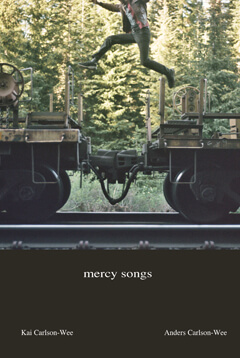

Interview: Anders and Kai Carlson-Wee

November 30th, 2017

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with co-authors Anders Carlson-Wee and Kai Carlson-Wee about their collection Mercy Songs, hitchhiking across the Midwest, exploring new mediums of poetry, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with co-authors Anders Carlson-Wee and Kai Carlson-Wee about their collection Mercy Songs, hitchhiking across the Midwest, exploring new mediums of poetry, and more.

**

Meghan Chou: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Anders Carlson-Wee: We grew up in Minnesota. Our parents are both Lutheran pastors and served congregations in Northfield, Fargo-Moorhead, and Minneapolis. Our great-grandparents were part of a wave of immigrants from Norway who settled in Minnesota around 1900. When I bicycled across the country twice in the 2000s, I had the most illuminating, heartfelt, and layered conversations with strangers in the Midwestern states (although the craziest stories from those travels came out of the South). I moved back to Minneapolis two years ago, after being away for thirteen years. I would say much of who I am is Midwestern, and that influences how I think, act, and write.

Kai Carlson-Wee: Anders and I grew up in a small town in southern Minnesota, called Northfield. We lived a block from a cereal factory and a train yard and spent the bulk of our time roaming around town on our bikes. It was a very American childhood. We raced go-carts down the street and stuff like that. When we got older our family moved up to Fargo, North Dakota, where we went to high school. Fargo was more blue collar, more prairie, but still very Midwestern. You wouldn’t exactly call it a destination city, it was more of a place people got lost in or stranded in and somehow failed to leave. When I graduated from high school I moved out to California to be a professional rollerblader. I felt more comfortable on the coast, more myself, but I kept bouncing back and forth. I went to college in Minnesota, moved to Portland, moved back. I think my spirit belongs to the stuff out west, but my heart is stubbornly Midwestern.

MC: The theme of brotherhood is strong in many of the poems in Mercy Songs. How do you, as brothers, inspire each other and how did growing up in the Midwest influence your relationship with one another?

ACW: While Kai and I were growing up in northern Minnesota we were serious rollerbladers, and skated semi-professionally for a while. Together we designed and built a skate park in our garage, using materials we stole from the half-finished homes on our block. The garage skate park gave us a place to skate every day during Fargo-Moorhead’s subzero winter, although it wasn’t much warmer in there. When you share an interest with a brother, you’ve got a partner in crime—someone to commiserate with, someone to plan with. And you have someone keeping you in check. On school nights, we’d skate for up to five hours, often going back out into the cold after dinner for more. I don’t think either of us would have stayed as focused without the other one. As for being from the Midwest, our landlocked small-town life didn’t offer many options—for entertainment, for friends, for ideas—and I think that helped Kai and I form an extra strong bond. It also shaped our imaginations. I think of the Midwest as having a deeply physical imagination; this takes form in everything from the protestant work ethic, to the suspicion of things that are too far “out there,” to a trust in, and love for, the things of the earth: the things you can see and touch and smell and hear and feel. This isn’t all positive. Or healthy. But I think it’s had a profound impact on how Kai and I think, on how we relate to each other, and on how we write.

KCW: Well, we grew up skating together, and when you’re a skater, especially a rollerblader, you get a lot of adults trying to tell you to quit. Cops, security guards, teachers, parents, even your friends. You start to develop an anti-authority thing and you become pretty insular and self-reliant. When we first moved to Fargo, Anders and I didn’t have any friends so we turned to each other for support. We spent hours and hours skating in our garage learning tricks on the ramps and rails we built. When we went street skating we had all these confrontations with authority figures and random people who wanted to mess with us and we developed a bond around that. We had to watch out for each other. I don’t know if the Midwest made it any different, but there’s a way in which the Midwest is easily dismissed by the larger, more cosmopolitan zones in this country. I think Anders and I both have a chip on our shoulder about systems or individuals who assume hierarchical positions of power. We tend to empathize with underdogs and outcasts, and the place we grew up in probably informed that.

