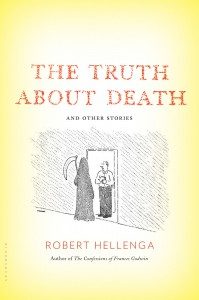

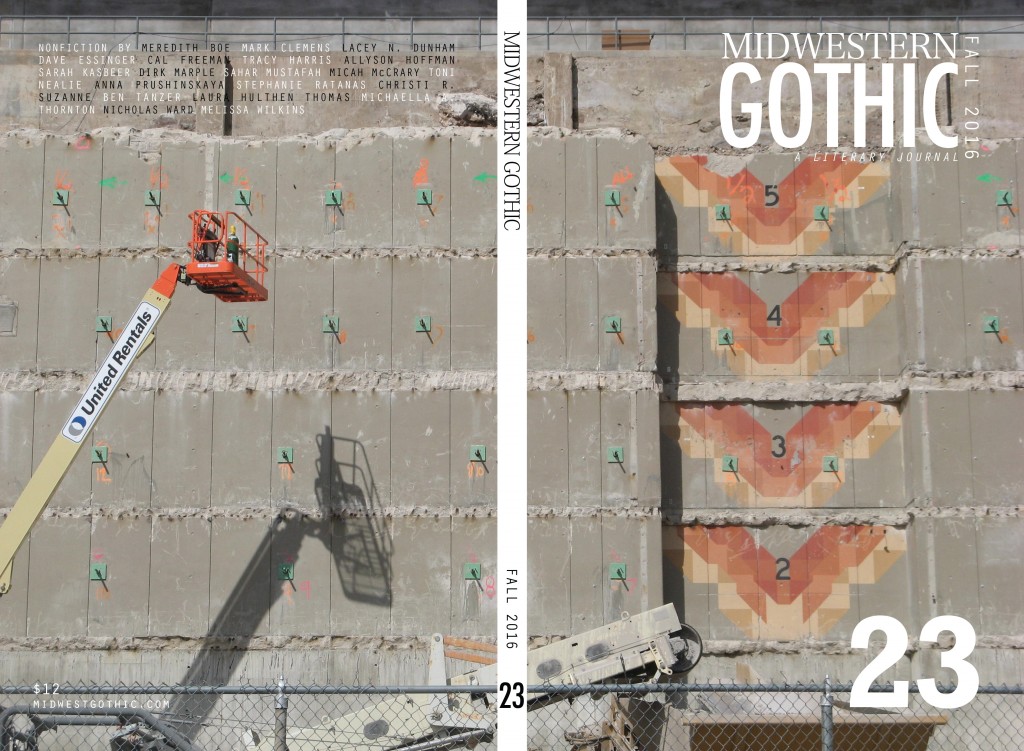

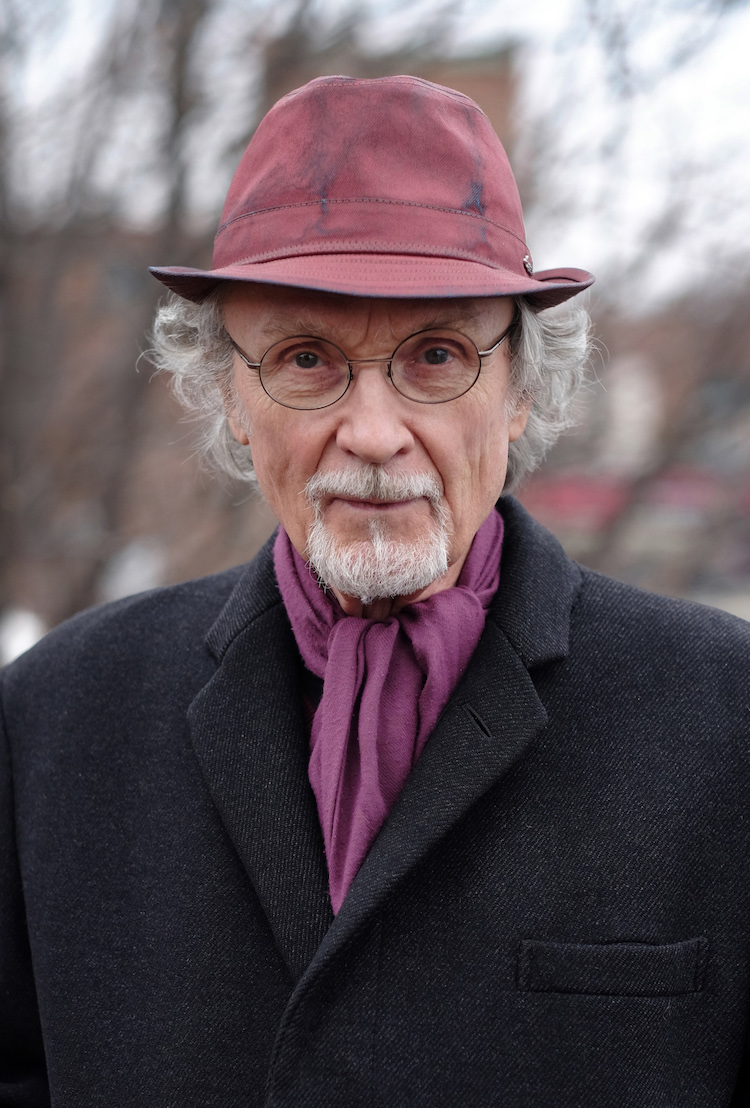

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Robert Hellenga about his collection The Truth About Death and Other Stories, the connection between death and love, neutralizing the ‘eye-roll response’ in emotional scenes, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Robert Hellenga about his collection The Truth About Death and Other Stories, the connection between death and love, neutralizing the ‘eye-roll response’ in emotional scenes, and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Robert Hellenga: I was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where my father was a commission merchant selling produce that came by boat from the Benton Harbor, MI, produce market, the largest farmer’s market in the US at the time. We spent our summers in Milwaukee, and the rest of the year in Three Oaks, Michigan — a town of 1800 people which, when I was growing up, had two drug stores, a large department store, several grocery stories, a good public library, a museum, a railroad station, a movie theater, and no Wal-Mart.

I attended the University of Michigan, got married, spent a year at The Queen’s University of Belfast, in Northern Ireland, then another year at the University of North Carolina, then Princeton, where I got my PhD. None of these places resonates for me as much as my two childhood home towns — Three Oaks and Milwaukee — and my present home town, Galesburg, Illinois. (And Florence, Italy, where my wife and our three daughters and I spent thirteen months in 1982-1983.)

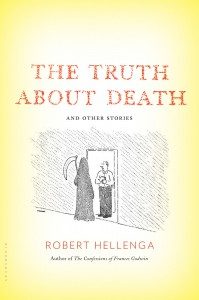

GE: Your new collection of stories, The Truth About Death and Other Stories, takes place in Galesburg, Illinois and Rome, Italy, both places you have lived at some point in your life. How does where you’ve lived influence how you write about place, as well as other aspects of your writing?

RH: I see, in retrospect, that the Italians who worked for my father on the market in Milwaukee gave me a glimpse (and a taste) of a world very different from small town life in the Midwest (Three Oaks), a life that was more colorful, more pleasure-oriented. Sexual intercourse was regarded as the highest good. They also gave me a taste of la dolce far niente – the sweetness of doing nothing – something very different from the ceaseless striving to get ahead I’ve come to experience as normal.

