Kali VanBaale, whose novel The Good Divide was released earlier this week, was recently interviewed by Donald Quist at Fiction Writers Review:

Kali’s voice has stayed with me since the day I reached for her suitcase, and it continues to motivate my own writing. Through my friendship with Kali VanBaale, I have learned a lot about labor, love, and persistence. And, I have benefitted from her insights on publishing and craft.

Kali’s prose bares her unique cadence, featuring compassionate narratives that challenge misconceptions about motherhood, matrimony, and the American Midwest.

Read the full interview here.

Shop for The Good Divide here.

June 16th, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author John Jodzio about his short story collection Knockout, reconciling shockingness and logic, the satisfaction of performing his work, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author John Jodzio about his short story collection Knockout, reconciling shockingness and logic, the satisfaction of performing his work, and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

John Jodzio: I was born in Chicago and grew up in Minnesota in a small town with a population of 2,000. I’ve lived in Minneapolis most of my adult life. Unless there’s some apocalyptic event where every one of the 10,000 lakes in Minnesota dies, I’m probably here for the duration.

GE: Your new short story collection, Knockout, is full of dark humor and seedy characters. What inspires you to write about them?

JJ: I don’t know if I’m ever really thinking of my characters as seedy when I start writing about them, but for some reason they usually end up there. In the end, I’m really drawn to weirdos and people living off their wits – probably because my real life is pretty fucking boring.

GE: The stories in Knockout are somewhat shocking, from a guy stealing a tiger to sell for meth to a man buying a used sex chair from his neighbor. How do you go about writing these somewhat wild stories while still making them seem logical within the frame of the story?

JJ: I’ve found that when you have shocking stuff happening in a story you had best balance it with a matter-of-fact tone and some strict-ass realism. I think it also helps that all of the things I write about could actually happen in the real world, even though they probably never ever will.

GE: Are any of them based on real life events? Do you draw your inspiration from specific sources?

JJ: Most of my stuff comes directly from my imagination. Any of the real stuff is usually bits and pieces of things I glue together to make a story more fun or interesting. For example, Jayhole, the horrible bounty hunting/scrapbooking roommate in the story “Duplex”, is an amalgam of all the bad roommates I’ve ever had.

GE: You have written two other books of short stories, Get In if You Want to Live and If You Lived Here You’d Already Be Home. What is the process like creating a collection of short stories? How do you know when you are done? Is it difficult deciding which stories should appear in a collection together?

JJ: I think other people probably have a much more complicated or smart way of doing this, but generally I’ve always just waited until I get about 150-200 pages of really good work and then I’ve put things in an order I think fits. I have a pretty consistent tone/voice so my stories seem to fit together decently even if the subject matter varies.

GE: You have a great video of yourself reading aloud “I Came to This Orgy to Honor My Pet Snake, Tito” for Button Poetry. Does reading your stories aloud change them at all? Do you enjoy performing your work?

JJ: I enjoy it a lot — my work tends to be pretty funny and has scandalous moments in it, it’s usually fun to read for a crowd. Especially crowds that have a couple of vodka sours in them.

GE: Do you have any authors that inspire you?

JJ: There are tons. Lindsay Hunter, author of Ugly Girls, Don’t Kiss Me, is fucking amazing. Love, love, loved Catherine Lacey’s last book, Nobody Is Ever Missing. Obviously I’m a huge fanboy of George Saunders. J. Ryan Stradal’s book, Kitchens of the Great Midwest, if you haven’t already read it, is incredible. Some others inspirers = David Sedaris, Miranda July, Diane Cook, Adam Johnson.

GE: What’s next for you?

JJ: I’m at work on a novel now. It’s about a reluctant detective with a missing upper lip and a laughing gas. It is kind of an exciting mess right now. The last sentence I wrote for it is: “Tommy is a better drug lord than the other drug lords in our town because he only makes us swallow ten regular size condoms instead of ten extra large ones.” Stay tuned.

**

John Jodzio‘s work has been featured in a variety of places including This American Life, McSweeney’s, and One Story. He’s the author of the short story collections, Knockout (Soft Skull Press, Spring 2016), Get In If You Want To Live and If You Lived Here You’d Already Be Home. He lives in Minneapolis.

