestern?

CS: We cannot get away from where we’re from: even the composition of our teeth is directly related to water as a child and our culture is so much part of us we do not see it. As far as using the Midwest in titles, I wrote an essay, “Midwestern Spring,” about the coming of the season in the Midwest for Interweavings: Creative Nonfiction (Shanti Arts, 2017). I edited the third edition of Michigan Authors—the last print edition before it became a Library of Michigan and Michigan Association of Media in Education database online: authors and illustrators are eligible for inclusion in Michigan Authors and Illustrators if they are born in Michigan, live or have lived in Michigan or have works about or set in Michigan.

SC: You have written an extremely impressive and extensive array of works, including poetry, fiction and nonfiction. What do you find is the most challenging aspect of the writing process? What comes easily for you?

CS: Nonfiction was what I started with, then I did fiction, then poetry. The most challenging is finding what you want to write about, or rather what you are capable, ready to do. Most writing I believe happens in our subconscious, that subterranean wild place of dreams: it is at odd times it pops out when it isn’t convenient, like when driving, trying to fall asleep. Brooding (often not knowing it) brings about the most finished work, that is, much of it has formed and you just need to let it go into words even if it only begins with a line, a concept.

SC: In the film industry, directors who have achieved a large amount of success are sometimes afforded a “blank check,” which they use to create whatever projects they want. As a writer who has achieved immense success and acclaim, do you find you have the agency and professional backing to create your own passion projects?

CS: Unfortunately, the poetry I often use is the formal or classical kind such as the pantoum, villanelle, and others, and editors sometimes prefer free verse, that is, nothing with rhyme and form. My poetry collections combine forms to appeal to different taste and am composing the rondeau now with the help of the great paperback: How to Write Classical Poetry: A Guide to Forms, Techniques, and Meaning

As far as library anthologies, they are topics I know will be popular, serve a need, and sometimes co-editors or publishers suggest topics; after editing, writing, or co-editing over five dozen, they still are enjoyable as librarians come up with wonderful work.

SC: When teaching English, what was the most important piece of advice you would tell your students?

CS: Read closely and be curious about word choice. I remember in the second grade the wonder of words came to me when the reading book had the word “suddenly” after all the one syllable words. It had power, mystery, was grown up, and couldn’t believe words could have such musical magic.

SC: If you could sit down with any author or book character, from any point in history, who would it be? What would you discuss?

CS: John Galsworthy is the one author I would really like to meet after reading him since high school. I’ve got most of his short stories, plays, essays, novels and keep learning from him. Over and over his novels never lose their relevance—the Nobel Prize Winner died before I was born but the world he creates is a place always new.

SC: What’s next for you?

CS: Next is more library anthologies and poetry collection under contracts. Hopefully another poetry collection now making the rounds will be accepted: A Matter of Selection and another collection inspired by a quotation is underway. I enjoy doing interviews more than book reviews and as poetry judge for the Women’s National Book Association am helping spread the word about its 2018 Writing Contest. Thank you very much for this opportunity.

**

Carol Smallwood’s over five dozen books include Women on Poetry: Writing, Revising, Publishing and Teaching, on Poets & Writers Magazine list of Best Books for Writers. Recent anthologies include: Writing After Retirement: Tips by Successful Retired Writers (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014); Bringing the Arts into the Library: An Outreach Handbook (American Library Association, 2014); Water, Earth, Air, Fire, and Picket Fences (Lamar University Press, 2014), Divining the Prime Meridian (WordTech Editions, 2015).

Her most recent literary collections are: Interweavings: Creative Nonfiction (Shanti Arts, 2017) and In Hubble’s Shadow (Shanti arts, 2017). Prisms, Particles, and Refractions (Finishing Line Press, 2017). Library Outreach to Writers and Poets: Interviews and Case Studies of Cooperation (McFarland, 2017);and Gender Issues and the Library: Case Studies of Innovative Programs and Resources (McFarland, 2017). Carol has founded and supports humane societies. She’s received multiple Pushcart Prize nominations and appears in Who’s Who in America; Who’s Who in the World, Wikipedia.

December 15th, 2017 |

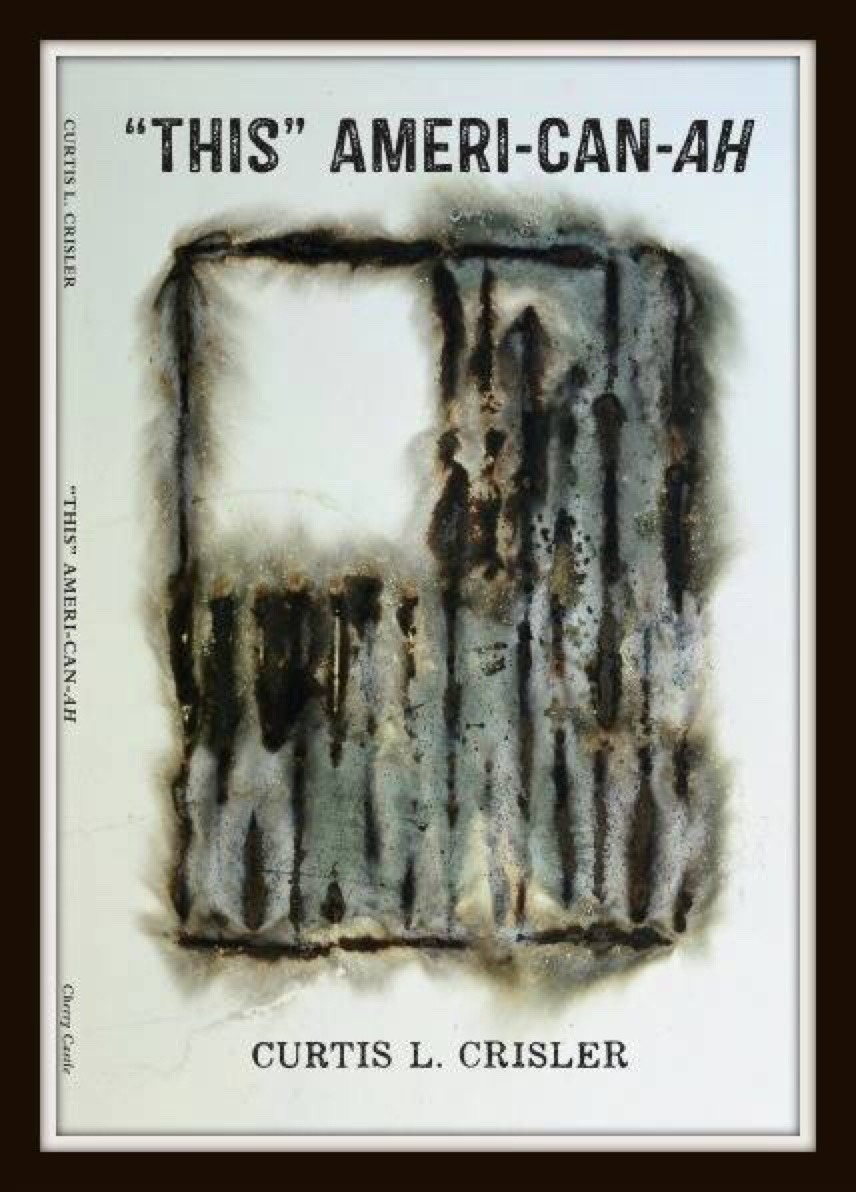

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with poet Curtis Crisler about his collections THe GReY aLBuM [PoeMS] and “This” Ameri-can-ah, pop culture inspirations, the relationship between poetry and theater, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with poet Curtis Crisler about his collections THe GReY aLBuM [PoeMS] and “This” Ameri-can-ah, pop culture inspirations, the relationship between poetry and theater, and more.

**

Sydney Cohen: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Curtis Crisler: I am a Hoosier. I was born and raised in Gary, Indiana, a.k.a. “Little Chicago” when I was growing up—part of the tri-states—Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana. Now, I live in Fort Wayne—the second largest city in Indiana.

Also, to chronicle urban Midwestern life, I have coined “urban Midwestern sensibility (uMs).” An uMs “examines the Great Migrants who’ve migrated from the south to the north, from about the time of 1915 through the 1970s (even though some have written it wasn’t a fluid migration, but more broken up into two periods). Urban Midwestern sensibility examines the black migrant’s past, present, and future.” I am now submitting the manuscript, Playbook for an Urban Midwestern Sensibility (Crafting Work Cross-Genres), for publication. It is a book on craft, and “illustrate[s] my vision, through craft, and what an ‘urban Midwestern sensibility’ (uMs) fully encompasses through the genres of poetry, fiction, drama, and essay.”

