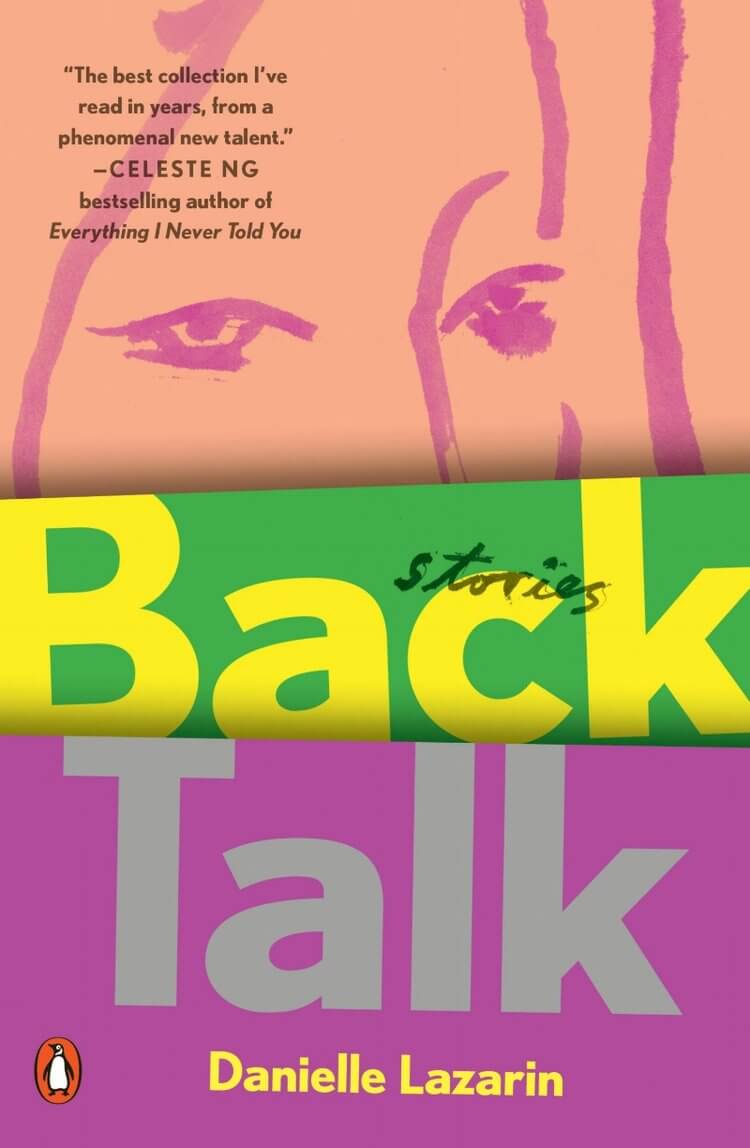

Interview: Danielle Lazarin

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Danielle Lazarin about her book Back Talk, the relationships between intimacy and femininity, motherhood, experiencing the Midwest as a New Yorker, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Danielle Lazarin about her book Back Talk, the relationships between intimacy and femininity, motherhood, experiencing the Midwest as a New Yorker, and more.

**

Carrie Dudewicz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Danielle Lazarin: I spent most of my advanced schooling years in the Midwest. My undergrad degree (in creative writing) was at Oberlin, in Ohio, and my MFA at the University of Michigan. I remained in Michigan for a few years afterward before moving back east. When I think Midwest, I think walking to a workshop through some amount of snow, in the most pleasantly nostalgic way.

CD: You spent a lot of time in the Midwest, but you’re from and currently live in New York. What are some of the differences you see between these two places? How did/does each place affect your writing differently?

DL: I have affection for much of the Midwest but wouldn’t say I feel at home there. Being an outsider bred curiosity about the kinds of things we take for granted about the places we are from: the landscape, and childhoods, and expectations, the way a day is lived. In Michigan specifically, I lived a more suburban life than I had in cities I’d previously settled in. The lack of population density — that I could be so easily isolated — did not sit well with me, and I felt more disconnected in the Midwest than I’ve felt elsewhere. I suspect, looking back, that those feelings were good for various stories that touched on themes of loneliness and longing for a different kind of life.

When I moved back to New York after 15 years living elsewhere, I was surprised at how deeply I felt connected to earlier versions of myself, as I was encountering a long-lost friend. Some of it was the basic sense of being home, of being comfortable in a way I never was when I lived in the Midwest or California. But some of it was quite literal, as I was retreading of the ground of my teenage life but in a different skin: as a mother and wife, as an adult — which helped me create necessary perspective on those experiences to write about them. I don’t think I could have finished the collection without moving home, or without feeling out of sorts in places like Michigan.

CD: Back Talk is your first published story collection, and it’s getting a lot of advance praise from many prominent writers for its portrayal of realistic women. How did you go about writing stories incorporating women whom readers can love and relate to? Obviously, it’s important that women are portrayed this way, but why do you think it’s so pressing to have a book like this one come out right now?