June 16th, 2016 |

Kali VanBaale, whose novel The Good Divide was released yesterday, was recently reviewed by Corinne Gould at Ooligan Press:

It’s easier to notice small details—the sounds of nature, the rhythms of a household, the intimate interactions between people—with little noise or distraction, and so I worked hard to try and capture that hyperfocus in a way that felt relevant to the story and natural for my main character. And Jean is also an outsider looking in, doomed to only observe her heart’s greatest desire, so she’s constantly tuned in to the finest details.

Read the full interview here.

Shop for The Good Divide here.

June 15th, 2016 |

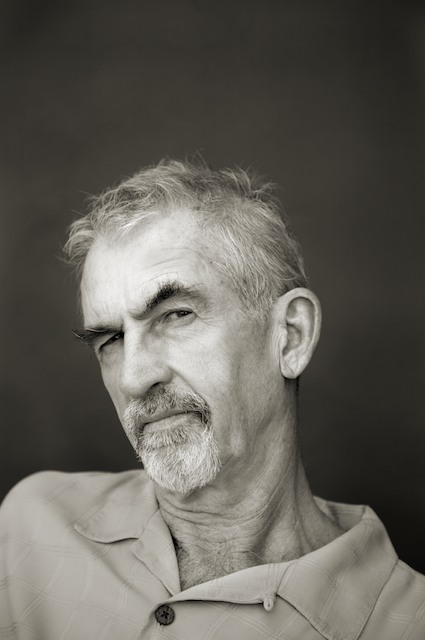

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with author Peter Geye about his new book Wintering, the evolution of his writing process, choosing the right narrator and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with author Peter Geye about his new book Wintering, the evolution of his writing process, choosing the right narrator and more.

**

Rachel Hurwitz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Peter Geye: I was born and raised in Minneapolis, and with the exception of a year being a ski bum in Colorado and three years at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, I’ve lived here my whole life. Two of my children were born in the same hospital I was. So my roots here are pretty deep and native. And I love this.

But I believe there’s more to my connection than simply having come and lived in this place. I think of it in what can only be described as parallel ways. I’m no biologist, but I understand that most animals thrive in an ecosystem particular to their physiology. Minnesota has its share of these animals — moose, wolves, lynx — and I simply count myself among these beasts. This place is my natural habitat. I’ve evolved to love it, and thrive here. The other line running parallel to this is a little less scientific, and I can only think of it like this: I have a psychic connection to the place I’m from. So much of my identity is marked by this landscape, by the seasons, by the water.

To say this part of me is what drives my writing would be an understatement. Where some folks might talk about how they conceive of their characters, I think of how my characters conceive of me. I learn more about the world from them than I ever could ascribe to them. Which is another way of talking about the way my psychic connection to Minnesota and the Midwest is a part of my daily life.

RH: You spent some time as a professor at the Creative Writing program at Western Michigan University. What do you think this experience taught you about your own writing, or writing in general?

PG: I taught at Western, but was never a professor there. In fact, I was a student. But still, my years at that university were extremely informative. I read voraciously while studying there. And I wrote a lot about what I read, which required me to think deeply. Of course, reading and thinking about it were two things that I already did with quite a lot of frequency (I have an English degree from the University of Minnesota, and an MFA from the University of New Orleans), but something about studying for a PhD required me to take my thinking to the next level. This in turn taught me to think about my own work in ways I might not otherwise have ever been able to. For that I’m everlastingly grateful.

But I also taught at Western, and this was an equal part of my education. If my studies were teaching me how to read critically, my teaching was showing me how to read empathetically, which is indeed the more important part of the transaction between writer and reader. Academia is, to my mind, essential. But the more essential — I might even say most essential — part of why we read and write is to find commonalities with each other. I learned most of what I know about that teaching undergraduates how to be honest with themselves — how to tell their stories honestly — and for this I’m always grateful.

RH: Are there any necessities in your writing process — such as being in a certain location, using a specific type of pen or creating an outline beforehand?

PG: There used to be! While I was writing my first novel (Safe from the Sea) now some fifteen years ago, I required absolute silence and absolute darkness. Every night I would make a pot of coffee at nine or ten and adjourn to my little office with my certain pens and notebooks. If the house creaked or the wind blew too hard, I lost my mind. It’s crazy to think about that, because by the time that book was published about six years ago, I had three kids, and the closest I got to silence was when only two of them were crying.