SC: Your upcoming book of poetry, THe GReY aLBuM [PoeMS], is a playfully inventive manipulation of form and sound with influences from history and pop culture. What was your inspiration behind the collection? Which pieces do you find particularly moving, and why?

CC: My initial inspiration was a manny (manuscript) I was submitting and trying to get published called The Black Album [poems]. It was a play on all The Black Albums done by artist like Prince, Jay-Z, and Metallica that played off The White Album of the Beatles. It did make it to the finals of the 2014 Omnidawn Open. After that, I put the manuscript away. I was thinking I wouldn’t publish it, and maybe after I died, it could be one of those treasures found and later released. A couple of years later, and the death of Prince, connected me to myself. What I mean by that is that I feel I live in the grey area of life, not the black or white so much. So, I put together THe GReY aLBuM [PoeMS], writing some new poems to replace some in the original, The Black Album [poems], and I dedicated the manny to Prince. I wanted to address my headspace on the times, the passing of one of my favorite artists, and poems that wanted to play in the ether of existence. So, I let them loose.

I feel all the pieces are moving in THe GReY aLBuM [PoeMS]. In the first section, called “Grey Hot Tracks,” the first poem, “Living in Grey Matters (a pattern),” along with the poems, “living in the grey matter cento,” from the third section, and “Living in the Greyz Redux” (the sixth and last section), are three poems that were seminal to a thematic lyrical throbbing of me living in the grey matter (this life). These three occurrences (poems) were detrimental to the book’s existence. These three sections pulse in a reality that is so uber-realistic that they become surreal. Also, the first poem, “Living in Grey Matters (a pattern),” addresses how we are desensitized to people being killed on video due to technology, and how it renders such a disassociating occurrence to many that the effect of death seems tame in our social construct. The poem ponders an implied question I can’t seem to answer, Why can’t some trained police officers get an unarmed person from point A to point B without them ending up dead? The poem goes on to pose more philosophical questions we never seem to reconcile. The “re-” throughout the poem plays on the denotation of the prefix: 1) indicating return to a previous condition, restoration, withdrawal, etc.: rebuild, renew, retrace, reunite, or 2) indicating repetition of an action: recopy, remarry (dictionary.com). For me, the recurrence of killings in our public space is not a reoccurrence but a continuation, and we can view the loss of lives like tutorials on YouTube. Yet, it’s nothing new, especially from a musical representation of brutality—good, bad, or indifferent. From Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar to Tupac and Biggie; from Public Enemy to NWA and Ice-T; from Prince and Sweet Honey in the Rock to Marvin Gaye and the Temptations; from Jimi Hendrix to Aretha Franklin to Stevie Wonder to Sam Cooke to Nina Simone; from Billie Holiday to Paul Roberson; to Mahalia; to Armstrong, back to Buddy Bolden and King Oliver, back to Robert Johnson and Lead Belly; back to the slaves moaning in the cotton fields, there has been music about the conflicts between blacks and many of the authorities in America.

The second section, “The Grey Singles,” makes the surreal real. The fourth section, “Top 10 Greyz,” is like dreaming underwater. And the fifth section, “The Grey 12-inches,” springboards romantically through the lens of Junior’s song “Mama Used to Say,” and represents the most linear theme within the book. The combination makes for a great conception album—I think, but I could be crazy.

SC: You graduated from Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne with a minor in Theater. As poetry is largely a performative art, how does your theater training play a role in the way in which you write, understand and share your work?

CC: The mechanics of performance: stage presence/awareness, articulation, projection, breathing, and body control—the body as an instrument—is so apropos in theater and poetry. The poem works through the body, lives there, and then is released like breaths a woman has when giving birth. If Betty Davis really said something to the extent that acting is being on stage naked, and slowly turning around, I feel her statement embodies poetry as well, where you get to see, hear, feel, the truth of words coming to life. Like Lucille Clifton, I am open to poetry, so poetry comes to me. Also, like a friend and poet, Eric Baus, I am obsessed with the poem, the object, the subject, the words, until I’m not. The call to write can come at any time, and usually does, but just like theater, you live with a character, become the character, know the character, the same can be said with a poem. Maybe it’s why I believe when my books are published that they are my children graduating from high school, and going out into the world—some go to college, work at libraries, bookstores, middle schools, high schools, travel overseas—some have fast tongues—some are clever and slow—some don’t care what you think of them—some just want to look you dead in your eyes, and say, “Hey,” just so you can feel their breath on your face.

SC: Another one of your collections, “This” Ameri-can-ah, is comprised of eclectic and humoristic poems that work to illustrate American life. How does your writing subvert, or reaffirm, notions of “American” poetry? How does your work contribute to the discourse around what it means to be American? In your definition, what is Americana?

CC: “I have always been enamored by the relationship/s of man and woman, woman and woman, woman and child, woman/man and son/daughter, man and animal, nature and nurture, poor and privileged, the ‘other’ and the status quo, religion and science, sci-fi and comics, insider vs. outsider, and so on. This comes from examining my surroundings—the people around me, the environment around me—my community—local, regional, and global” — Playbook for an Urban Midwestern Sensibility (Crafting Work Cross-Genres). America is built on relationships, good, bad, indifferent. Along with all the controversy of our differences, we tend not to notice the things that make us alike. We trust each other more than we think we do: think driving, and for the most part, everyone doing what they need to do to get to where they need to be—most times this happens without fault. Think buying food from grocery stores, farmer’s markets, restaurants, etc. Even when things go badly, say we get in a car crash, or meat, milk, and vegetables get tainted with something bad, for the most part it is a blip on the screen of our lives in the milieu of all the people that make up America. That’s not to say that people don’t die or get maimed in car crashes, or that people don’t die and get sick from viruses. Yes, those can and do happen, but far less than we think. Most Americans have access to the above mentioned; still, many don’t. I worry about them. I believe America is both circumstances: being alike, functioning alike, for most of us, but the other side of the coin are those who aren’t in that majority—they have problems functioning (be it inadequate education, job opportunities, housing, health care, lack of viable transportation, living in food deserts, etc.) compared to their counterparts.

The Americana part, for me, is how we manage to get through this messy existence. Somehow, we do get through it, or we don’t get through it, or we just keep trying to get through it—living with the memory of it all.

SC: Your poetry is rife with historical and pop cultural references. Which cultural figures inspire you the most? Is your integration of these figures conscious or subconscious? What work do these references do to ground a poem in a specific historical or cultural moment?

CC: I wish I knew which cultural figures inspired me the most, but I’m always moved by a person’s artistry, and how a person does what she/he does. I wouldn’t know who would come up in a poem, per se, until I was conceptualizing the poem. For example, with “Richard Pryor and me,” I have always felt Pryor shifty when too many people were around, but when it’s just us (that us is me, but it’s a universal we too)—with us, he could be real. And, it felt like he was more real on stage than he could be in real life. With “Boxing Arethas,” Aretha Franklin’s singing knocks it out the box, and is home as well because she connects me to every house I’ve ever lived in, and reminds me of weekends, and my mother. Aretha’s singing places me, viscerally—is happy, dark, soothing, angry, and punchy. She shows up in the last section of the book too. Prince died. Wow! Prince, M.J., and Madonna were all born in 1958. I was born 7 years later. M.J. died in 2009. Prince died 7 years later. If Madonna dies in 2023, I’m done. I won’t know what to do with all the 7s (thinking of Prince’s song as I say this).

I can’t say if it’s conscious of unconscious—probably a combination of both, at least in the case with Prince for this book. An exception would be my book Don’t Moan So Much (Stevie): A Poetry Musiquarium (Kattywompus Press). It is a book with poems of wonderment and praise for Stevie Wonder.

I am at a time in my life where family members, friends, peers, and the cultural figures I grew up with, die. That’s just a fact of life, and one that sucks. I think people can see death has a huge presence in this book, and it does, but in many interesting ways—death turns people into birds, has us reneging on our dietary choices when we become zombies, has your Greek teacher and his son sharing pie with your grandmother, has you not calling Stuart Scott back in time, or has you visit Donny Hathaway’s daughters in verse. How I got to these gems took a lot of mining. Death and Life are symbiotic. But sometimes, I’m like, “DAMN!”

SC: What are the greatest challenges to writing poetry, and what comes easily to you?

CC: I think the weirdest thing that challenges me the most is when I finish a project. I always feel like I will not be able to do anything productive again. And, since I address books like they are my children, maybe subconsciously I feel another child is out of the question. This is rather scary to think that it is all gone—verve, creativity and the like. Yet, the lady in my head gets me going again and again and again, until she tells me we have a baby on the way. That’s crazy, right?!

Unfortunately, the things that come easily to me are my mother’s voice and those voices that live in the margins. My mother’s voice works like a tuning fork for me. The voices in the margin, I feel like I speak for them, or that I have a platform where they can be heard. Narratives are always there, I just need to pay attention to them. Like I stated earlier, I really enjoy writing about relationships.