MC: In Mercy Songs, a collection the two of you co-wrote, the poems alternate voices and play off of one another like a call and response. What are the benefits and difficulties of co-writing a collection of poems?

ACW: As brothers, we’ve been having an ongoing conversation our whole lives; Mercy Songs is a natural extension of that conversation, but the book makes it accessible to an audience, which allows the world to interpret and sculpt our voices for its own needs. That’s scary, but also liberating. I think it lets us move forward, and let go, in a sense. It’s also been very cool to be able to read together from the book, enacting the call-and-response format for a live audience.

KCW: The poems in Mercy Songs were written independently of each other, but they were written about similar experiences, so the connections between them are mostly accidental. It’s not like we sat down and said, let’s write a chapbook about traveling together, it was more like we noticed there were similar themes in our work, characters, ideas, landscapes, etc., and the poems already had resonance. The project of putting the book together was more like shuffling cards, so the construction was actually pretty easy. I think the danger of doing a project like this is that the poems might feel out-of-sync, either too similar, or too different, and our goal was to arrange things in a way that felt harmonic and had some sort of narrative flow. Not sure if we pulled it off, but that was the idea.

MC: Many of the poems in Mercy Songs revolve around your adventures train-hopping cross-country together. There are references to “bulls” (the train security guards) and descriptions of the intense heat. How did these trips change your perception of the Midwest and the landscapes you write about?

ACW: Train-hopping is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. It leaves you utterly submitted to the world—the elements, the weather, the unceasing pulse forward—and reduces you to your basic desires and needs: water, food, shade, sleep, companionship. It cracks your skin, bloodshots your eyes, parches your throat, rattles your spine, and steals your mind away to the edge of reason and sanity and self. It’s an overwhelming tactile experience. And it’s not uncommon to experience hallucinations, waking dreams, spatial disorientation. Every time I’ve hopped trains I’ve heard voices. I don’t mean I thought God was talking to me; I mean you’re so worried about getting caught, so shaken by the train’s heaves and clinks and hisses, so strained by the long nights in the alternating dark and sharp light of railroad yards, so worn out from the waiting and hiding and the nothing happening but jolts and flashes and speed, that you start needing the stimulus around you to mean something—you start needing the world to pertain to you. I think this is the intrinsic primitive impulse that births religion, storytelling, and art. We need the world to pertain to us, and for us to pertain to it. We crave this. A sense of order. Of cause and effect and consequence. For me, train-hopping has been a way to experience that need, sharply. But all art and religion deals with this need. Poetry offers acute access to it. As for a specific location, such as the Midwest, train-hopping gives you the experience of passing through a place—a rush of time and perspective, which alters what remains the same, as your position changes. And like I was describing, it also takes you into a condition where you can peel back the veil, slightly and momentarily, like a good poem can do.

KCW: I don’t think it changed anything, exactly, but putting the book together made me think about the particular culture we’re trying to illuminate. Ever since I was young, I’ve been interested in the gothic side of the Midwest, the dark and weird shit. People have explored this element in the south, but they haven’t really nailed it down in the Midwest. When you think about literary representation, you have the family dramas of Willa Cather, stuff like Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom, the quirkiness of Garrison Keilor, the lonely isolationism in Stoner and Winesburg Ohio, the natural beauty and subtlety of Robert Bly, but none of these versions line up with the weird idiosyncratic violence and surrealism I experienced when I was younger. Films like Fargo by the Coen Brothers and Badlands by Terrence Malick are more invested in this quality. Music albums like Separation Sunday by The Hold Steady and Rooster by Charlie Parr are also in this direction. Traveling around the country helped me see different versions of American weirdness, but there’s a particular quality in the Midwest that I’m interested in writing about. It has to do with spiritual poverty and the way people use pleasantry and morality to justify violence and to combat an existential dread of the land.

