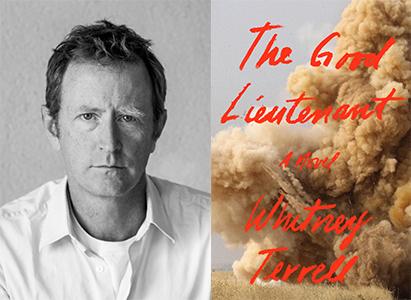

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Whitney Terrell about his novel The Good Lieutenant, re-structuring his novel into reverse chronological order, writing from a military-woman’s perspective, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Whitney Terrell about his novel The Good Lieutenant, re-structuring his novel into reverse chronological order, writing from a military-woman’s perspective, and more.

**

Lauren Stachew: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Whitney Terrell: I was born and raised in Kansas City. My family has been living here since the 1890s, on my mom’s side. And that side of the family moved here from Nebraska so . . . I think it’s safe to say that we are not a coastal family. On my dad’s side, his father grew up in Holton, Kansas, fought in WWI, went to law school at Kansas University and then moved to KC.

LS: Apart from living in the East Coast while attending Princeton University, you grew up and have lived most of your life in Kansas City. How did briefly living in a different region of the U.S. affect your conception of the Midwest?

WT: Like many young writers, I had an excessively romantic view of the East Coast, and New York City in particular. I thought of the Midwest as a place I needed to escape. Going to Princeton as an undergraduate did nothing to dispel this. What did change my conception of the Midwest was moving to New York after graduate school in 1996. I was pretty broke. I had a small shotgun apartment on E. 13th Street—an area that wasn’t yet as gentrified as it is today. I was fact-checking for The New York Observer. I liked living in the city. Loved it, really. I could feel myself being absorbed into its routines.

At the same time, in the mornings before I went to work, I began writing for the first time in my life about Kansas City. These were the opening pages of The Huntsman. On 13th Street, the world I’d left sounded exotic. Nobody there knew what it was like to build a raft and float down the Missouri River, as I’d done when I was sixteen. Nobody there had smelled the inside of a gas-lit hunt club. After fact-checking other people’s writing during the day, I began to look forward to imagining Kansas City in my own words. The feelings, smells, faces, voices, accents, streets, trees, and people of that city—and my awareness of the city over time—that was my material. That was what made me unique. I didn’t realize this until I lived on lucky 13th Street.

LS: Both of your previous novels, The Huntsman and The King of Kings County, address issues of race: the former centers on a young African American who finds his way into Kansas City’s white, upper-class society while searching for answers about his family’s past, and the latter focuses on the relationship between real estate and race in Kansas City. What made you interested in exploring this topic in your novels?

WT: The person I have to thank for that is James Alan McPherson. He was one of my professors at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and he was an incredibly powerful influence, a deeply caring, thoughtful, and generous mentor—at a time when I really needed a mentor like that. At Iowa, I was writing about Alaska, where I’d spend summers working on seine boats, fishing for salmon. McPherson was encouraging about that book. But in the end, his seminars and his lectures were more important. He was intensely interested in race. We read and discussed all the greats: Ralph Ellison—particularly the essays—Richard Wright, Toni Morrison, Dubois, Walker, Hughes and many, many more. (I’d include McPherson’s own work on this list, though he never did.)

McPherson also insisted that white writers had a responsibility to engage with the subject of race in their own work. He called it the “great American subject.” I can remember a terrific lecture he gave on Melville’s “Benito Cereno,” for example. This had a profound influence on me. Also, his way of talking about race was helpful. He was funny. He teased. He questioned. He was an iconoclast. He led his classes through a never-ending seminar on America’s historical and ongoing attempt to grapple with race and diversity. I took to heart his assertion that, as a white writer, these issues were part of my heritage too. Something I had a responsibility to engage with. Kansas City only became an interesting place for me to write about when I began to view it through this lens. In the 1990s and early 2000s, as I was writing The Huntsman and The King of Kings County, Kansas City and other northern and Midwestern cities like it were basically operating like apartheid states, long after the civil rights era had passed. People in the African-American communities of those cities were well aware of this. So were other writers. But it wasn’t part of our national conversation. It was a buried story—one of many.