SC: What is your ideal writing environment—the sights, sounds, and smells?

CC: Okay, this is weird, but I’m going to answer this with an answer I gave to Chris Rice Cooper for her blog, “Celebrating 20 years of National Poetry Month from Around the Globe: 113 Poets on Sacred Spaces, Sacred Places…” I was one of her featured 113 poets on April 6, 2016. She posed a question, like yours—

What is your sacred space/place where you do most of your writing? Describe that sacred space/place using all of the five senses.

Now, I can write anywhere. I think you have to be mobile, and with our new technology, I can wake up out of the night and text myself on my phone when I get one of those images or lines of words that bombards my subconscious. I’d just like to state that first, but I do have a favorite place to write. My favorite sacred space is laying on my couch. I’ve always wanted a couch where I can relax or fall to sleep on after a long day of work, after a good workout and, a couch that accepted my body and wanted me there. I have that with this couch. When writing, I am adorned with my fantabulous throw cover and a myriad of pillows holding up my head and my legs for the most comforting experience I can have while writing. This way, my circulation doesn’t get cut off like when I’m sitting in a chair at my desk. I love the noise of the wind moving the trees to the left of me, as I hear birds, squirrels, cars, and voices in the distance, or just the moaning of my abode when the snow, rain, and sun encroach and play upon it. The environment around me plays heavily on my writing experience, for I know when I need something, and I can’t see it or hear it, I open my senses to where I am, and my environment comes rushing in with answers. But there is the ultimate experience, like when I’m in the zone. I have completely become one with my couch and my stirring for a more comfortable position as I type and type with a madness and the words that I will fuss with like a wife and husband fussing over finances. When in the zone, all sound is lost, and there is a whiteness around me (as best as I can express/explain it), and the couch is the foundation of where this takes place. For example: I always tell my students, and audiences now, that Black Achilles (Accents Publishing: an independent press for brilliant voices) was written on my back, with my left leg on top of the back of my couch since I had to have it elevated to control the swelling after my Achilles tear. My mother was in one of my comfy rocking chairs to my right, talking to me, talking on the phone, talking to the television, eating, snoring, and caring—the music of the chapbook, and a once in a lifetime experience. That is the truth! No need to embellish. Mama is my love. Also, there’s nothing like waking up out of the zone, or a needed nap, with the imprint of decorative pillows or couch on my face. Somehow, when I do come back to life, it’s the smell and feel of the couch, and the requisite markings on my face, arms, and legs that let me know I’ve put the work in. I then sigh, and murmur into the day, or night. I need to write an ode to my couch—give my couch a name.

SC: What’s next for you?

CC: I am working on quite a few things. THe GReY aLBuM [PoeMS] will be a new kid on the block, so I will be marketing and promoting it heavily through interviews like this, readings, etc. I have another book coming out, Indiana Nocturne(s): Our Rural and Urban Patchwork that Kevin McKelvey and I have been working on for around 10 years, give or take. Kevin is from Lebanon, Indiana—a rural farming area, and I am from Gary, Indiana—an urban city area. We are friends, and met in grad school at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Our book brings our rural and urban histories together, through poetry, and illustrates that even with our differences we are Midwestern and Hoosiers. Oh, we will also have an artist from Indiana who will do the artwork for our cover. We wanted to keep it all in house, so to speak. Playbook for an Urban Midwestern Sensibility (Crafting Work Cross-Genres) is a book on craft the elaborates on my urban Midwestern sensibility (uMs) through poetry, fiction, drama, and essay. Currently, I am looking for places that would be a good fit for Playbook for an Urban Midwestern Sensibility (Crafting Work Cross-Genres). The last thing that I am working on is a young adult book called Cheetah and Earl. I hope to start submitting that to places soon.

**

Curtis L. Crisler was born and raised in Gary, Indiana. He received a BA in English, with a minor in Theater, from Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne (IPFW), and he received an MFA from Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Crisler’s book, THe GReY aLBuM [PoeMS], was picked by Steel Toe Books for their 2016 Open Reading Period, and will be published in 2018. His recent poetry books are Don’t Moan So Much (Stevie): A Poetry Musiquarium (Kattywompus Press) and “This” Ameri-can-ah (Cherry Castle Publishing). His poetry chapbook, Black Achilles, was published by Accents Publishing. His previous books are Pulling Scabs (nominated for a Pushcart), Tough Boy Sonatas (YA), and Dreamist: a mixed-genre novel (YA). Other chapbooks are Wonderkind (nominated for a Pushcart), Soundtrack to Latchkey Boy, and Spill (which won a Keyhole Chapbook Award). He is the recipient of a residency from the City of Asylum/Pittsburgh (COA/P), the recipient of fellowships from Cave Canem, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts (VCCA), Soul Mountain, a guest resident at Hamline University, and a guest resident at Words on the Go (Indianapolis). Crisler has received a Library Scholars Grant Award, Indiana Arts Commission Grants, Eric Hoffer Awards, the Sterling Plumpp First Voices Poetry Award, and he was nominated for the Eliot Rosewater Award and the Jessie Redmon Fauset Book Award. His poetry has been adapted to theatrical productions in New York and Chicago, and he has been published in a variety of magazines, journals, and anthologies. He edited the nonfiction book, Leaving Me Behind: Writing a new me, on the Summer Bridge experience at IPFW. He’s been a Contributing Poetry Editor for Aquarius Press and a Poetry Editor for Human Equity through Art (where he’s now a board member). Crisler is an Associate Professor of English at IPFW. He can be contacted at www.poetcrisler.com.

December 14th, 2017 |

We’ve got another interview to share with y’all!

Anna Prushinskaya did with Evelyn Hollenshead of Pulp – Arts Around Ann Arbor about her book A Woman Is A Woman Until She Is A Mother, where she discussed her essay collection, motherhood, and how becoming a mother has changed her writing.

“…becoming a mom made me want to have more direct impact through my writing.”

Read Anna’s full interview about A Woman Is A Woman Until She Is A Mother here.

December 13th, 2017 |

More good news to share! Anna Prushinskaya, author of the recently-released MG Press title A Woman Is A Woman Until She Is A Mother, was interviewed by Juliet Escoria of Electric Lit!

“The title of the book is A Woman Is A Woman Until She Is A Mother in part because I was thinking about the categories of ‘woman’ that I have contended with in my life — motherhood being one of them — the broader implications of those categories, and about the power of a woman’s story.”

Check out the full interview on Electric Literature’s site.

December 12th, 2017 |

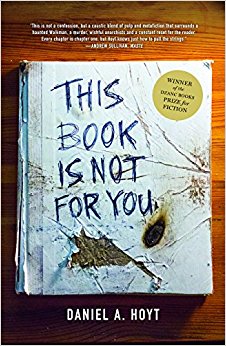

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Hoyt about his book This Book Is Not For You, experimental and fragmented writing, the literature of Rock and Roll, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Hoyt about his book This Book Is Not For You, experimental and fragmented writing, the literature of Rock and Roll, and more.

**

Carrie Dudewicz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Dan Hoyt: In 1988, I did a reverse Gatsby: I left the East Coast (Massachusetts) to go to the University of Missouri, where I completed a bachelor’s and stayed for a master’s. While at Mizzou and right after, I worked at both of the daily papers in Columbia, Missouri: The Daily Tribune and the J-School-run Missourian. I taught for a semester in Romania, and I lived in Binghamton, New York, for a year and a half or so, but since 1988, those are the exceptions, and I’ve mostly been a Midwesterner for my entire adult life: In the 1990s, I worked at two other Midwest newspapers (The Kansas City Star and The La Crosse Tribune), I got my PhD at the University of Kansas in the early oughts, I taught for six years at Baldwin-Wallace University in Ohio, and now I’m an associate professor at Kansas State University. I’ve got the golden handcuffs, so Manhattan, Kansas, is probably where I’ll spend the rest of my days. I’m the aesthetic and intellectual product of large public Midwestern Land Grant universities, and I’m so grateful for that. The Midwest made me a journalist. The Midwest made me a fiction writer. The Midwest made me a teacher. I don’t even say “cah” for “car” much anymore.

CD: You’ve spent much of your life in the Midwest. How does living in this region influence how and what you write?