MC: Your joint short film, Riding the Highline—which won a Special Jury Prize at the Napa Valley Film Festival, among other awards—incorporates visuals with recitations of poetry as you ride from Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Wenatchee, Washington. What did you learn from documenting this trip about the connection between poetry and film as well as the power of combining the two?

ACW: Riding the Highline allowed us to frame two lyric poems with the larger narrative context of the film’s story, which seems to have resonated with a wide audience. And it continues to allow us to sneak poetry into a huge range of venues: high school auditoriums, dive bars, art exhibitions, college classrooms, film festivals, hobo gatherings, art crawls, and lots of people’s living rooms (via the internet). We’ve had people come up to us and quote lines from our poems, often saying something like “I’ve never read much poetry, but now I will.”

KCW: Poetry and film both operate on a linear timeline. They’re both potent, powerful mediums, and can convey a lot of feeling in a small amount of space. Film is more superficial, but it creates more of a total atmosphere. Poetry is generally deeper, more internal, but also more subtle in the way it hits your emotions. If the two are combined in a natural, harmonic way, the results can be powerful. When we’ve screened Riding the Highline at film festivals, people always ask why we wanted to combine the two mediums, what genre we’re trying to invent. But I don’t know, to me it just seems like an obvious thing to do. I get a little tired of reading poems in books. Black and white, print on page. I love books, but I don’t see why writers aren’t expanding their ideas of what poetry can become. When you look at what’s happening with something like Instagram poetry, you can see there’s a real interest there, an appetite. Rather than laughing at how awful it is, I think we should take some notes and start seeing these forms as a sign of health, of new directions in poetry.

MC: What is the most memorable trip the two of you have taken together and how did it affect your life philosophies?

ACW: One time Kai and I hitchhiked from Minneapolis to Chicago by way of Wisconsin, and we had the most insane rides. Every person that picked us up was more unhinged than the one before. We got a ride from a young man who’d had a heart attack from doing too much coke on his eighteenth birthday. We got a ride from a single mom and her five-year-old son, who sat beside us eating a Happy Meal; she kept saying if we were any bigger she wouldn’t have picked us up. We got a ride from a man with fresh wounds on his face, the result of fighting his friend when his friend caught him stealing his four Labrador puppies; he said he stole the puppies because his friend was letting them die of heatstroke in a backyard cage, and he picked us up because he needed someone to give the puppies water; they sat on our laps and drank from a sour cream container (a much, much, much longer story). That trip affected my life philosophy about Wisconsin.

KCW: My favorite trip with Anders was a hitchhiking trip we took back in 2006. I had just graduated from college, Anders had recently finished high school, and our plan was to hitchhike from Minneapolis to Chicago with no real agenda. I think I had just broken up with a girlfriend and was feeling slightly nihilistic about everything and we just wanted to get on the road and take things as they came. Somehow, every ride we caught was extremely weird, and we ended up riding with this guy named Rick who was wildly spun out on meth. He had six little St. Bernard puppies in the car and he was talking a mile-a-minute and ranting conspiracy theories about George W. Bush. We honestly thought he was going to kill us, but then he didn’t, and everything turned out okay. We ended up at a Phil Lesh concert and then accidentally attended the gay Olympic games in Chicago, where everyone thought we were a couple. The whole trip took place in a week but it seemed like an endless surreal dream. Still one of the most memorable trips we’ve taken.

MC: After returning from these trips of solitude and excitement, how do each of you find places and time to write in your daily lives?

ACW: I live in Minneapolis and write poetry full-time. I dumpster dive for most of my food and live a humble life. I piece together an income from touring, publishing, teaching, awards, grants, etc., but I wouldn’t be able to sustain this lifestyle for very long without the generous fellowships I’ve received from the NEA, Vanderbilt University, and the McKnight Foundation. Those three fellowships have paid for the lion’s share of my life for the last five years, and I am forever grateful.