For instance, The King of Kings County focuses on how real estate companies used racial covenants to segregate Kansas City. I discovered as I did my research that many people knew about this, but it had been kept out of the official histories of the companies involved—and omitted from the city’s history generally. I wanted to force this history into view, make it visible in narratives that people couldn’t ignore. For a long time, I felt like I’d failed. The books were well reviewed, but outside of Kansas City, maybe, I didn’t feel like they had much effect. Now, after Ferguson, and Baltimore, and Chicago—the painfully long list of cities where we’ve seen protests—these kinds of stories are in focus. People are paying attention. Excellent new books are being published. My students talk about these issues. It’s insane that it has required more than two years of protests, in cities across the country, and the deaths of numerous unarmed black citizens at the hands of the police to get mainstream America, and especially white America, to make this a part of our national conversation. But I’m not surprised. Resistance movements like Black Lives Matter are responding to a deeply seated structural racism that the residents of all these cities had known about for decades. I knew about it. Thanks to McPherson, I was able to write about it in those early novels. The subject has only become more and more urgent. I hope people will revisit those books now.

[Note: James Alan McPherson died this past summer, after this interview was completed. A number of his former students wrote about their memories of him on literary sites and on social media. I wrote my own piece for Literary Hub, which you can find here: http://lithub.com/obama-america-and-the-legacy-of-james-alan-mcpherson/]

LS: Your most recent novel, The Good Lieutenant, opens with a failed Army operation in Iraq led by the main character, Lt. Emma Fowler, and from this point the narrative moves in reverse chronological order. How did you arrive at this structure? Did you always intend for the novel to operate this way?

WT: I wrote the novel in chronological order originally. Never considered going backward. My current editor, Sean McDonald, read the book in that original form. He told me, “Look, the last hundred or hundred and fifty pages of this are good. You just need to get to them more quickly.” The book was over three hundred pages long at the time. Even so, I was fine with his suggestion. I was just glad that an editor thought that there was some part of the book that was worthwhile because by then, I’d been working on it for about six years and still wasn’t happy with it.

So I cut the beginning. I tried to write something new that could be grafted on to those 150 good pages. But it seemed like no matter what I tried, I couldn’t gain any momentum. These scenes were boring, slow, and clunky. I worked at this for six or eight months until finally I realized I just couldn’t do it. Here was this terrific editor—I’d known about Sean for years and really respected the writers he published—who was interested in this book, and had given me this completely reasonable suggestion to fix it, and I was still going to fail. I was sitting right here at my desk on the day that I gave up. It was a beautiful spring day. I was miserable. I had selected the last forty pages of the novel and was trying to imagine how I might be able to turn them into a short story, so I could at least get something out of this project. But no luck. Even in that shortened form, I realized that the ending of the novel was too narrow, too deterministic, too negative. The message was, in essence, “Hey, look, the war turned this woman’s life into a mess.” Not a very original idea. The various chapters of the book were spread around me in a mess. I kept paging through that last scene, hoping to find a way to save it. Somehow, a scene from earlier in the book got mixed in underneath those final pages. When I arrived at it, I actually had an idea. A very rare moment of inspiration. I realized that if I told the story in reverse, the ending wouldn’t be so narrow. Instead, the characters would grow and complicate themselves as they moved away from combat. The novel would have that crucial feeling of expanding outward—without giving up my belief that war is not, in fact, an avenue for character growth.

LS: In 2006 and 2010, you embedded with the U.S. Army in Iraq and covered the war for The Washington Post Magazine, Slate, and NPR. How much of this experience inspired or informed the story and characters in The Good Lieutenant?