My second and third books were written in coffee shops and at the kitchen table, often with one hand in the peanut butter jar. I write on bar napkins and on post-it notes and when such a thing as quiet time exists, in my notebooks. Some things I outline and some things I don’t. Sometimes I work for eight hours a day, sometimes for eight minutes. Many days I don’t work at all.

What’s important to me now — what is indeed essential — is that I’m fully in love with my characters. That I treat them like I do the people closest to me. And of course, that I always remember what I’m really working toward is introducing these people and their lives to readers, so that I should be careful to make that meaningful when it happens.

RH: Your latest novel, Wintering, follows Gus, whose father has just been pronounced dead after disappearing from his sickbed, retelling the story of how he and his father had vanished into the Minnesota wilderness thirty years earlier to a close family friend, Berit. Where did the idea for this story arise?

PG: I’ve been traveling to the part of Minnesota and Canada described in this book since I was a young boy, and from my earliest memories of this wilderness, I’ve been aware of how easy it would be to disappear (or to make someone disappear) there. I mean, we’re talking about almost two hundred thousand acres of utter wilderness. A place with nothing but trees and water and the occasional fellow canoeist. It’s a perfect place to set a story, especially a story about getting lost and found, and about retribution of a violent sort.

On top of all this, it’s just quite simply the most beautiful place I’ve ever been. This beauty makes me want to describe it, to show it to those in the world unlucky enough to have never been there. That’s a not small part of my ambition with all of the books I’ve written — to show people this place I call home.

RH: What made you chose to start the novel from Berit’s point of view? What do you think her opinion and voice brings to the opening of the novel?

PG: I spent so many hours toiling over who ought to tell this story. Honest to god, I must have written the first fifty or a hundred pages of this book half a dozen times. I knew I wanted it to be told from a woman’s point of view. I’m comfortable writing in the voice of a woman for all sorts of reasons, but for this particular story I wanted there to be a sort of counter-balance to the masculine part of the story that takes place in the woods. I also knew I wanted the voice to be laconic and reflective and for the character who owned the voice to have a long view. I tried writing it from Gus’s wife’s point of view, and from his daughter’s, and from a few other versions of women like Berit. But none of them really accomplished what I wanted the voice to do.

And then Berit came along. The first scene I saw her in was when she’s a young woman, having just arrived in town to work for the mad hatter, Rebekah Grimm. Berit is on the shore picking flowers and she meets Harry, and as soon as they started talking to each other, I knew she was my voice. I felt so much like her. I understood her so instinctively. Those are a couple of pretty good barometers for me. And I was right about her. She impressed me every day, and I continue to live very happily with the memory of her.

RH: The beautiful and brutal setting of a cold winter in the river-filled woods of Minnesota plays a huge role in the plot and power of this novel. Why did you choose the town of Gunflint and the backwoods of Minnesota rather than any other span of wilderness?

PG: The short answer is that it’s a territory I’ve known my whole life. I was ten or eleven the first time I went into the Boundary Waters, and much younger than that the first time I visited Lake Superior. For all the places in the world I’ve traveled, I still prefer this cold and quiet place. And this might be reason enough to choose it as a location for my fiction, but it has another quality that bears mentioning. If I’ve been up there a hundred times in my life, I’ve never seen it the same twice. Between its temperamental weather and seasons, and a landscape that seems to be evolving in real time, the mood and light and way this area feels is never redundant. It’s a new world every day. And this is a tremendous ingredient for fiction. The nature of this place — of its changeability — well, it makes the characters who inhabit it seem larger and more complicated. This, above maybe all other qualities, is what I love about it.

RH: Wintering, like your other novels Safe From the Sea and The Lighthouse Road, seem to grapple with the relationships between generations of family members. How does this theme resonate with you and why is it prominent in your work?

PG: I wish I had a good answer for this question. I mean, on the one hand, I’ve always been interested in my family’s past. But by the same token, I’ve not once visited any of the ancestry websites. Perhaps there’s a part of me that would rather just imagine their lives. And maybe that wonder is what drives me to write about families and their long pasts in my novels.