KCW: Almost everything I write is autobiographical and based on experience, so I need these periods of adventure and wandering around. I need weeks of doing things randomly, without agendas. If I’m being too responsible with my life, my poetry gets fake. It’s not that it gets bad exactly, it just gets repetitive and boring and starts to parody itself. I never want to get to the point where I’m writing poetry for the sake of writing poetry, either because I’ve committed myself to a poetry “career” or because I’ve established too much of my identity around previous work. I want my poems to keep springing from inspiration and impulse, rather than expectation. Right now, I’m lucky enough to be on an academic schedule, so I can travel and write during the summers. During the school year I have three days a week to do whatever I want, and I usually spend that time at coffee shops, working on poems, reading, taking photos around the city. This makes me a difficult person to date or be friends with, but I don’t really mind. I think at the end of my life I’ll regret not having more friends, but I’ll regret less the poems I’ve written, the time I spent alone.

MC: What’s next for each of you?

ACW: I’m finishing my first full-length poetry collection and spending the summer in Guadalajara. Starting in the fall, I’ll be touring heavily. If you want me to tour through your town/school, email me: anderscarlsonwee@gmail.com

KCW: My first full-length collection of poems, RAIL, is coming out with BOA Editions in Spring 2018. I’ve been working on the cover and have started production on a series of short films, which I’m hoping to release with the book. The idea is basically to make a visual version of the poems, with video, audio, photographs, etc. I want it to be a stand-alone piece, rather than a series of music videos. Hopefully it doesn’t suck.

**

Anders Carlson-Wee is a 2015 NEA Creative Writing Fellow and the author of Dynamite, winner of the 2015 Frost Place Chapbook Prize. His work has appeared in Ploughshares, New England Review, AGNI, Poetry Daily, The Iowa Review, Best New Poets, The Best American Nonrequired Reading, and Narrative Magazine, which featured him on its “30 BELOW 30” list of young writers to watch. Winner of Ninth Letter’s Poetry Award, Blue Mesa Review’s Poetry Prize, and New Delta Review’s Editors’ Choice Prize, he was runner-up for the 2016 Discovery/Boston Review Poetry Prize. His work has been translated into Chinese. He lives in Minneapolis, where he serves as a McKnight Foundation Creative Writing Fellow.

Kai Carlson-Wee is the author of RAIL (BOA Editions, 2018). He has received fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and his work appears in Ploughshares, Best New Poets, New England Review, Gulf Coast, and The Missouri Review, which awarded him the 2013 Editor’s Prize. His photography has been featured in Narrative Magazine and his poetry film, Riding the Highline, received jury awards at the 2015 Napa Valley Film Festival and the 2016 Arizona International Film Festival. A former Wallace Stegner Fellow, he lives in San Francisco and is a lecturer at Stanford University.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ben Ratner spoke with photographer Tara Reeves about her creative process, showing people things they’ve never seen, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ben Ratner spoke with photographer Tara Reeves about her creative process, showing people things they’ve never seen, and more.

Alyssa Zaczek’s story “Salt in the Pan” appears in

Alyssa Zaczek’s story “Salt in the Pan” appears in

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Stephen Kiernan about his book The Baker’s Secret, researching World War II, finding lightness in tragedy, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Stephen Kiernan about his book The Baker’s Secret, researching World War II, finding lightness in tragedy, and more.

Kali VanBaale’s story “The Girl in the Pipe” appears in

Kali VanBaale’s story “The Girl in the Pipe” appears in

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Michael Bazzett about his work The Interrogation, the fluid nature of identity, learning to incorporate humor, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Michael Bazzett about his work The Interrogation, the fluid nature of identity, learning to incorporate humor, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Edward McPherson about his book The History of the Future: American Essays, shaping an essay collection, the multiple perspectives of history, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Edward McPherson about his book The History of the Future: American Essays, shaping an essay collection, the multiple perspectives of history, and more.