Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with poet Anne Champion about her collection The Good Girl is Always a Ghost, showcasing historically unknown women, politics in poetry, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with poet Anne Champion about her collection The Good Girl is Always a Ghost, showcasing historically unknown women, politics in poetry, and more.

**

Jo Chang: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Anne Champion: I was born and raised in Kalamazoo, Michigan. I lived there until I was 25.

JC: You currently live and teach in Boston, Massachusetts. How does this environment differ from the Midwest, if at all?

AC: I’d say one of the largest differences is political: Boston is simply a more liberal area. While Kalamazoo was fairly liberal due to it being a college city, I was met with conservative viewpoints regularly, which I rarely encounter here. There are vibrant activist movements here, and there is a broad diversity of people from all over the world. Even though Boston is relatively small, it has the big city feel that I never found in Michigan. With that comes a much higher cost of living—and that’s a huge burden. It’s becoming more gentrified and it is definitely pushing lower income people out of it year after year, becoming a city for the 1%. So, there are certainly pros and cons.

I miss some things about Michigan. In Boston, you often feel like most people are just passing through—for school or for travel or for temporary work until they move to a cheaper area—while in Michigan you felt like the community was fairly solid. And I deeply miss the Great Lakes, particularly Lake Michigan, where I spent a lot of my youth.

JC: Your forthcoming poetry collection, The Good Girl is Always a Ghost, is a collection of persona poems that gives readers a glimpse of the lives and struggles of various women figures from history. Unsurprisingly, given the historical weight of the book, you have stated that writing The Good Girl is Always a Ghost involved a lot of heavy research. Could you describe a bit about that process? How did you figure out where to begin, and how to showcase women who are not historically well-known?

The book began with women that are well-known that were pivotal in my child development. I was a feminist before I ever knew what a feminist was. I deeply admired my father, who was a pilot and served in the Air Force, and therefore I wanted to do what he did. I was always looking for women that did things like my father. My dad, who never identified as a feminist in my youth, unknowingly fueled my belief in women’s equality by introducing me to women like Annie Oakley and Amelia Earhart. I had a short curly wig and a leather pilot’s hat that I would wear to be Earhart and a toy rifle and cowboy hat to be Oakley. These women ignited my imagination. As I got older, beauty standards sunk their talons into me, and I was drawn to women like Marilyn Monroe and Judy Garland—tragically beautiful to the extent that everything else about them was blotted out. In my 20s, I was a poet, and, like many young women before me, went dizzy under the spell of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton.

So, the poems began with them, but once I realized I’d be crafting a book to iconic women in history, I wanted the collection to be inclusive and diverse, and I wanted it to speak to women who history had not been as kind to, at least in America. I wanted women of a variety of ethnicities, religious backgrounds, ages (including children), and sexualities. I also wanted transgender women (and I included one transgender man) along with women with disabilities. That inclusiveness, as well as the diversity of accomplishments, was the most important thing.

Once I knew what I needed in the book, then I knew what to look for. It was often a process of directing my research to a specific country. For example, I directed my search to Afghanistan and found the feminist activist Meena Kamal, who was assassinated for her beliefs in the 1980s. I directed it to Japan and found Sadako Sasaki, a child who lived through Hiroshima, only to die of cancer due to radiation exposure years later.

I researched in a variety of ways. When I could, I wanted to watch documentaries or interviews of them, in order to get a sense of their voice or personality. But for many, this wasn’t possible, so it may have consisted of reading a book or some articles about the person and searching for the facts that pulsed until the inspiration blossomed.

JC: The Good Girl is Always a Ghost uses multiple perspectives from various women figures in history. In order to write each poem in another voice, did you have to mentally prime yourself beforehand, in order to inhabit each new persona?