When I wrote Safe from the Sea, I did so from the point of view of a son. I was confronting the relationship from my role as my father’s child. In the Eide family books, it’s been more from the point of view of the parent. I guess this is natural, since I went from being a son to being a father and son. But now when I think of these relationships, they’re much more complicated and daunting, and one of the best ways to make sense of them is to take the long view. To consider hundred year old blood as meaningful even now. It’s almost cosmic, to my way of thinking. And certainly this consideration has become a preoccupation for me. In my life and in my work. And I’m likely to keep on exploring it, knowing, of course, that I probably won’t find any satisfactory answers.

RH: What author or individual has had the greatest influence on yourself and your work — either literary or personally?

PG: Well, no doubt my family has had the greatest influence on me. Both in terms of my daily life and my work. But that’s probably not the answer you’re looking for.

With respect to folks who have influenced me, there’s a long list. First there was my high school English teacher, Dave Beenken, who turned me onto the joy of reading and the idea that a book could be a pleasure. The first books he showed me were Hemingway’s — A Farewell to Arms, the stories, For Whom the Bell Tolls — and I still count them as essential, even as out of vogue as they’ve become. Find me a story I like more than “Big Two-Hearted River” and a wonderful story it will be. After Hemingway came a whole flood of American novelists. Willa Cather. Zora Neale Hurston. Alice Walker. William Faulkner. Toni Morrison. Thomas Wolfe. Then a bunch of Russian novelists. Then several courses in Scandinavian literature. Ibsen, Strindberg, Vesaas, Hamsun, Lagerkvist. I went through a period of time when I read an awful lot of Henry Miller. I thought it was sexy and exotic and I liked the idea of living the sort of life he recorded. But I haven’t read Henry Miller in twenty years. I read Philip Roth with a lot of pleasure, and because he recommended her, I’ve read most (if not all) of Louise Erdrich’s novels and stories. She’s a national treasure, and another person who calls the Midwest home. And all of this reading was, I like to think, a kind of preparation for the books I count among my very favorites. These include Gil Adamson’s The Outlander, Annie Dillard’s The Living, John Casey’s Spartina, Robert Stone’s Outerbridge Reach, Annie Proulx’s Postcards, Amy Greene’s Long Man, Danielle Sosin’s The Long-Shining Waters, Ben Percy’s The Wilding, Richard Russo’s Empire Falls. And my favorite novelists, Kent Haruf and Cormac McCarthy and Joseph Boyden.

It would be ridiculous not to mention my teachers, also. Jaimy Gordon, Stu Dybek, Patricia Hampl, Richard Katrovas. And my editors, two of the all-time best: Greg Michalson and Gary Fisketjon.

All of these books and people have influenced me in ways I could never begin to measure. Still, I can say that every single one of them has been instrumental. Looking at this list is a pretty great reminder that writers don’t do everything in isolation. I’ve been surrounded by so many great influences, and my work wouldn’t exist without all of them.

RH: What’s next for you?

PG: For the first time in my life I’m working on two projects simultaneously. The first is a book of non-fiction called Laurentide. It’s a book about my relationship with the North Shore of Lake Superior, about time and memory, about being a father, about being vulnerable to life’s vicissitudes. It’s a book about writing.

I’m also hard at work on another novel of the Eide family, the last of this trilogy. It’s called Northernmost and it takes place in Gunflint, of course, but also goes back to Norway. It’s about marriage and longing. It’s an Arctic survival story. It’s a story about fathers and daughters. It’s about love, losing it and finding it again when you least expect it, when you’ve given up on it, when you’ve stopped dreaming about it, in one deep breath.

**

Peter Geye is the award winning author of Safe From the Sea, soon to be a major motion picture, The Lighthouse Road, which was a World Book Night 2014 selection, and Wintering, just published by Knopf. He holds an MFA from the University of New Orleans and a PhD from Western Michigan University, where he was editor of Third Coast. He was born and raised in Minneapolis, where he still lives.