This polarity has shaped my writing, but it wasn’t till our family spent a year in Florence that I began to think of myself as a Midwesterner. Margot, in The Sixteen Pleasures, and Woody, in The Fall of a Sparrow, are my first self-conscious Midwesterners. And both of them are able to hold their own and flourish in Italy, in a culture older and more cynical and (presumably) more sophisticated than their own.

Push comes to shove in a later novel, The Italian Lover, that brings these two characters together. Margot and Woody, now in their fifties, are in love. Margot wants Woody to stay in Italy, but Woody wants to go ‘home,’ to a small town in Illinois, and he wants Margot to go back to Illinois with him. She could, he suggests, work as a book conservator at the University of Iowa (an hour-and-a-half away). Margot chooses to stay in Florence, but she never gets over “the fear that her true home was elsewhere, that her real life – her true spiritual life – was not here in Italy, here at her work bench in her very own studio on Lungarno Guicciardini, or in her very own apartment in Piazza Santa Croce, but waiting for her back home, back in Chicago, back in the big house on Chambers St., waiting for her to take up where she’d left off.”

And speaking of houses: The houses we’ve lived in have become icons in my imagination — three in the Midwest and one in Italy: the big Victorian house we lived in in Galesburg, which we sold to our daughter and her husband (The Sixteen Pleasures, Philosophy Made Simple); the fantastic apartment in Borgo Pinti where we lived as a family for a year (The Sixteen Pleasures); the house in the woods near Monmouth that we owned for eleven years (Snakewoman of Little Egypt); and our present apartment (The Confessions of Frances Godwin) in Galesburg.

GE: The Truth About Death is true to its title, and follows two funeral directors meeting in Rome to prepare the body of a close relative. Did writing from the perspective of people who deal with death often change how you yourself view death? What was most difficult about dealing with this subject?