DH: I write about the fucking messed-up and wonderful lives we have here, just like on the coasts. I write a lot of Midwest realism and Midwest magical realism, too, like my story where a man gets decapitated at a Burger King (the one right here in Manhattan, Kansas, actually) and then both halves of his body live on. A lot of people on the coasts don’t know that, that we have supernatural powers out here and that we live and bleed and we listen to punk rock in the basements of homes of very cool people and we make art and we wash out as purple politically and we give some of that blood to people in need and we plug into the internet and we drive faster than Springsteen and then we die here and we die a little bit every day, like everybody everywhere, and I don’t know what that really means, except our lives are messy and complex and not at all flat or boring or worth being fucking flown over, so I try to tell stories of those lives: of the 21st-century Midwesterners being caught looking silly on security cameras and trying to be rappers and trying to love without getting too fucking hurt. These are my people because I am these people. Neptune, the first-person narrator of This Book Is Not for You, has spent all but a couple of weeks of his life in Missouri and Kansas. He’s an anti-racist skinhead, and a punk, and a reader, and a writer, and he has a criminal past, and he’s an alcoholic, and he flails at love, and he tries, and he does stupid shit, and he’s haunted by ghosts, and he belongs to Lawrence, Kansas, and all of him belongs to this land. He belongs to Bloody Kansas. I don’t know — did I answer this one? Sort of maybe?

CD: This Book Is Not For You is a fascinating combination of multiple genres, told in a chain of “first” chapters. What inspired you to write such an experimental novel? How did that experience compare with writing more in more traditional forms?

DH: Oh, man, I’m going to answer the second question first, perhaps in a clever attempt to evade the first question. I started this book in 2003, when I lived in Lawrence, Kansas, and I didn’t finish it until 2014, and if it hadn’t been experimental and fragmented, I don’t think I could have finished it. I kept putting it down and picking it up and letting it sit for years, but because I was writing Neptune’s voice in these small bursts — in some ways I think of them like punk songs, short, fast, loud rude — I could summon him up somehow. He’s lived with me a long time. That’s how he thinks. That’s how he works. With more traditional forms, well, with short stories I tend to write in fragments too, but there’s a stronger process of sewing them together, of trying to hide the ragged seams. Neptune’s all ragged seams: they can show. Okay, now, that first question: I’m not sure what inspired me to write an experimental novel, except the book was born in this experimental town, in Lawrence, Kansas, a place that belonged to Native Americans and to abolitionists and to rock and rollers back in the day when it was going to be the next Seattle and to William Burroughs who lived there and to all the folks hanging out at the Replay Lounge. I wrote some of the first snippets on bar napkins, on the back of junk mail. I knew I wanted the voice to be punky, to challenge the reader. Man, that was a long time ago. I suppose something inspired me.

CD: Early reviewers say that the structure of the story, being told in only chapter ones, acts like a reset to the reader. Where did you get the idea to do this? Does this novel require that reader reset? If so, why?

DH: Yeah, I think there’s a really nice blurb that says there’s a reset for the reader on every page or chapter, but although I think that blurber is an incredibly astute judge of literature (Thank you, Andrew F. Sullivan! He was one of the judges of the Dzanc Fiction Prize, and because of his kindness and generosity — along with Kim Church and Carmiel Banasky—Neptune got to live a life in other readers’ heads. I’m so, so grateful to y’all), I don’t think the book resets. Neptune typically — eventually! — picks up where the last chapter left off, but, of course, the bigger point is that Neptune himself wants a reset: he doesn’t want to write the book or can’t write the book or can’t quite open up, but despite all this he still tries, and he tries to stop doing shitty things, and he tries to escape from his past, and each new chapter of course is something new, a fresh start. I think this idea came because, oh, hell, I think because it was fun?

CD: Similarly, was one experimental element more difficult to write than another? Was one more enjoyable?

DH: So many parts of it were enjoyable. It was superfun to bring in the ghost animals, and it was superfun to be snarky with the reader, and it was superfun to get all meta on the reader’s ass, and it was superfun to add the inside jokes and the noir elements and the Ghost Machine, which is a haunted Sony Walkman. Man, it was all fun! Which, I have to tell you, is so much easier to say and actually believe when the book is finished and printed!

CD: Are there specific experimental novels that inspired you? If so, which ones?

DH: Well, there are all those folks who did and are doing metafictional type stuff, and she hasn’t written a novel (at least that I now of), but I admire Kelly Link’s amazing prose and her sheer bad-ass bravado: Fuck yeah! Throw a zombie in! Apparently, too, there’s some sort of moment in House of Leaves that says “This book is not for you,” and the weird thing is, I’ve tried to read that book, and it just doesn’t kick into gear for me (that clutch just grinds), and I didn’t even know about the reference until after This Book Is Not for You was published, so I think the answer here is maybe? But, no, definitely not House of Leaves.

CD: As a professor at Kansas State University, how does your teaching influence your writing career and vice versa?

DH: Well, I love my students, and their work means a great deal to me, and because of that, during the school year, I spend a lot more time on their writing than on mine, but that’s kind of a shitty way to start here, so, well, shit, I get to be engaged in stories all the time, to think about narrative, to meet strange and wondrous characters that I would never create myself. I get to be inspired by my students, and I get to be energized by their hope and their possibilities. I try not to let my own writing influence my teaching beyond that I think people should try to do their damned best to write the richest versions of their own stories, the ones they want to tell, the ones they need to tell.

CD: You do a lot of teaching about literature and rock and roll. What drew you to this subject? How is rock and roll (generally) written about in fiction?

DH: I’ve been a rock and roll fan since my age was in single digits, but I probably got into rock and roll novels in my 20s. It’s a genre that allows for all kinds of cool interactions between form and meaning. My students seem to think that rock and roll literature is mainly about bands that fail, and, okay, they have a point there, but the literature of rock and roll does so many interesting things, like let us observe a really close friendship between a brother and sister (in Stone Arabia), or let us think about what being a “real” punk means (in A Visit from the Goon Squad). I’ve been putting together the Rock and Roll Reading at AWP (the fifth-annual will take place in Tampa), and it’s great, and everyone reads a piece that’s only as long as a song — just a few minutes — and let me tell you, the literature of rock and roll can do any damn thing it pleases. It’s up to the singer. Just sing loud, even if you can’t even sing.

CD: Is there a specific time of day you write best? If so, what is special about that time?

DH: I am a believer in writing pretty soon after you get up, so that the day doesn’t swallow you up along with your chance to write, and so that you can go through that day knowing you’ve written, that you’ve done it, and you, you my goddamn son, you do not have to feel guilty. But I teach and really care about it, and we have a 13-month-old, and the internet announces a fresh new catastrophe every second in 2017, so I’m fucking busy all the time, and accordingly I don’t have a special time to write, not really. I try to grab whatever I can. I’m 47 now, which feels ancient (thanks again, year 2017!), so all time feels special. I’ll take any hours you’ve got, minutes even.

CD: What’s next for you?

DH: Fiction-wise, I’m working on two novels, a realistic one set in Manhattan, Kansas, on Fake Patty’s Day (a day when students often begin drinking at 6 in the morning) and a more magical one set during the first 100 days or so of the Trump administration. I’m also working on a nonfiction book about the 1991 Fifth Down Game, when the officials made a mistake, and Colorado beat Missouri with an extra down on the final play of the game: It’s about the growth of big-time college football and mistakes and psychology and leadership. Life-wise, during the winter break, I’ll be roughhousing with Sey, our son, reading a stack of novels, playing some new vinyl, listening to bands at Manhattan’s Church of Swole, cooking some meals, taking walks, and calling my elected representatives: I’ll be yelping at them. I’ll be making New Year’s resolutions. I’ll be making up people who don’t exist, and, you know, they’ll feel alive.

**

Dan Hoyt’s debut novel, This Book Is Not for You, won the inaugural Dzanc Fiction Prize and was published on November 7, 2017. Dan’s first short story collection, Then We Saw the Flames, won the 2008 Juniper Prize for Fiction. Dan’s stories have appeared in The Sun, The Iowa Review, The Missouri Review, and other literary magazines. Dan teaches creative writing, mainly fiction, and lit classes, such as The Literature of Rock and Roll, at Kansas State University.