June 9th, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Sofia Samatar about her novel The Winged Histories, concentrating on those without a voice, writing across different modes and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Sofia Samatar about her novel The Winged Histories, concentrating on those without a voice, writing across different modes and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Sofia Samatar: I was born in Goshen, Indiana and lived in Indiana and Illinois until I was seven. Then I moved around quite a bit – Tanzania, England, Kentucky, New Jersey – before coming back to the midwest for college and graduate school. I went to Goshen College and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Because I was born in the midwest and lived there during some important formative years, I’m very comfortable there.

GE: Your new novel, The Winged Histories, is a companion novel to your debut novel A Stranger in Olondria. How did you go about interlacing the two novels? Did you run into any obstacles setting a new story in the same world?

SS: I conceived the A Stranger in Olondria story as a two-book project from the beginning, and had a basic idea of how the two parts would connect and complement each other. I wrote the first draft of the whole project – both books – before trying to publish the first one, in order to preserve continuity. I was so scared that if I published A Stranger in Olondria before writing the second book, I’d run into problems, like I’d need to move to a town across a river or something, and the map would already be public! So even though the manuscript of The Winged Histories changed quite a bit, I did complete it before the first book came out. This is a good method for writing works set in the same world, although, of course, it takes a lot of patience.

GE: As opposed to A Stranger in Olondria, which follows one male lead, The Winged Histories follows four different characters, all women, with a section of the novel devoted to each. What inspired you to write the companion novel in this way? Was there something you wanted to say about women, their roles in this novel or in real life?

SS: Concentrating on women in the second book was a conscious choice. This is something that developed in the later drafts of The Winged Histories. As the theme of lost histories grew stronger, I began to focus on those who had not been able to tell their stories in the first book, and who are often dropped from history in our own world: women, LGBTQ people, colonized people, religious minorities. There is also a section that echoes a key part of A Stranger in Olondria, but in reverse: in A Stranger in Olondria, we receive a woman’s story, but it’s written down by a male hand, while in The Winged Histories a man’s story is written down by a woman.

GE: The Winged Histories deals largely with a fictional violent rebellion, with each character caught up with it in a different way. What process did you go through to be able to put yourself in the different shoes of each character and write their stories?

SS: I know Olondria well, so imagining the different landscapes and moments of the war wasn’t a problem – those feel very real to me. But each of the four sections has its own tone, and each character a different kind of music, so I needed to put myself into the right space to imagine each part. I did this through reading. Some people make playlists for their novels; I have booklists. To give you an example of some writers who haunt The Winged Histories: for Part One, W.G. Sebald and Miral al-Tahawy; Part Two, Leonid Tsypkin and Jean Rhys; Part Three, Carole Maso and Assia Djebar; Part Four, Anaïs Nin and Tolstoy.

GE: How did you first come up with the intricate world of these two novels? How do you keep all of the details straight while writing?

SS: I take notes! I have quite a few Olondria files – cities, legends, agriculture, genealogies, literary movements, etc. As for how I came up with it – like any fantasy, it’s built from elements found in the world I know. It’s especially influenced by places I’ve lived: Egypt and South Sudan. But its relationship to the real world is mysterious and oblique, like the relationship of a collage to its materials.

GE: Aside from novels, you’ve also written quite a few poems, short stories, and essays. Do you have a preferred mode of writing? When you first get an idea, how can you tell which mode of writing you will use to expand it? Is it always clear?

SS: I’m most drawn to the novel, because that’s mostly what I read. But I do love different types of writing. I like working with an idea in more than one form. Every chapter of my dissertation on the Sudanese writer Tayeb Salih, for example, also became a piece of fiction. The Sufism chapter went into a story called “A Brief History of Nonduality Studies;” the chapter on epic poetry became a section of The Winged Histories. Last year I wrote an essay about Charlie Parker called “Skin Feeling,” which also exists as a short story – and so on. Sometimes I can’t really tell what’s going on with form. Sometimes form just seems like a label, or something I can only talk about in the most boring way. When is something a poem and when is it a lyrical blog post? Yet I do care about form very much. In the end I like to know what to call my work.

GE: The shared setting of your two novels is intricate, fantastical, and entirely of your own creation. What has surprised you most about releasing this world out to the public? Is there a level of vulnerability that goes along with asking the reader to step into a world that you crafted entirely, as opposed to a story that takes place in our same world? Do responses for novels differ from essays, short stories, and poems?