RH: Hildi, one of the POV characters in The Truth About Death, wants to go into the funeral business with her father because she thinks of the family funeral home as a place where the big questions get asked, if not answered. I like to write about death for the same reason, to address the big questions: On the one hand, death is perfectly natural; on the other hand, as Simon, Hildi’s father, reminds his daughter after they finish prepping the body of Simon’s father: Remember what Father Cochrane says at the beginning of every funeral: “Behold, I show unto you a mystery.” And then he puts his hand on his father’s forehead and says it again: “Behold, I show unto you a mystery.”

Did my own views change? I’ve come to believe, as Hildi does, that there was real value in the way that families used to prepare their dead. Hands-on experience. What would this value be? Hildi doesn’t think it’s something you can “tell.” Her father is skeptical, but in the end, when Hildi is killed in Rome, he holds her hand as the Italian undertaker washes her body. I have not done anything like this myself, but times are changing, and funeral customs are changing. Home funerals in which family members help prepare their dead are becoming easier to arrange.

The most difficult thing? Writing about the death of Olive, the dog. Olive’s death was based on the death of our own dog, Maya, who was diagnosed with liver cancer on a Monday and dead on Thursday. I’d like to read the Oliva passages aloud at a reading, but I can’t even read it to myself without tearing up. I think the special difficulty is that you can’t explain death to a dog. Of course you can’t really explain death to anyone, but with a person you can at least talk things over.

GE: The Truth About Death deals with love alongside of death. How do you see the two aspects of life as needing to be related?

RH: Death, or the prospect of death, is a lens that clarifies our relationships. It puts a lot of pressure on us to do what needs to be done, now. If you love someone, let them know now, before it’s too late. This is the sort of advice, as Margot points out in The Sixteen Pleasures, that you read in Ann Landers. It’s still good advice, however. The irony in The Sixteen Pleasures is that Margot’s mother was trying to tell her family, though we never find out exactly what she wanted to tell them because the tapes she made were blank. The tape recorder had malfunctioned.

It’s hard to do better than the following inscription, which appears (in Latin) in the death notice of Alexander Lenard, the man who translated Willie the Pooh into Latin: “Against the strength of love, you will find no herb. Against the strength of death, no herb grows in the garden.” This is what Woody finally puts on the tombstone of his daughter, who was killed in a terrorist bombing in Italy in 1982.

GE: Your writing seems to very naturally mimic life, drawing the reader into the stories and making them feel deeply, especially with the theme of death. What is your process like when crafting emotional scenes?

RH: On the one hand, I try not to hold anything back. On the other hand, I try to guard against the eye-rolling response. For example: in The Fall of a Sparrow Woody says to the terrorist (a young woman) who placed a bomb in the station in Bologna, the bomb that killed his daughter: “I have to love you because hating you is too hard.” I knew this line could be trouble. I tried to neutralize the eye-rolling response by including a lot of hard things in the scene, by having Woody almost strangle the woman, for example; by having the terrorist woman resemble Woody’s daughter; by trying to show that I was aware of all the complexities of this encounter. I took the line out several times and then put it back in. Several reviewers singled out this scene as one of the best in the book. But the New York Times reviewer, who in fact liked the book, looked up at this point and rolled his eyes: as the novel “winds down doctrine and philosophy prevail, and Woody, supposedly on the brink of self-knowledge, finds himself making pronouncements like, ‘I have to love you, because hating you is too hard.’” Oh well.

Ditto for all big emotional scenes, especially sex scenes. As a writer you put your erotic imagination out on the line for everyone to see. You don’t want your readers to roll their eyes. You need something that goes beyond a blow-by-blow description. Blow-by-blow descriptions are a dime a dozen. You have to give your readers a reason to want to imagine the scene that you’re inviting them to imagine, something beyond prurient interest. Someone has to be learning something, discovering something. And that means that you, as a writer, have to be learning and discovering something too. There’s no formula.

I didn’t hold back in the following passage from Snakewoman, for example, but I tried to provide a context that would ward off the eye-rolling response: After a mutually satisfying experience in bed Jackson, an anthropologist, asks Sunny, a biology student, “What just happened?” She gives him a biological account of her orgasm—pelvic area engorged with blood, muscle contractions, etc. “Why?” she asks. “What do you think happened?”

“You took me inside you,’ he said, ‘and devoured my seed when I was most vulnerable, and you were most triumphant. I explored your dark continent at my own risk. You lured me on. But because I survived the encounter, you will now share your great riches and power with me, because you love me.”

“It wasn’t really funny, but I started to laugh. ‘Is that what really happened?”

“‘That’s what really happened,” he said.

“I thought maybe he was right.”

Sun Times reviewer: “Talk about purple prose. But also talk about how skillfully Hellenga injects humor to reduce the swelling.”

