Interview: Ben Stroud

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jamie Monville talked with author Ben Stroud about writing authentically, exile, Wes Anderson, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jamie Monville talked with author Ben Stroud about writing authentically, exile, Wes Anderson, and more.

**

Jamie Monville: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Ben Stroud: I moved here in 2002 to go to grad school at the University of Michigan for a PhD in English. Except for two years, I’ve been here ever since.

JM: You grew up in Texas, but have spent the past several years settled in the Midwest either in Michigan or Ohio. How does living in two completely different climates and places affect your writing? Do you see any similarities between Texas and the Midwest?

BS: I think the difference between where I live now and where I grew up gives me, perhaps, a better perspective on where I came from. Or maybe better—who knows? But that separation, that “exile,” can be important for writers. The longer I’ve been away, the more I’ve been able to look at Texas as both an outsider and an insider. Likewise, I feel like being an outsider to the Midwest has given me a way to appreciate the Midwest. I like having seasons! OK, it’s early March of the longest winter ever as I type this, but I still hold to that. Similarities? Hmm. Hard to say—maybe I’m too cowed by this winter. But I find it hard to speak in broad categories. One of the things I’ve resisted is thinking of Texan-ness (or Midwesterness) in terms of the stereotypes people often use. Not for any noble cause, but they often break down when you look up close. Which Texas, the Texas of my small town, the Texas of Dallas, the Texas of Austin, the Texas of El Paso? Or the Midwest, which is so rich in variety: Toledo is so hugely different from Ann Arbor. And, say, Minnesota? Minnesota is almost another planet. I guess the only basic similarity I can commit to is that they are both places full of people, with all our contradictions and differences and samenesses.

JM: You received a BA in English and History at the University of Texas at Austin and an MFA in Fiction as well as a PhD in Twentieth-Century American Literature from the University of Michigan. What do you think that your knowledge of history and American Literature specifically brings to the stories that you write?

BS: Well, with history: I’ve always been interested in history. My father is a history teacher at Kilgore College and so I grew up with it. And for me, too, my interests in history have always been wide-ranging: in college I was taking classes on Anglo-Saxon Britain, on Rome, on the Ottoman Empire, etc. That same wide-ranging interest leads me to the stories I write. I’d like to say that my PhD has helped me just by giving me so much time to read, and the opportunity to read through so many periods of literature. I’m one who argues for the classics. And I think in some of the stories I’ve written I’ve been reaching back for older approaches to story, to narration, to voice, to form. I’m attracted to the Victorian moment in many ways—before there was any hard divide made between “genre” and “literary.”

BS: Well, with history: I’ve always been interested in history. My father is a history teacher at Kilgore College and so I grew up with it. And for me, too, my interests in history have always been wide-ranging: in college I was taking classes on Anglo-Saxon Britain, on Rome, on the Ottoman Empire, etc. That same wide-ranging interest leads me to the stories I write. I’d like to say that my PhD has helped me just by giving me so much time to read, and the opportunity to read through so many periods of literature. I’m one who argues for the classics. And I think in some of the stories I’ve written I’ve been reaching back for older approaches to story, to narration, to voice, to form. I’m attracted to the Victorian moment in many ways—before there was any hard divide made between “genre” and “literary.”

JM: In past interviews you have indicated that something that you think a lot about is how much research you need to write authentically from a historical perspective. What are your recent thoughts regarding this question? And how do you go about your own story telling in order strike a balance between authenticity and letting the story dictate its own fate?

BS: I’m constantly rethinking my approach to research, and trying to find what is the best approach for a given story. When Edward P. Jones gave a reading at Michigan, I asked him about his research process for The Known World and he said he didn’t end up doing much research—that he found it got in the way. He knew the basic facts that form the novel (the instance of black people owning slaves in the antebellum South) and invented everything from that: a fictional county, fictional people, etc. In many of my stories I’ve spent a lot of time doing research, but for a recent story—”Jessup,” in the current issue of Zoetrope—I followed Jones’s method. I got the notion of the story from something I’d heard while visiting Mammoth Cave. I thought at first I should do tons of research. But then I thought: make it a fictional cave and focus on the characters, the dialog, and see how it develops.

JM: You have also indicated that world-building is an aspect that you focus a lot on. How do you know what kind of world is appropriate for what story? Do you have a particular idea in mind when you decide to create a world, or does the world come before and shape the story that results?

BS: Sometimes, but not always, I’m drawn to a story because of the world it is set in. This was true for “Byzantium” (7th-century Byzantine empire) and “Traitor of Zion” (a religious commune in the far north of Lake Michigan, based on a real such community that existed on Beaver Island). I’m interested in exploring something in that moment, and so part of the process of crafting the story is finding the character who will take us there. I don’t know that there’s a particular idea. Usually it’s a fascination. Writing the story is the way I figure that fascination out.

JM: What’s one thing you wished you’d known when you first began writing?

BS: When I was in college, Wes Anderson came to talk to us as he was plugging for Rushmore—this was way back before he was “Wes Anderson.” Only a few people showed up. (This Q and A was held off campus, outside his small tour bus, which was parked in a vacant lot—and Jason Schwartzman was there, too.) At the time I planned to be a film major. I asked Wes Anderson what advice he had for young film majors. He thought a moment and then said, “None.” At the time I thought he was a jerk. Only later did I learn that he was never a film major, so perhaps he wasn’t that invested in the question. And only later still did I think there was a lot of truth to his advice. There’s not really any magic bit of advice to be given for people who want to create art, whether it be film or writing or whatever. I was lucky to have good teachers who let me know that being a writer meant lots of work and lots of rejection. That was one good thing to know.

I’m a teacher, so I’m very invested in the notion that there are real things that we can tell beginning writers that will help them. And I believe that. But I also know that being a writer (or anything else) is a complicated, rough journey that each of us experiences in our own way, and so in a way the best thing to know is that there is no magic advice that will fix it for you.

JM: Which writer has most influenced your style?

BS: There isn’t any one writer I could name. I remember an early Richard Ford period. Later, Steven Millhauser, Jim Shepard, Lily Tuck (News from Paraguay was one of the first historical novels I read that blew me away), Hilary Mantel. I could name lots and lots of others—I try to read widely and it all goes in, it’s all fodder for thinking through my own work. For instance, I love Mary Gaitskill’s writing. Is my writing anything like hers? Probably not. But there are things in her work I keep thinking about—and I’m sure it shows up in my own work in some way, even if it’s hard to identify. That’s just one instance—there are a lot of other writers I feel that way about.

**

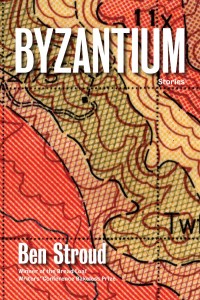

Ben Stroud is the author of the story collection Byzantium (Graywolf), which won the 2013 Story Prize Spotlight Award and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference Bakeless Fiction Prize, and was named a Best Book of the Year by the Kansas City Star, Best Summer Book by the Chicago Tribune and Publisher’s Weekly, and a Best Book of the Month by Amazon. Ben’s stories have appeared in Harper’s, Zoetrope, and One Story, among other places, and have been anthologized in New Stories from the South and Best American Mystery Stories. He is the recipient of a 2014 Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award, has received fellowships from Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony, and has taught literature and creative writing at universities in the US and Germany. Currently, Ben is Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Toledo.