SS: I think with a made-up world, the writer’s vulnerability is actually very slight. Who’s going to correct me on Olondrian geography? It’s harder with something set in our own world, and hardest of all when you reveal something about your own life, which I’ve been experimenting with lately.

The biggest publication surprise for me was definitely the attention A Stranger in Olondria got, the awards it won. I was such a newcomer. I was thrilled.

GE: What’s next for you?

SS: I’m working on a new book. It’s a hybrid text combining fiction, history, and memoir, based on a migration of Mennonites from Russia to Central Asia in the 1880s. In a way, it’s a real departure from what I’ve been doing, but in a way it’s a culmination of everything. It includes all the forms I love, and it meditates on some of the same themes as the Olondria books: borders, storytelling, empire, faith, and memory.

**

Sofia Samatar is the author of the novels A Stranger in Olondria (2013) and The Winged Histories (2016). Her work has received the John W. Campbell Award, the William L. Crawford Award, the British Fantasy Award, and the World Fantasy Award.

June 2nd, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with writer Travis Mulhauser about his novel Sweetgirl, humanity in easily-villainized characters, the redemption to be found in humor and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with writer Travis Mulhauser about his novel Sweetgirl, humanity in easily-villainized characters, the redemption to be found in humor and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Travis Multiuser: I’m from Petoskey, Michigan and lived in northern Michigan through my early twenties. My grandparents from both sides lived in the Detroit area, and much of my family is still found in the Mitten. I will always claim Michigan as my home, so far have stuck to northern Michigan in my fiction writing, and maintain relationships with friends from Michigan I’ve had my entire life. And if we’re being completely honest, my fandom for the Detroit Lions and Michigan State Spartans very much keeps me connected to the state and identifying as a Michigander. My kids, to this point, have maintained those rooting allegiances and it still strikes me as odd that they are actually from North Carolina and not Michigan.

GE: How does the setting of a small northern Michigan town, specifically in the winter, play a role in your new novel Sweetgirl? Why did you choose to set the story in that place?

TM: I write about northern Michigan because it’s the place I know the best, even though I’ve been in the south for some fifteen years. I think the landscape will always be interesting to me, in part because it’s beautiful and severe, and in part because its where I spent my formative years. They were also pre-Internet years and when I think of my childhood I feel like I spent an inordinate amount of time staring out of windows — in the backseat of my parent’s car, in school, at home — I just have that landscape stamped in my consciousness in a way that I don’t for other places I’ve lived and visited.

My mom used to go for drives. She’d take me, my brother and sister on these aimless cruises around town and all the “country roads.” We’d listen to her 8 tracks, I particularly remember Kenny Rogers’ “The Gambler” and a whole shitload of Neil Diamond and I’d just listen to the music and stare out and let my mind wander. It might not sound like it — I know people have strong feelings on both sides of the Neil Diamond debate — but it was actually pretty wonderful.

GE: Going along with the small town setting is an atmosphere of drug use. Do you see the drug culture, specifically meth, as being an unavoidable part of the landscape?

TM: Yes, for these characters. But like anywhere I feel like drugs can be found if you want to find them, and in most places, for most people, avoided if you’d prefer to stay away. I think Shelton is the type of guy that would always be able to locate a buzz — if he was stranded on a desert island it would probably take him less than a week to figure out how to extract some sort of syrup from an indigenous mineral, mix it into a powder and smoke it through a bamboo shoot to get blasted. Shelton will be a handful wherever he is and I think the small-town stuff — he rides snowmobiles instead of the subway — is secondary to that core element of his character.

GE: How did you go about creating the relationship between Percy, the main character, and her mother Carletta, a meth addict? Was it difficult to write about a meth addict mother and a child that cares nonetheless?

TM: It wasn’t difficult at all. In fact, of everything in the novel, I might have been most comfortable writing about Percy and her complicated feelings about her mother and her mother’s addiction. I have never thought of addiction or drug use as a moral failure. Ok, maybe I did when I was seven years old and the War on Drugs was being launched — a catastrophically stupid war, even by war’s standards — but the thing about “the enemy” in that war is that at every level it is our friends and family members, our actual selves, that we are fighting. I’m not saying anything new here, but it’s what makes addiction so God-awful and such fertile ground for stories — it’s complex and rife with peril and it happens in our living rooms and in our hearts.