December 8th, 2017 |

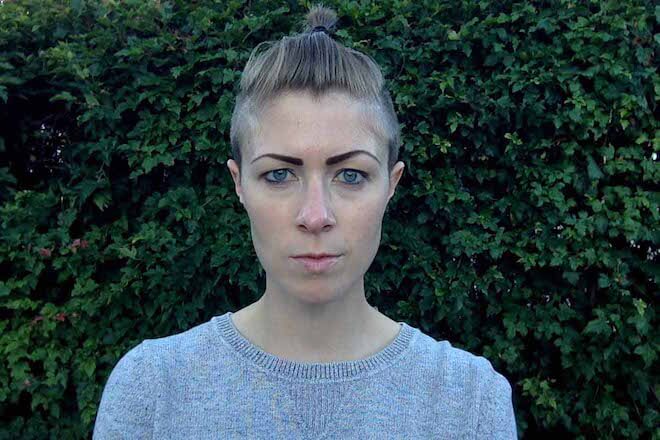

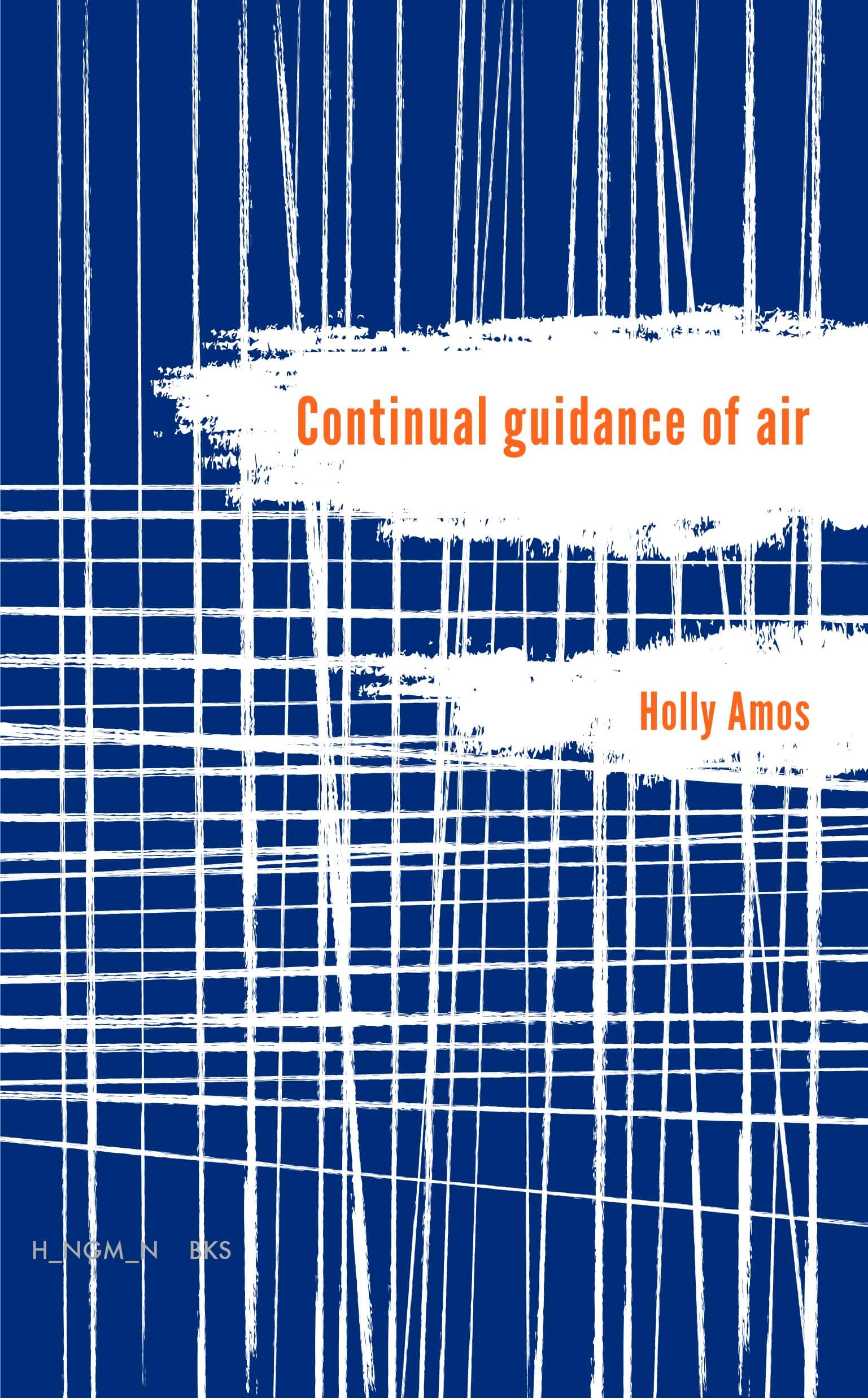

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Holly Amos about her poetry collection Continual Guidance of Air, her obsession with experience, finding her community, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Holly Amos about her poetry collection Continual Guidance of Air, her obsession with experience, finding her community, and more.

**

Kristina Perkins: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Holly Amos: Born and raised. I was going to say that I spent over 20 years there but then I realized I STILL live in the Midwest, though Chicago and rural Ohio are two very different places. When I think of the Midwest I think of my childhood—ditches, fields, small patches of trees. The middle of nowhere being everywhere. It’s a place that has deeply informed who I am (and who I am not). It’s a place I both reject and embrace. At some point I forced myself to stop saying “pop,” and I’ve been saying soda for so long now it was hard for me to remember that “pop” is what I used to call it. THAT was the Midwest marker I just couldn’t keep!

KP: How has your relationship to the Midwest influenced your writing?

HA: In the landscapes, the animals. In the colors. I think certainly in the wanderlust—in the yearning (I hate that word). Growing up where I did is probably part of the reason I read so much as a kid. I read Michael Crichton’s Sphere a lot. The idea that nobody had really seen a giant squid alive, that it lived that far down, was and still is comforting and exciting to me. I think it represents possibility. Not many people leave where I came from, and growing up, my brother and I walked across the field to play with our cousins. In some ways it was really lovely. I’ve just always wanted something back home couldn’t give me. Not that I’ve exactly found it.

KP: You work as an assistant editor for Poetry, a highly esteemed literary magazine. How has your job—and all the copy editing, proofreading, and fact-checking it entails—changed how you read and write poetry?

HA: Every time I use a tab I feel bad! They’re very unhelpful for typesetting in almost all cases. It’s also made me slow down and better try to recognize the immediate bias I’m bringing to a poem, whether it’s my mood, how much time I have or don’t, what else I’ve been reading lately. I think (and hope) I’ve become a more patient reader. There are a lot of poems I came to love while proofing an issue of the magazine that I didn’t love at first. So if I can tell I’m just not in the mood for something I check myself and come back to it later with a better head. I think that’s helpful for writing, too.

KP: In a previous interview, you’ve noted a rise in political, social-justice oriented poetry. Your own work in your debut full-length collection, Continual Guidance of Air, is similarly political, centering the lives of animals in the fight for animal and environmental rights. How do you understand the relationship between poetry and activism? How might poetry be wielded as a tool for political change?

HA: I think poetry can be an empathy conductor. It can also be a channel for information. I did a RHINO Poetry Forum recently (shoutout to RHINO!) where I talked about this and used a couple of examples, like the poem “I am not the most important forest you’ve been in” by Beyza Ozer. We are overloaded with headlines all the time, and at some point, I think most people just shut off. It’s easy to not read an article because you see the headline and you know what you’re getting into, so you sort of skim that information because it’s important, but you don’t necessarily engage with it. And sometimes that’s just self-preservation, you know? But poems, by nature, are things you have to engage with. If you don’t, there’s no point in reading. So poets have a rapt audience. It might be limited, sure, but it’s the best audience in the world for creating change, in my opinion. The poem by Beyza Ozer is not titled in a way that alerts you to the fact that it’s political, which I think broadens its reach, in a way. Like if someone is just DONE for the day, just wants to read a poem to sort of escape, they might come to this one. Except the very first line is the type of thing you read in the news. The rest of the poem is political in various ways and not political in various ways. By I think there are so many ways a poem can sneakily encourage openness and empathy in even the most DONE readers.

KP: Your poems in Continual Guidance of Air are rawly emotional and beautifully corporeal, navigating the embodied spaces between anger and pleasure, pain and hope. How do you understand the relationship between the body and the poem? How does your work capture this relationship?

HA: Thank you for this! I’ve been asked about the relationship between the body and the poem before and it’s really tough for me to answer. The way I think and the way I write are both definitely a product of my obsession with experience. Of how we experience. Of the fact that that it’s physical and mental—that the physical is filtered through our mind, that there are things we can do mentally to impact the physical experience and vice versa. While running my first marathon my feet started hurting a lot toward the end, and I decided to try and control it mentally, since pain is a mental message. In my head, I just started repeating “no pain no pain no pain” and after maybe 30 seconds or a minute it stopped. (This is part of one of the poems in my book, “Specific Motion.”) I’m obsessed with this. I’m obsessed with experience as something we craft, whether directly or indirectly, for ourselves or for other selves, and as something we respond and react to. I mean what else is there? In writing a poem, we are deliberately crafting experience and responding to it simultaneously. I think writing alters the origin experience(s), and also creates a new experience. It’s a blossoming effect. That in and of itself is an incredible thing, and an exciting thing.