AC: Yes, sometimes, but not always. There are some poems where I’m trying to be more faithful to the voice of the historical figure than others. One example would be Christine Jorgensen, who was the first transgender woman to become widely known for having sex reassignment surgery in the U.S. She had such a unique, brazen voice that it was important for that to come through in the poem. Another was Plath—as a poet, you really can’t write a poem to Plath unless it’s going to be good, because her voice is already such a haunting, unraveling thread of the fabric of American poetry. In the times I needed to prime, I just spent excessive amounts of time with those voices, so that I could absorb what I needed before writing.

But some poems are more tied to my poetic voice, as the act of the persona is a process of empathy to me. In using speakers and situations that were not mine, I imagined the emotional circumstances for myself as a woman—I found the parallels that bind me to these women, and I tried to acknowledge and honor the paths that they worked to open for women everywhere.

Still, other poems are odes and not personas. There are some women who I didn’t feel confident inhabiting their voices, or I felt that they were more deserving of an ode. I wrote odes to Rosa Parks, Wilma Rudolph, Amy Winehouse, Marilyn Monroe, Sandra Bland, and others. There are even some poems that began as personas until I realized that there was something problematic in my attempt to inhabit the voice, so I would revise it to an ode.

JC: Like your previous poetry collection, Reluctant Mistress, The Good Girl is Always a Ghost also addresses the multifaceted concept of womanhood, in all of its complicated forms. What draws you to this subject matter—why is it important? Who are some of the women who have greatly influenced your life, and why?

AC: I was raised in a pretty conservative household, and feminism was not regarded favorably. Therefore, my sense of identity was pretty limited to what was “gender appropriate.” It wasn’t until college that I was first exposed to feminism (by a male professor! Bless your heart, Keith Kroll). In that exposure, I was liberated. I realized where so much of my unhappiness and angst came from: low self worth, low confidence, the daily micro and macro aggressions of sexism, years of patriarchal abuse in romantic relationships, a lack of role models, a lack of political representation, the list goes on and on and many of these things still plague me.

And yet, I was free. Because now I knew that it was the culture that was ill, not me, and I knew that I was capable in everything I did. It gave me a well of strength: I don’t know what I would have become if I didn’t have it.

In being exposed to that, I was exposed to many feminist poets and writers. That influenced me, and the intimate issues regarding womanhood—which are so often dismissed as trivial, crazy, irrational, or melodramatic—were what I needed to give voice to in my writing at the time.

Most of my work is feminist to some extent, but my more recent work as branched out more in the political sphere, as I’ve engaged in peace activist work and I’ve devoted myself to writing about Palestine, capitalism, and U.S. policy in Latin America. Though, womanhood always comes up in those poems as well.

The historical women who most greatly influenced my life are in the book, and even the ones who I discovered while writing all became a part of me—I absorbed their stories and I carry their lessons with me. The women in my real life who have most influenced me are my sister and my close friends—I am surrounded by strong, talented, funny, creative, and inspiring women. Sisterhood is a powerful form of life support.

JC: Your poems address topics at the intersection of various political topics. Did you find your own political inclinations (perhaps unconsciously) influencing your poems?

AC: I find my political inclinations to influence my work very consciously. I don’t see any way around that.

But my poems are not advocating for any political party—quite the contrary actually, because I’m critical of both. I lean left, but I’m much farther left than the democratic party, whose policies in my lifetime have always been very center.

For example, I wrote a book of poetry about my time in Palestine witnessing the devastating military occupation and the effects of people living in an apartheid state. It’s impossible for me to see what I saw and write about that without it being seen as “political,” but both parties have allowed billions of taxpayer dollars to support the injustices I’m writing about.

In my view, my writing is centered on human rights and compassion, not politics, but in the political world, the denial of human rights and apathy are often what’s being advocated for. So, in that sense, my poems become political.

Even in writing feminist work, we feel as if we are only writing about our human experience, but more conservative people see the humanizing of women as a political thing that they disagree with and would like to legislate to suppress.

JC: Do you think that poems are political?