GE: While it may be tempting – and even expected – to write about death with a sense of irony, The Truth About Death deals with it head on, avoiding the classic jokes and fully confronting the reality, emotional impact, and inevitability of death. Why did you choose to write about death this way, and was it difficult to resist the usual cop outs?

RH: Maybe because I’m a Midwesterner. Just kidding. Actually, I’m not just kidding. I’m thinking of a time I was doing research in Bologna. I joined the British Institute so I could use their library. The British Institute doesn’t stock any American novels, only British, so that’s what I read. Everything was ironic. Absolutely everything was undercut by irony: every generous impulse, every act of kindness, every moment of tenderness… After a while I couldn’t take it any more. I complained to the Italian friends I was living with, and Franco said: “That’s because England doesn’t count for much anymore.”

Irony isn’t always a cop-out of course. At its best it’s a way of showing that you’re aware of other ways of looking at whatever you’re looking at.

GE: In this collection of stories you revisit characters from a previous story, “Pockets of Silence” that appeared in The Chicago Tribune in 1989 as well as your debut novel Sixteen Pleasures in 1994. What made you decide to revisit this story in this most recent collection? What was it like continuing a story that started almost 30 years ago? Has time changed how you view the story?

RH: I’ve had more responses (letters and now emails) to this story than to anything else I’ve written. Maybe it’s because the ending took me completely by surprise. I couldn’t figure out what was going to be on the tape that Margot’s mother makes for her family as she’s dying. So I just stopped, left the tape blank.

And maybe the story stays with me because I’m like Margot: I still have unfinished business with my mother, who was a student at Knox College, where I taught English for almost forty years. Too late now.

GE: What’s next for you?

RH: I’m working on a novel about a rare book dealer. I’ve been thinking that I’m in over my head, though today I’m feeling better because I’ve figured out a way to tell part of the story from a woman’s POV. I feel more energized writing from a woman’s POV for a couple of reasons. One, we have three daughters and I’m used to looking at the world through their eyes. And two, women’s stories still have a kind of built-in urgency to them, a sense of breaking new ground, that appeals to me.

I don’t want to say much about it because everything is still in flux. I will say, however, that this summer I’ll be attending the Colorado Antiquarian Book Seminar in Colorado Springs — a week of intensive classes on the rare book business. We’ll see what happens.

**

Robert Hellenga grew up in Three Oaks, Michigan, a typical Midwestern small town, but spent summers in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where his father, a commission merchant with a seasonal business, handled produce that was shipped there from what was then the world’s largest farmers market, in Benton Harbor, Michigan. The men who worked for his father were almost all Italians, and in retrospect he sees that this is how he got his first sense of Italy as something opposed to small-town Midwestern Protestant culture — a theme that has shaped a lot of his writing.

He met his wife (Virginia) at the University of Michigan, spent the first year of their marriage in Belfast, Northern Ireland, spent a year in North Carolina, and started having children when he was in graduate school at Princeton.

Robert taught English literature at Knox College, in Galesburg, IL, from 1968 to about 2000. During his tenure at Knox he directed two programs for the Associated Colleges of the Midwest, one at the Newberry Library in Chicago and one in Florence, Italy, and spent a year at the University of Chicago on a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. He has spent quite a bit of time in Florence and Bologna, and in 2009 he and his wife spent six weeks in Verona, where Robert was a visiting writer at the University of Verona, and in 2012 they went to Rome for eight weeks.

Robert started writing fiction at Knox, which has a strong creative writing program, published his first story in 1973 and his first novel (after 39 rejections) in 1994. His most recent book is a collection of stories — The Truth About Death and Other Stories — and he is currently working on a novel about a rare book dealer who sets up shop in a small town on Lake Michigan.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Robert Hellenga about his collection The Truth About Death and Other Stories, the connection between death and love, neutralizing the ‘eye-roll response’ in emotional scenes, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Robert Hellenga about his collection The Truth About Death and Other Stories, the connection between death and love, neutralizing the ‘eye-roll response’ in emotional scenes, and more.

Andrew Bode-Lang’s story “Body and Soul” appears in

Andrew Bode-Lang’s story “Body and Soul” appears in  Laura Misco’s story “Exorcising Mike” appears in

Laura Misco’s story “Exorcising Mike” appears in

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Lawrence Coates about his book The Goodbye House, how his time at sea prepared him to become an author, unsettling characters through specific settings, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Lawrence Coates about his book The Goodbye House, how his time at sea prepared him to become an author, unsettling characters through specific settings, and more.

Chelsea Voulgares’ story “Midnight Walk, 1993” appears in

Chelsea Voulgares’ story “Midnight Walk, 1993” appears in  James Figy’s story “Scavenger Hunt” appears in

James Figy’s story “Scavenger Hunt” appears in