And to go back to your question, the body is very much part of that. Without the body there might be a type of experience (the soul—or being part of the universe—just atoms, just matter—that’s still a type of experience, in my mind—and it might be something we feel or sense as beings—I don’t know)—but as long as I’m a bodied individual my experience is always going to be directed through that body, until it isn’t. So that feels really necessary to me in writing a poem, because ultimately I am trying to get somewhere deeper or more illuminated.

It’s also something I think about all the time in terms of animal rights. What does it feel like to be a chicken in a battery cage, what does it feel like to be a cow who’s just given birth and had her baby physically removed from her hours later so that a person can drink her milk. I’m talking about empathy, but for me empathy is very much tied to mentally trying to imagine a bodily experience. Like a chicken in a battery cage—I know what it feels like to feel cramped on a train. How awful that can be. How anxiety ridden and just physically uncomfortable. And then thinking about my entire life being that experience only. It’s devastating.

So what I’m also arguing is that empathy is something we practice—it’s not something we have. And the more we practice it the easier it is. Which can be uncomfortable, just like running, or yoga, but its worthy of the discomfort. And eventually we find ways to cope with the discomfort, ways to get beyond it while not foregoing the practice. Like foregoing cheese. It was uncomfortable at first. I craved it for a while and just had to sit with those cravings. But eventually my reaction, my response to not eating cheese changed and I no longer felt discomfort. Sorry for all that, but you know that old saying, “If you give a vegan a platform, they’ll take it.…”

KP: Relationships—between humans and animals, between humans and humans—form the backbone of your poetry in Continual Guidance of Air. Previously, you have offered a series of “Notes for a Young Poet,” writing: “Find your people / (I’m your people) and hold them all together. A small but / powerful porch of humanness.” How has finding your community—be it among co-workers at Poetry, former peers from your courses, or the animals in your home—influenced your identity as a writer?

HA: Oh my god well it’s everything. The first time I really, really felt like I found my community was in grad school. I know I was very lucky to have the people with me that I had. And then I started going to AWP and to readings and was like, “Wait there are more people like this??!!” But up until that point I’d been working at a company that bought real estate tax liens. It wasn’t something I wanted to keep doing, but I had always imagined that I’d keep one foot in the “real world” and one foot in the “poetry world.” When grad school was ending I realized I didn’t want to lose the community I’d found, so I quit that job and decided to apply to anything arts-related. Interacting with poets and poetry lovers at the Poetry Foundation, through The Dollhouse (a reading series I co-curated), and just through being a writer in the world, allowed me to no longer see the “real world” and the “poetry world” as separate. I think that’s a big deal. I also think it influences my identity as a writer. We are all soooo affected by one another, on micro and macro levels. I don’t think everyone wants to feel that all the time, but I think that’s a really important thing to honor AND to wrestle with, and I think doing so is crucial to social change.

KP: Describe your ideal writing environment. What (or, perhaps, who) is around you? What are you listening to? What utensils are you using? What are you looking at?

HA: I actually don’t like the idea of an ideal writing environment. I am very wary of routine when it comes to writing, wary of developing specific habits. I just worry about stasis and stagnation and I also think it’s important to cultivate openness. So I have a tendency to write lots of places. On a scrap of paper on the train to work, in my phone when I’m outside with the boys who have become ever-present in my writing (they’re dogs!), or on my laptop during a quick break at work because I just read something that did that thing where you immediately need to move with it.

KP: Who do you write for?

HA: Everyone, I hope.

KP: What’s next for you?

HA: I’ve been writing new poems that I think/hope are engaged in a broader sense. But I also have been thinking about non-poetry writing a lot and just started an essay about something that is very uncomfortable for me to talk/write about. It’s something that consumes me in many ways, and I’m hopeful it will be cathartic but also helpful to other people. Really, I’ve written barely anything so far because it takes a lot to get into it, but I’m excited about it, which is something!

**

Holly Amos is an animal rights advocate and vegan. She is the author of the full-length poetry collection Continual Guidance of Air as well as the chapbook This Is a Flood. Currently living in Chicago, she is the assistant editor of Poetry and a poetry editor for Pinwheel; she also co-curated the Dollhouse Reading Series.

December 7th, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Tatiana Ryckman about her book I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do), translating longing to written word, shorter-length publications, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Tatiana Ryckman about her book I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do), translating longing to written word, shorter-length publications, and more.

**

Marisa Frey: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Tatiana Ryckman: I was born in Cleveland and went to school in central Ohio until college, when I moved to Nebraska. I’ve heard from impassioned Minnesotan and Michigander friends that neither of “my” states are the Midwest, but I politely disagree. The longer I spend in Texas, the more obvious it becomes that I’m from someplace else.

MF: Readers don’t know much about the identity of the characters in I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do)—they are nameless and genderless. What advantages and disadvantages did this pose while you were writing?

TR: The absence of names and genders happened surprisingly organically. I wrote section 1 in a single sitting and didn’t realize it would be part of a longer work. It seemed natural that a narrator would not talk about their name or their gender, nor the name/gender of the person being addressed. That section is really an admission of embarrassing longing across a great distance. The real struggle was maintaining this throughout the entire book when the characters were in the same place. As you mentioned, the reader never really gets a sense of what these characters look like. A benefit, or at least what I hoped would happen, is that readers would begin to see themselves as the narrator, and they would know exactly for whom they longed, or for whom they had once longed so tenaciously.

MF: I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do) is deeply confessional, probing at the innermost reasons for longing and loneliness. What was it like to write it?

TR: I love this question, though I don’t particularly love answering it. Writing this felt embarrassing, and shameful, and very depressing. I am not the narrator, but I (and I assume most people) have longed for someone far away, or who feels far away, and I found myself digging up and mining those old feelings, as well as creating/imagining new ones. How strange to make oneself obsessed with someone who doesn’t exist! And having that realization while writing was what ultimately led the narrator to understand that even if there was a real, breathing person on the other side of their obsession, the person they were longing for was really an object of their own creation.

MF: Do you consider I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do) a love story?

TR: Kurt Vonnegut says that all stories are love stories. Certainly by those standards it is.

MF: In addition to I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do), a novella, you are the author of two chapbooks, one flash-fiction and one flash-nonfiction. What appeals to you about these shorter-length publications?

TR: Lately I’ve heard comparisons to Twitter stories and about diminished attention spans, but I don’t find that to be my inspiration or motivation. I like them physically. They’re easy to stick in a purse or a pocket. My reaction when I see a very thick book is generally, “This must not have been well-edited.” Naturally there are many times when I’m wrong, and I am glad to be. Yet there’s something really wonderful about letting a single moment stand in for significantly more. One can dip into that world and emerge slightly different. There’s something poetic about it—as in poets do this all the time. And I like making words work a little harder, to earn their keep.

MF: You released a four-part video trailer for I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do). What was the inspiration for that? Can we expect more multimedia projects from you?

TR: I was incredibly fortunate to have a filmmaker friend, Robert Moncrieff, offer to make those trailers for me. He did a beautiful job. I have recently gotten excited about printmaking, so I do have hopes of mixing mediums in the future, though I’m not yet sure how that will happen or when or in what capacity.

MF: What are some advantages and disadvantages of writing books in the digital age?

TR: The advantage is, in theory, increased exposure. The inverse, then, is the disadvantage—the sheer glut of information potential readers are exposed to. Why should they read this book?

MF: What’s your ideal setting to write in?

TR: Physically, anywhere. Mentally, it seems to come best in a liminal space. While traveling, or moving from one task to the next. Long road trips or while switching between books. There’s something about disparate ideas or actions or places rubbing up against each other that seems to get me going.

MF: What are you reading right now?

TR: I’m drifting through many books right now. Very slowly. I’ve been revisiting To the Castle and Back by Václav Havel and have just started The Power Broker by Robert Caro. I’m very excited about Caca Dolce, by Chelsea Martin and Circadian, by Chelsey Clammer. And I think it’s just good practice to always have James Tate and Thomas Paine on hand. I’ve had Memoir of the Hawk (Tate) and Paine’s collected essays by my bed for a few months.

MF: What’s next for you?

TR: This is the question I’ve been fearing since the book came out last month. I haven’t started anything new. I have an old novella manuscript and a short play that I’m thinking about dusting off and working on. Also a few essays. I’m just waiting for something to catch.

**

Tatiana Ryckman was born in Cleveland, Ohio. She is the author of I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do) as well as two chapbooks of prose. Tatiana is the editor of Awst Press and has been an artist in residence at Yaddo and Arthub. More at Tatianaryckman.com.

December 1st, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with co-authors Anders Carlson-Wee and Kai Carlson-Wee about their collection Mercy Songs, hitchhiking across the Midwest, exploring new mediums of poetry, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with co-authors Anders Carlson-Wee and Kai Carlson-Wee about their collection Mercy Songs, hitchhiking across the Midwest, exploring new mediums of poetry, and more.