DL: My work has always been realistic; it’s my default mode. But realism is often messier than what many narratives offer us, particularly when it comes to how women should behave or want, and that is what I wanted to create on the page; women and men who were complex and believable. Plus, I don’t think realistic or true necessarily means lovable — we often love imperfect people.

As for relatable, I do hope some readers see a part of themselves in a character, but even more, I hope they have their own experiences expanded — or simply begin to believe that another experience exists. We have so far to go as a culture in making space for stories that are different from what we’ve seen. This is a small thing literature can do. I hope that the stories in Back Talk might give someone the fuel to write their own experience or the experience of women they know. The work of so many women writers has done that — and is still doing that — for me now.

CD: In multiple stories of this collection, unexpected relationships arise between people — the seller of an apartment and the potential buyer, a widower and his babysitter. How did you come up with these unique relationships?

DL: In any city, but particularly for one as crowded and fearless as New York, you often bear witness to very private moments whether that is through apartment walls or passing someone in the street. Knowing when to respect that space and when to step into it is something I’m hyper-aware of as a native New Yorker. There’s a lot of story in how a character reacts or changes from those boundaries being loosened and crossed, in particular the empathy that is possible in those moments, between not-exactly strangers. Also, for this collection I thought a lot about the conflation of the feminine with intimacy and care taking — women often don’t ask for the intimacy they are in, and are assumed to be comfortable in it, when of course many of us are not — and so it seems natural that many of the characters in my stories find themselves in deeper than expected.

CD: Each of the stories in this collection revolves around common and/or un-extraordinary events, some of which are portrayed in a slightly different-than-normal light, and as mentioned in the last question, many are based around perhaps accidental, perhaps fleeting relationships. For example, Back Talk is about a hookup at a party between a girl, the narrator, and a boy she barely knows. What made you decide to title your book after the story Back Talk?

DL: The story itself contains a lot of themes that are important to my work: a young woman at a pivotal moment in a conversation with herself, disappointments, a moment of choosing silence or talking back, the consequences of wanting if you’re a woman, questions of power. I wanted, too, to turn that idea of what that phrase means — mouthy, rude, out of line — on its head some.

CD: You’ve said that some of the stories in this collection were written as long as ten years ago. How did it feel compiling a full book of stories? How did you decide which to include? In your opinion, how do the stories from when you were in grad school differ from the ones written more recently?

DL: It feels amazing to gather work that’s been ongoing for a long while, since roughly 2002. At some point I cut a couple of stories that centered on male characters, not simply for this fact, but because I couldn’t make them as strong as the others, and wanted to make room for more women in the collection. The more recent stories were, for the most part, quicker to write because I had simply gotten better at writing, and often knew sooner what I was aiming for in a story, what I wanted to say or how I would say it. I think they’re more direct, less afraid than my earlier stories (though some have been revised to be bolder than I could have been when I drafted them). They also benefit from the life experience I’ve amassed in that time, personal shifts and aging for myself and those around me, that opened me to new experiences less available to me in my mid-twenties, when I was in graduate school.

CD: How do you balance being a mother to two daughters with writing? How does being a mother affect your writing?

DL: Motherhood or writing is the day job, depending on the day. It gets balanced the way anyone with any other gig does it: flexibility, and in my case, lots of timers and reminders to segment my time. Parenthood ignited the sense of time passing (a.k.a. the inevitable march toward death); it reinforced the understanding that no one was waiting for my work. It made me more aggressive with both my subject matter and putting myself out into the world. I’d also say that early days at home with babies made my mind restless in a necessary way, and taught me how to use what time I had in a way that wasn’t possible for me in my pre-child life.

I’ve always written about women and girls and family life — most of the stories about young girlhood were in fact written before I had kids — but experiencing something I’d only imagined definitely heightened my work on the page. I gained a sense of my childhood from the other side, and an introduction to new universes of people and what they cared about and feared and the particular complications of family life. I began to think more carefully about the through lines of those stories. Here I was at playgroups and playgrounds and classrooms, with their attendant rules and expectations and cultures. In these spaces, all these women (and they were mostly women) were carrying the girls they were, how they had been mothered and wanted to mother themselves, what they’d given up and still wanted.

CD: What advice do you have for young writers?

DL: Make friends with other writers, seeking not just your best readers, but people with whom you can be forthcoming about your challenges and triumphs. I could not survive the particular weirdnesses of the writing life without my circle of support cheering me on and commiserating and doling out tough love when necessary, nor without doing this myself for them; it helps to be engaged in conversation with folks who help you see the big picture.

Believe in process over product. Don’t obsess over the number of words you put down or publications. Committing the time to the work is the most you can do, the little thing you can control. There’s no guarantee that you’ll produce what you expect in that time, but getting comfortable with being in that chair in a disciplined way is the best you can do, and it’s enough — whatever amount of time that is. Over time, that collective work will end up in your product, even if you delete a lot of the words.

CD: What’s next for you?

DL: I’m currently working on a novel about motherhood and women’s movements and memory.