WT: Those experiences were crucial. Especially the embed in 2006. In my mind, that’s roughly when the book takes place—though I don’t specify a year in the text. I’ve always been a really place-oriented writer. So just on a basic level, it was extremely important for me to be present in that physical space. Sensory inputs are irreplaceable. What does an Iraqi shopping center look like? What do the road signs say? What’s on TV? I remember attending this one, extremely long meeting at a schoolhouse out in the countryside, outside the wire. The lieutenant colonel from the battalion I’d embedded with wanted to meet with a group of local sheikhs to try to convince them to stop letting insurgents travel through their neighborhood. The text of the conversation is one thing—I have that in my notes. It tells you that neither the sheikhs nor the colonel were fully in control of their territory. They needed each other’s help but didn’t trust each other. They were still trying to figure out what was causing the uptick in violence they were seeing in that area. (The answer was that we were witnessing the beginning of a civil war between the Sh’ia and the Sunnis in that area. But this was only clear in retrospect.)

So that would be the “story” in a journalistic sense. But as a novelist, there are so many other things to see. How the sheikhs dress, the kinds of cigarettes they smoke, the soda they drink, the cell phones they use. There’s a donkey tied up in back of the schoolhouse, braying the whole time. There’s the colonel’s interpreter, wearing an Iraqi Army flag on his shoulder, looking smug and disdainful as he translates what he believes to be yet another digression from one of these sheikhs. Or giving one word translations when the guy has just shouted for several paragraphs. There are the empty cubbies used by the children who have class in that school room. Chalk boards. Kids’ drawings on the walls. A map of the world with the Middle East in the center of the page, just as our world maps at home put America in the center. A bunch of open paint tins stashed in the corner, with the brushes still stuck inside them, as if somebody had just painted the walls of the school room in preparation for the U.S. colonel’s visit. Or maybe they had painted over something they didn’t want the colonel to see.

So yes. It was important.

LS: Was it a conscious choice to have a female frontline officer in this novel? Writing from a male perspective, did you receive any criticism for this decision?

WT: Emma Fowler was the protagonist of this novel from the beginning—even before I ever went to Iraq. I never once imagined the novel as being about anybody else. I knew only a few basic things about her. I knew that she’d been in ROTC and that her mother had left the family when Emma was a young girl, and that Emma had grown up having to care for her brother as a kind of replacement mother. I knew that, as an officer, at least in the beginning of her career, she was a very rule-oriented person. Very much about toeing the line, following procedure, and that she took comfort in that—and that this specific aspect of her character would be challenged as her time in the Army and her time in Iraq progressed. That was it, in terms of facts. I did, however, have this internal, instinctive feeling about what kind of person Emma was. For a long time, this was just a feeling. I could say to myself, “Well, she would react this way in this kind of situation.” Or, “That doesn’t sound like something she’d say.”

The long process of writing the book was in part a process of developing a fully coherent, explicit understanding of this instinctive feeling. Why did Emma care so much about following procedure? How did her past inform her present? What was her ethic?

As for why I chose a female character, it’s honestly difficult to remember with any clarity. It feels like I wanted to write about Emma Fowler specifically. Not just a generic “female officer.” The best I can say is that I knew women were serving in Iraq and Afghanistan in unprecedented numbers. This seemed interesting on its face. And I think it’s always useful, when you are writing about an institution like, say, the Army, to have a character who is part of that institution but at the same time separated from it. And outsider. Draftees played this role in a lot of previous war novels—but of course there were no draftees in Iraq.

So those considerations may have played a role. What I can say, with absolute certainty, is that once I started interviewing and meeting with female soldiers, in Iraq and in the States, I became immediately aware that their stories were fascinating. Their stories were also different than any war story I’d ever read or seen. And beyond that, they felt that their stories weren’t being told. Fortunately, that is changing. Authors like Helen Thorpe, Kristen Holmstedt, Helen Benedict, Kayla Williams, Odie Lindsay, and Cara Hoffman have also published books that address the experiences of female soldiers. I know several female veterans like Teresa Fazio and my former student, Anne Kniggendorf, who are working on books about their military experience. They should be published too. If I can, I hope to help with that. As for the last part of the question, the most gratifying part of this process has been showing the novel to the women who consulted with me on it. Asking them to read it. Talking to them about it afterward. Having them say, “Yes, the book gets this right.”