**

Meghan Chou: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Anders Carlson-Wee: We grew up in Minnesota. Our parents are both Lutheran pastors and served congregations in Northfield, Fargo-Moorhead, and Minneapolis. Our great-grandparents were part of a wave of immigrants from Norway who settled in Minnesota around 1900. When I bicycled across the country twice in the 2000s, I had the most illuminating, heartfelt, and layered conversations with strangers in the Midwestern states (although the craziest stories from those travels came out of the South). I moved back to Minneapolis two years ago, after being away for thirteen years. I would say much of who I am is Midwestern, and that influences how I think, act, and write.

Kai Carlson-Wee: Anders and I grew up in a small town in southern Minnesota, called Northfield. We lived a block from a cereal factory and a train yard and spent the bulk of our time roaming around town on our bikes. It was a very American childhood. We raced go-carts down the street and stuff like that. When we got older our family moved up to Fargo, North Dakota, where we went to high school. Fargo was more blue collar, more prairie, but still very Midwestern. You wouldn’t exactly call it a destination city, it was more of a place people got lost in or stranded in and somehow failed to leave. When I graduated from high school I moved out to California to be a professional rollerblader. I felt more comfortable on the coast, more myself, but I kept bouncing back and forth. I went to college in Minnesota, moved to Portland, moved back. I think my spirit belongs to the stuff out west, but my heart is stubbornly Midwestern.

MC: The theme of brotherhood is strong in many of the poems in Mercy Songs. How do you, as brothers, inspire each other and how did growing up in the Midwest influence your relationship with one another?

ACW: While Kai and I were growing up in northern Minnesota we were serious rollerbladers, and skated semi-professionally for a while. Together we designed and built a skate park in our garage, using materials we stole from the half-finished homes on our block. The garage skate park gave us a place to skate every day during Fargo-Moorhead’s subzero winter, although it wasn’t much warmer in there. When you share an interest with a brother, you’ve got a partner in crime—someone to commiserate with, someone to plan with. And you have someone keeping you in check. On school nights, we’d skate for up to five hours, often going back out into the cold after dinner for more. I don’t think either of us would have stayed as focused without the other one. As for being from the Midwest, our landlocked small-town life didn’t offer many options—for entertainment, for friends, for ideas—and I think that helped Kai and I form an extra strong bond. It also shaped our imaginations. I think of the Midwest as having a deeply physical imagination; this takes form in everything from the protestant work ethic, to the suspicion of things that are too far “out there,” to a trust in, and love for, the things of the earth: the things you can see and touch and smell and hear and feel. This isn’t all positive. Or healthy. But I think it’s had a profound impact on how Kai and I think, on how we relate to each other, and on how we write.

KCW: Well, we grew up skating together, and when you’re a skater, especially a rollerblader, you get a lot of adults trying to tell you to quit. Cops, security guards, teachers, parents, even your friends. You start to develop an anti-authority thing and you become pretty insular and self-reliant. When we first moved to Fargo, Anders and I didn’t have any friends so we turned to each other for support. We spent hours and hours skating in our garage learning tricks on the ramps and rails we built. When we went street skating we had all these confrontations with authority figures and random people who wanted to mess with us and we developed a bond around that. We had to watch out for each other. I don’t know if the Midwest made it any different, but there’s a way in which the Midwest is easily dismissed by the larger, more cosmopolitan zones in this country. I think Anders and I both have a chip on our shoulder about systems or individuals who assume hierarchical positions of power. We tend to empathize with underdogs and outcasts, and the place we grew up in probably informed that.

MC: In Mercy Songs, a collection the two of you co-wrote, the poems alternate voices and play off of one another like a call and response. What are the benefits and difficulties of co-writing a collection of poems?

ACW: As brothers, we’ve been having an ongoing conversation our whole lives; Mercy Songs is a natural extension of that conversation, but the book makes it accessible to an audience, which allows the world to interpret and sculpt our voices for its own needs. That’s scary, but also liberating. I think it lets us move forward, and let go, in a sense. It’s also been very cool to be able to read together from the book, enacting the call-and-response format for a live audience.

KCW: The poems in Mercy Songs were written independently of each other, but they were written about similar experiences, so the connections between them are mostly accidental. It’s not like we sat down and said, let’s write a chapbook about traveling together, it was more like we noticed there were similar themes in our work, characters, ideas, landscapes, etc., and the poems already had resonance. The project of putting the book together was more like shuffling cards, so the construction was actually pretty easy. I think the danger of doing a project like this is that the poems might feel out-of-sync, either too similar, or too different, and our goal was to arrange things in a way that felt harmonic and had some sort of narrative flow. Not sure if we pulled it off, but that was the idea.

MC: Many of the poems in Mercy Songs revolve around your adventures train-hopping cross-country together. There are references to “bulls” (the train security guards) and descriptions of the intense heat. How did these trips change your perception of the Midwest and the landscapes you write about?

ACW: Train-hopping is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. It leaves you utterly submitted to the world—the elements, the weather, the unceasing pulse forward—and reduces you to your basic desires and needs: water, food, shade, sleep, companionship. It cracks your skin, bloodshots your eyes, parches your throat, rattles your spine, and steals your mind away to the edge of reason and sanity and self. It’s an overwhelming tactile experience. And it’s not uncommon to experience hallucinations, waking dreams, spatial disorientation. Every time I’ve hopped trains I’ve heard voices. I don’t mean I thought God was talking to me; I mean you’re so worried about getting caught, so shaken by the train’s heaves and clinks and hisses, so strained by the long nights in the alternating dark and sharp light of railroad yards, so worn out from the waiting and hiding and the nothing happening but jolts and flashes and speed, that you start needing the stimulus around you to mean something—you start needing the world to pertain to you. I think this is the intrinsic primitive impulse that births religion, storytelling, and art. We need the world to pertain to us, and for us to pertain to it. We crave this. A sense of order. Of cause and effect and consequence. For me, train-hopping has been a way to experience that need, sharply. But all art and religion deals with this need. Poetry offers acute access to it. As for a specific location, such as the Midwest, train-hopping gives you the experience of passing through a place—a rush of time and perspective, which alters what remains the same, as your position changes. And like I was describing, it also takes you into a condition where you can peel back the veil, slightly and momentarily, like a good poem can do.

KCW: I don’t think it changed anything, exactly, but putting the book together made me think about the particular culture we’re trying to illuminate. Ever since I was young, I’ve been interested in the gothic side of the Midwest, the dark and weird shit. People have explored this element in the south, but they haven’t really nailed it down in the Midwest. When you think about literary representation, you have the family dramas of Willa Cather, stuff like Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom, the quirkiness of Garrison Keilor, the lonely isolationism in Stoner and Winesburg Ohio, the natural beauty and subtlety of Robert Bly, but none of these versions line up with the weird idiosyncratic violence and surrealism I experienced when I was younger. Films like Fargo by the Coen Brothers and Badlands by Terrence Malick are more invested in this quality. Music albums like Separation Sunday by The Hold Steady and Rooster by Charlie Parr are also in this direction. Traveling around the country helped me see different versions of American weirdness, but there’s a particular quality in the Midwest that I’m interested in writing about. It has to do with spiritual poverty and the way people use pleasantry and morality to justify violence and to combat an existential dread of the land.

MC: Your joint short film, Riding the Highline—which won a Special Jury Prize at the Napa Valley Film Festival, among other awards—incorporates visuals with recitations of poetry as you ride from Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Wenatchee, Washington. What did you learn from documenting this trip about the connection between poetry and film as well as the power of combining the two?

ACW: Riding the Highline allowed us to frame two lyric poems with the larger narrative context of the film’s story, which seems to have resonated with a wide audience. And it continues to allow us to sneak poetry into a huge range of venues: high school auditoriums, dive bars, art exhibitions, college classrooms, film festivals, hobo gatherings, art crawls, and lots of people’s living rooms (via the internet). We’ve had people come up to us and quote lines from our poems, often saying something like “I’ve never read much poetry, but now I will.”

KCW: Poetry and film both operate on a linear timeline. They’re both potent, powerful mediums, and can convey a lot of feeling in a small amount of space. Film is more superficial, but it creates more of a total atmosphere. Poetry is generally deeper, more internal, but also more subtle in the way it hits your emotions. If the two are combined in a natural, harmonic way, the results can be powerful. When we’ve screened Riding the Highline at film festivals, people always ask why we wanted to combine the two mediums, what genre we’re trying to invent. But I don’t know, to me it just seems like an obvious thing to do. I get a little tired of reading poems in books. Black and white, print on page. I love books, but I don’t see why writers aren’t expanding their ideas of what poetry can become. When you look at what’s happening with something like Instagram poetry, you can see there’s a real interest there, an appetite. Rather than laughing at how awful it is, I think we should take some notes and start seeing these forms as a sign of health, of new directions in poetry.