AC: Yes, I think all poems, and even all forms of art, are political in some way. I always tell my students that reading is an empathizing process, and we cannot be good critical thinkers that pave a future or make decisions about the world without our sense of empathy sharpened. A poem about nature becomes political when it makes a reader feel protective over the environment. A poem about motherhood becomes political when it makes a reader understand the ways women’s labor has been made invisible and not given value. Even a poem designed only to make us escape this world with something funny or supernatural becomes political once we realize why we need this reprieve and what we need to get away from.

JC: When you first began publishing poetry, did you ever struggle with the feeling of hyper-visibility? If so, do you have any advice for young poets who are scared of baring themselves to the public?

AC: No, never. I’m a poet, so I mostly feel invisible! (That’s a joke, but it’s also kind of true). Honestly, the things I write are the things that I feel unable to express and that I deeply want to be heard. I have always been more articulate through writing than I am through speaking, and that has always hindered my ability to communicate. I have also needed the page as a place to process the world around me. And, as a woman, my very existence feels like it’s something that’s, at worst, deeply hated, and at best, trivialized or objectified. I wanted to write because I wanted to process and have a voice, not be drowned out by the injustices in the world, whether those injustices were directed at me or others.

That said, a good amount of my writing is pretty personal, and I get this question a lot. I never know how to answer it: I guess I have no shame? I was always influenced by people like Sylvia Plath, Sharon Olds, and Anne Sexton, so the idea of shame was trained out of me. As a reader, I get the most out of radical honesty, so I’d tell young poets to think of the impact that this kind of writing can have on an audience and weigh if that impact is more important than their fear.

But I also don’t always write about myself, and I don’t think writers have to. We need poetry of witness now more than ever. If baring yourself feels traumatic or if you aren’t ready to do it just yet, then there are so many other creative pursuits to give your talents to in poetry.

JC: What’s next for you?

AC: I have a collaborative collection of spell poems written with Jenny Sadre-Orafai called Book of Levitations that comes out next summer with Trembling Pillow Press. I finished a book about my experience in Palestine called Graveyard of Numbers, and I am currently looking for a press to publish that. I did a peace delegation to Cuba and I’m going to Nicaragua in August to continue my research about U.S. policies and their damage to Latin American countries: this research serves my current creative project, which examines the effects of capitalism in America and abroad and responds to our current political situation: the book is tentatively titled When the Flag Becomes a Shroud.

**

Anne Champion is the author of The Good Girl is Always a Ghost (Black Lawrence Press, 2018), Reluctant Mistress (Gold Wake Press, 2013), Book of Levitations (Trembling Pillow Press, 2019), and The Dark Length Home (Noctuary Press, 2017). Her poems have appeared in Verse Daily, Prairie Schooner, Salamander, Crab Orchard Review, Epiphany Magazine, The Pinch, The Greensboro Review, New South, and elsewhere. She was an 2009 Academy of American Poet’s Prize recipient, a Barbara Deming Memorial grant recipient, a 2015 Best of the Net winner, and a Pushcart Prize nominee.

She holds degrees in Behavioral Psychology and Creative Writing from Western Michigan University and an MFA in Poetry from Emerson College. She currently teaches writing and literature at Wheelock College in Boston, MA.

Jeffrey Ricker‘s stories and essays have appeared in anthologies and magazines including Foglifter, Phoebe, Little Fiction, The Citron Review, UNBUILD walls, and others. A 2014 Lambda Literary Fellow and recipient of a 2015 Vermont Studio Center residency, he has an MFA in creative writing from the University of British Columbia. He lives in St. Louis.

Jeffrey Ricker‘s stories and essays have appeared in anthologies and magazines including Foglifter, Phoebe, Little Fiction, The Citron Review, UNBUILD walls, and others. A 2014 Lambda Literary Fellow and recipient of a 2015 Vermont Studio Center residency, he has an MFA in creative writing from the University of British Columbia. He lives in St. Louis.