To me, The Good Lieutenant is a collaborative work, more than anything I’ve ever written. I couldn’t have done it on my own. Women like Major Stacy Moore, former Sergeant Angela Fitle, and Lieutenant Colonel Jen McDonough, all of whom consulted on the book, are its authors too. So are the male soldiers I embedded with like former Captain Nate Rawlings, and Sergeant Travis Parker. I’ve been lucky enough to do events with them on tour, let them talk about their own experiences in person. You can find recordings of these events and interviews on the FSG blog Work in Progress, at New Letters on the Air, and at the Politics & Prose website.

LS: You’ve taught at the University of Missouri-Kansas City since 2004. Is there a piece of advice you always give your students?

WT: Write every day, if possible. Repetitive effort is the best way to solve problems. Try to keep your schedule as clear as possible. Okay, you’ve got to teach, or do whatever’s necessary to pay the rent. Do that. But otherwise, keep your overhead low. Don’t sign up for extra classes in an effort to hurry up and get your degree. Try not to fill your schedule with extracurricular activities. Leave your days open. Dealing with the pressure that open, unscheduled writing time presents is crucial to becoming a writer. An MFA program should be a protected place that is designed to provide you with that kind of time. You should think of this unscheduled time as the most important class you’ll take. You, alone in a room, with nothing to do but write. It takes a long time to get used to living that way. School is where that process begins.

LS: What does a typical day of writing look like for you? Do you have a certain routine or schedule that you stick with?

WT: I drive one of my sons to school and am back at my desk by 8:30. I generally work until 3:00 or 4:00. I go for a run. I eat dinner with my family. I grade papers at night. Rinse, repeat.

LS: What’s next for you?

WT: I’m on a flight to Pittsburg, where I’m excited to do an event with an Iraqi poet, Sabreen Kadhim, at City of Asylum. More generally, another Kansas City novel will be next. I’ve started on it.

**

Whitney Terrell is the author of The Huntsman, a New York Times notable book, and The King of Kings County. He is the recipient of a James A. Michener-Copernicus Society Award and a Hodder Fellowship from Princeton University’s Lewis Center for the Arts. He was an embedded reporter in Iraq during 2006 and 2010 and covered the war for the Washington Post Magazine, Slate, and NPR. His nonfiction has additionally appeared in The New York Times, Harper’s, The New York Observer, The Kansas City Star, and other publications. He teaches creative writing at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and lives nearby with his family.

Eric Shonkwiler’s bold second novel 8th Street Power & Light is here for your fall reading pleasure!

Eric Shonkwiler’s bold second novel 8th Street Power & Light is here for your fall reading pleasure!

Christine Rhein’s piece “Baptism by Assembly Plant” appears in

Christine Rhein’s piece “Baptism by Assembly Plant” appears in

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Amy Hassinger about her book After the Dam, learning through teaching, commonalities between environment and motherhood & more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Amy Hassinger about her book After the Dam, learning through teaching, commonalities between environment and motherhood & more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Whitney Terrell about his novel The Good Lieutenant, re-structuring his novel into reverse chronological order, writing from a military-woman’s perspective, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Whitney Terrell about his novel The Good Lieutenant, re-structuring his novel into reverse chronological order, writing from a military-woman’s perspective, and more. Tracy Harris’s piece “T for Tiberius, Twice is Not Enough” appears in

Tracy Harris’s piece “T for Tiberius, Twice is Not Enough” appears in

Alec Osthoff’s story “The Tomb of the Pharaoh” appears in

Alec Osthoff’s story “The Tomb of the Pharaoh” appears in