MC: What is the most memorable trip the two of you have taken together and how did it affect your life philosophies?

ACW: One time Kai and I hitchhiked from Minneapolis to Chicago by way of Wisconsin, and we had the most insane rides. Every person that picked us up was more unhinged than the one before. We got a ride from a young man who’d had a heart attack from doing too much coke on his eighteenth birthday. We got a ride from a single mom and her five-year-old son, who sat beside us eating a Happy Meal; she kept saying if we were any bigger she wouldn’t have picked us up. We got a ride from a man with fresh wounds on his face, the result of fighting his friend when his friend caught him stealing his four Labrador puppies; he said he stole the puppies because his friend was letting them die of heatstroke in a backyard cage, and he picked us up because he needed someone to give the puppies water; they sat on our laps and drank from a sour cream container (a much, much, much longer story). That trip affected my life philosophy about Wisconsin.

KCW: My favorite trip with Anders was a hitchhiking trip we took back in 2006. I had just graduated from college, Anders had recently finished high school, and our plan was to hitchhike from Minneapolis to Chicago with no real agenda. I think I had just broken up with a girlfriend and was feeling slightly nihilistic about everything and we just wanted to get on the road and take things as they came. Somehow, every ride we caught was extremely weird, and we ended up riding with this guy named Rick who was wildly spun out on meth. He had six little St. Bernard puppies in the car and he was talking a mile-a-minute and ranting conspiracy theories about George W. Bush. We honestly thought he was going to kill us, but then he didn’t, and everything turned out okay. We ended up at a Phil Lesh concert and then accidentally attended the gay Olympic games in Chicago, where everyone thought we were a couple. The whole trip took place in a week but it seemed like an endless surreal dream. Still one of the most memorable trips we’ve taken.

MC: After returning from these trips of solitude and excitement, how do each of you find places and time to write in your daily lives?

ACW: I live in Minneapolis and write poetry full-time. I dumpster dive for most of my food and live a humble life. I piece together an income from touring, publishing, teaching, awards, grants, etc., but I wouldn’t be able to sustain this lifestyle for very long without the generous fellowships I’ve received from the NEA, Vanderbilt University, and the McKnight Foundation. Those three fellowships have paid for the lion’s share of my life for the last five years, and I am forever grateful.

KCW: Almost everything I write is autobiographical and based on experience, so I need these periods of adventure and wandering around. I need weeks of doing things randomly, without agendas. If I’m being too responsible with my life, my poetry gets fake. It’s not that it gets bad exactly, it just gets repetitive and boring and starts to parody itself. I never want to get to the point where I’m writing poetry for the sake of writing poetry, either because I’ve committed myself to a poetry “career” or because I’ve established too much of my identity around previous work. I want my poems to keep springing from inspiration and impulse, rather than expectation. Right now, I’m lucky enough to be on an academic schedule, so I can travel and write during the summers. During the school year I have three days a week to do whatever I want, and I usually spend that time at coffee shops, working on poems, reading, taking photos around the city. This makes me a difficult person to date or be friends with, but I don’t really mind. I think at the end of my life I’ll regret not having more friends, but I’ll regret less the poems I’ve written, the time I spent alone.

MC: What’s next for each of you?

ACW: I’m finishing my first full-length poetry collection and spending the summer in Guadalajara. Starting in the fall, I’ll be touring heavily. If you want me to tour through your town/school, email me: anderscarlsonwee@gmail.com

KCW: My first full-length collection of poems, RAIL, is coming out with BOA Editions in Spring 2018. I’ve been working on the cover and have started production on a series of short films, which I’m hoping to release with the book. The idea is basically to make a visual version of the poems, with video, audio, photographs, etc. I want it to be a stand-alone piece, rather than a series of music videos. Hopefully it doesn’t suck.

**

Anders Carlson-Wee is a 2015 NEA Creative Writing Fellow and the author of Dynamite, winner of the 2015 Frost Place Chapbook Prize. His work has appeared in Ploughshares, New England Review, AGNI, Poetry Daily, The Iowa Review, Best New Poets, The Best American Nonrequired Reading, and Narrative Magazine, which featured him on its “30 BELOW 30” list of young writers to watch. Winner of Ninth Letter’s Poetry Award, Blue Mesa Review’s Poetry Prize, and New Delta Review’s Editors’ Choice Prize, he was runner-up for the 2016 Discovery/Boston Review Poetry Prize. His work has been translated into Chinese. He lives in Minneapolis, where he serves as a McKnight Foundation Creative Writing Fellow.

Kai Carlson-Wee is the author of RAIL (BOA Editions, 2018). He has received fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and his work appears in Ploughshares, Best New Poets, New England Review, Gulf Coast, and The Missouri Review, which awarded him the 2013 Editor’s Prize. His photography has been featured in Narrative Magazine and his poetry film, Riding the Highline, received jury awards at the 2015 Napa Valley Film Festival and the 2016 Arizona International Film Festival. A former Wallace Stegner Fellow, he lives in San Francisco and is a lecturer at Stanford University.

November 30th, 2017 |

We’re thrilled to share the first of what we’re sure will be many stellar reviews and interviews for A Woman Is A Woman Until She Is A Mother by Anna Prushinskaya!

The folks over at Michigan Quarterly Review interviewed Prushinskaya, while The Coil was kind enough to review the newest MG Press title, and here’s what they had to say:

“Either that one of the one they head the review with Prushinskaya’s essays are an intriguing compilation of a woman’s flight through child bearing, told with care, pain, and freshness.” — Surmayi Khatana, The Coil

Read the full review on The Coil‘s website.

Meanwhile, in an interview with Cameron Finch from Michigan Quarterly Review, Prushinskaya discussed her collection, being born into a different mother, identity and more.

As Prushinskaya explains in the interview, “the title of the book is ‘a woman is a woman until she is a mother’ in part to reflect that our experiences are our own, are varied, though sometimes others might try to tell us otherwise by placing us into categories like ‘woman’ or ‘mother’ or etc.”

Read the full interview at Michigan Quarterly Review.

For more information about A Woman Is A Woman Until She Is A Mother, and to purchase your copy, see the book page on our site.

November 29th, 2017 |

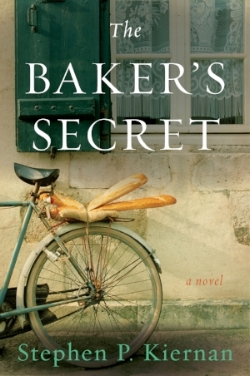

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Stephen Kiernan about his book The Baker’s Secret, researching World War II, finding lightness in tragedy, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Stephen Kiernan about his book The Baker’s Secret, researching World War II, finding lightness in tragedy, and more.

**

Meghan Chou: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Stephen Kiernan: My connection to the Midwest is that I am an American. We may not act like it these days, but we are still part of a larger whole.

Also I lived in Iowa for several years in the 1980s. For a while I taught in the Artists in the Schools program, which introduced me to people and places all over the state. I loved it there.

MC: The Baker’s Secret follows a young baker, Emma, in the small seaside French village of Vergers the day before D-Day. Why did you decide to focus the novel on the course of only one day? What are the advantages and disadvantages of such a condensed timeline?

SK: The job of the novelist, to my mind, is to tell the richest possible story in the shortest possible duration. My effort was to attempt to capture all the suffering and triumph, oppression and cunning, of an occupied people not through a portrayal of the years they were forced to live that way, but in the course of a single exemplary day. The fact that the occupying army is uncovering Emma’s network throughout the day, and that the reader knows an invasion is coming but the characters do not—to me these are potent sources of suspense.

Think of it this way: If the story were even one day longer, wouldn’t it be cumbersome and slow?

MC: Every day, Emma decides to sneak the villagers two loaves of bread made from the flour rations meant for German occupying troops. How does this small act of rebellion from an ordinary woman sustain hope for the community that help will eventually come?

SK: “There are no great deeds. There are only small deeds done with great love.” — Mother Theresa

MC: Emma learns her craft from Ezra Kuchen. However, since Ezra is Jewish, the Nazis arrive to take him away at gunpoint. How does Emma’s relationship with her mentor, Ezra, and the Germans’ treatment of him influence her decision to rebel?

SK: Emma begins the novel as powerless as a person in that time could be: female, young, unarmed, unparented, her fiance conscripted, her mentor Uncle Ezra taken away, a grandmother with dementia her endless responsibility. She is the least likely heroine. Yet it turns out she has learned generosity from Uncle Ezra. She has learned kindness from the vulnerability of her fellow villagers. She has learned stubbornness from that same difficult grandmother. Her entire life has been preparation for the role she assumes in her village.