Madeline Anthes is an ex-Clevelander living on the east coast. She is the acquisitions editor for Hypertrophic Literary and her writing can be found in journals like WhiskeyPaper, Lost Balloon, Cease, Cows, and Jellyfish Review. You can find her on Twitter at @maddieanthes, and find more of her work at

Madeline Anthes is an ex-Clevelander living on the east coast. She is the acquisitions editor for Hypertrophic Literary and her writing can be found in journals like WhiskeyPaper, Lost Balloon, Cease, Cows, and Jellyfish Review. You can find her on Twitter at @maddieanthes, and find more of her work at  Joshua Jones lives in Maryland where he works as an animator. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in CRAFT, The Cincinnati Review, Pidgeonholes, Split Lip Magazine, Monkeybicycle, SmokeLong Quarterly, Necessary Fiction, and elsewhere. Find him on Twitter @jnjoneswriter.

Joshua Jones lives in Maryland where he works as an animator. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in CRAFT, The Cincinnati Review, Pidgeonholes, Split Lip Magazine, Monkeybicycle, SmokeLong Quarterly, Necessary Fiction, and elsewhere. Find him on Twitter @jnjoneswriter. Midwestern Gothic staffer Henry Milek talked with author Amy Reichert about her book The Optimist’s Guide to Letting Go, mother-daughter relationships, optimism, & more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Henry Milek talked with author Amy Reichert about her book The Optimist’s Guide to Letting Go, mother-daughter relationships, optimism, & more.

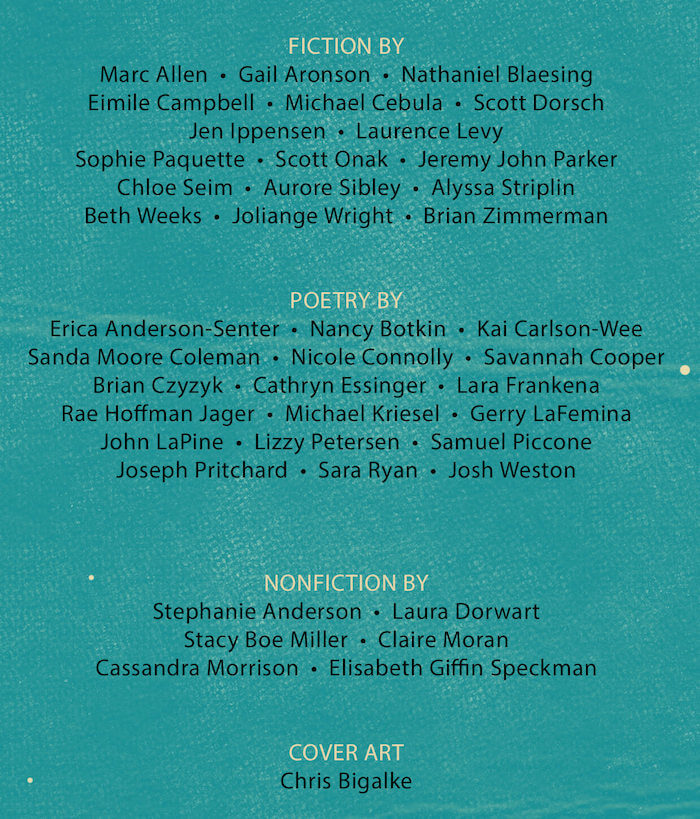

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ariel Everitt talked with author Julia Fine about her book What Should Be Wild, books that inspire her, self-empowerment, & more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ariel Everitt talked with author Julia Fine about her book What Should Be Wild, books that inspire her, self-empowerment, & more.

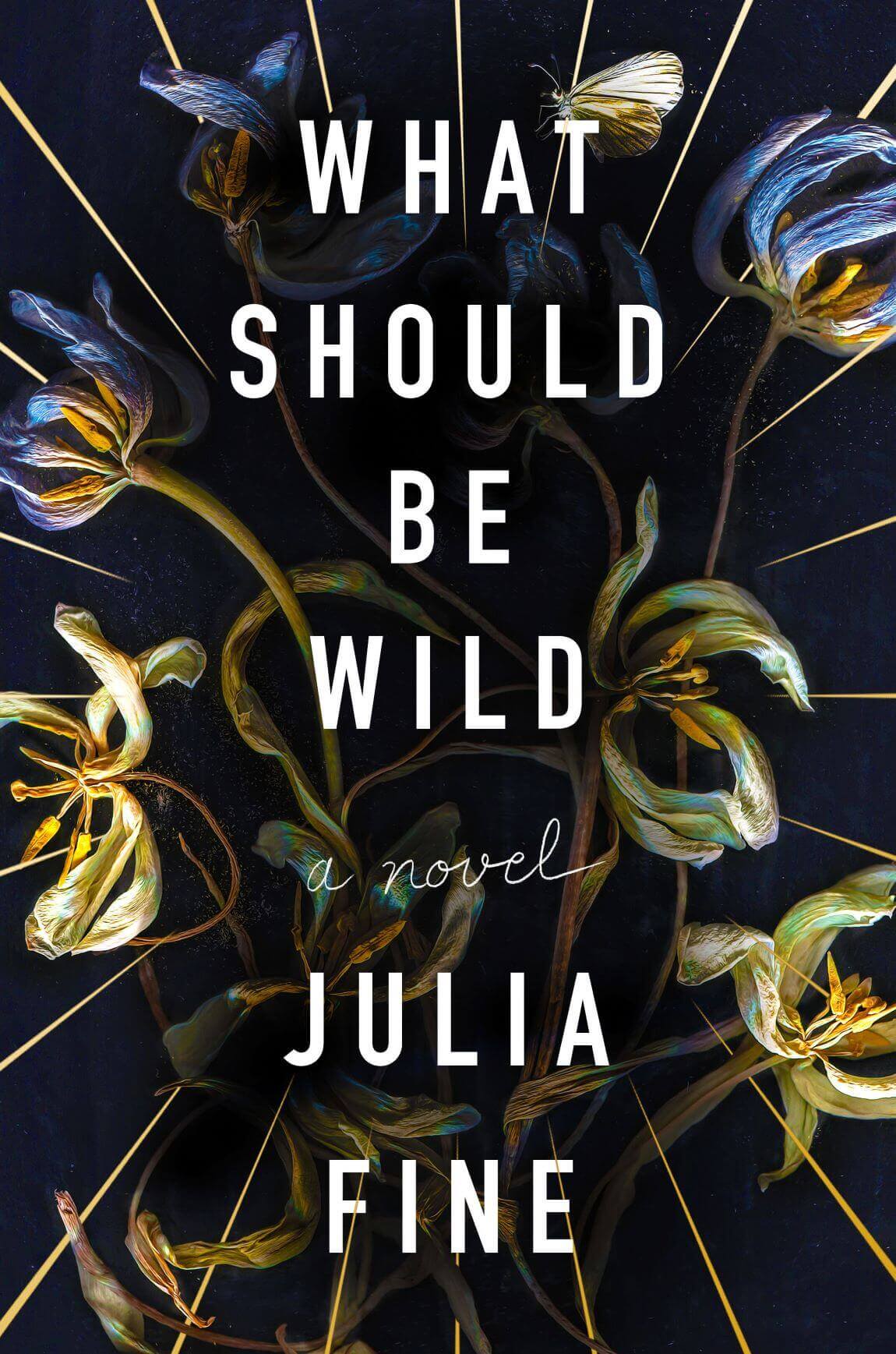

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with author Matthew Vollmer about his collection Permanent Exhibit, editing being an exercise in curation, writing for an audience in real-time, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with author Matthew Vollmer about his collection Permanent Exhibit, editing being an exercise in curation, writing for an audience in real-time, and more. JC: Could you say something about the title of the book, and what it means in relation to its message?

JC: Could you say something about the title of the book, and what it means in relation to its message?

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with poet Anne Champion about her collection The Good Girl is Always a Ghost, showcasing historically unknown women, politics in poetry, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with poet Anne Champion about her collection The Good Girl is Always a Ghost, showcasing historically unknown women, politics in poetry, and more.