GE: Some of the characters in Sweetgirl could have been easily villainized for their dependency on drugs and violent actions, yet you seem to be able to bring a sense of humanity to each that the reader can relate to. What was your process like in creating these characters with such a wide – and human – range of characteristics?

TM: My wife is a death penalty attorney — she represents people on death row and tries to keep them from being executed — and watching her do that work has taught me a ton about the incredibly wide spectrum of actions people are capable of. People who commit violent crimes should go to jail for those crimes, but there is, in almost all cases, a lot more to those people than the worst things they’ve done. I think that’s where I’m coming from with Shelton and Carletta.

GE: Sweetgirl is at times so incredibly heartbreaking that it seems impossible anything in the story could be funny, yet humor is also a large part of the novel. How do you go about finding humor in the situations that seem most bleak?

TM: The funniest book I’ve ever read is Wolf Whistle by Lewis Nordan, which is a fictionalized account of the murder of Emmett Till. The tragedy is profound and deeply felt in that book, and while there is not a single note of false hope, there is redemption in the humor — which is explosive and seems directly correspondent to the depth of despair. I don’t know why that is, or exactly how it works, but I think the funniest stuff often comes from the most painful. I think laughter, real laughter, is a healing agent and probably the most powerful one for me, personally.

GE: When and why did you decide to write this novel? Did it form all at once or did the idea take a while to grow?

TM: It started with the image of a young girl discovering an abandoned baby. The girl was wearing a hooded sweatshirt and I had the sense that she was in as much danger as the baby. I don’t know where the image came from or why I sort of became possessed by it, but that was what I followed — that image and the sense I had that the baby and the young girl would be able, somehow, to help each other.

GE: How do you know when a piece is finished?

TM: Great question. There are two answers: 1) I don’t. 2) Gut feeling.

Both of these things are simultaneously true, I think. Deep down I think I usually know if something is done, and by done I mean it’s ready to be handed off to a reader. Maybe my wife, or a writer friend, maybe my agent or editor. Done in the sense that I’m done with it for now. I think on some level I know when I have reached that place, but it can be obscured pretty easily by fear, or by impatience.

The fear says: You’re not done! (I actually am done, but am afraid it sucks)

The impatience says: You’re done! (I actually am not done, but really wish I was)

Impatience has caused me to rush manuscripts and fear has made me sit on them for too long. I wish there was an easier litmus test. An actual litmus test would be ideal — dip the manuscript in the solution and if it turns blue it’s done, red if it’s not. A digital litmus test would obviously be preferable, but I’d be happy to start with something in a lab. Old school.

GE: What’s next for you?

TM: Working on my next novel, also set in Cutler County. And I’m almost to the point where I can start talking about it in specifics! (Fear and impatience aside…)

**

Travis Mulhauser is from Petoskey, Michigan. He is the author of two works of fiction, most recently the novel Sweetgirl from Ecco/Harper Collins. He lives in Durham, North Carolina with his wife and two children.

May 19th, 2016 |

At Poets & Writers, Kali VanBaale was invited to participate in the Writers Recommend series, where she talks inspiration, The Good Divide, and more:

“On the wall in front of my writing desk, I painted the words of Michelangelo: I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free. This quote has become my guide, my emotional center, my touchstone.”

Check it out here!

Pre-Order The Good Divide (and save 20% off the cover price) here!

May 9th, 2016 |

John McCarthy, whose debut poetry collection Ghost County was published this past March, was recently reviewed at the Chicago Review of Books:

I love the Midwest. I think my work will always be influenced by the Midwest. I feel like the openness of the region lends itself to contemplation. I don’t derive much joy or inspiration from big cities or from being near water like a lot of people do. I know that sounds like a silly thing to say, but I like the ground and I like open uninterrupted space. I like my physicality to be very grounded.

Read the full interview here.

Shop for Ghost County here.

May 6th, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked to author Emily Henry about her book The Love That Split the World, balancing a very complex character, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked to author Emily Henry about her book The Love That Split the World, balancing a very complex character, and more.

**

Rachel Hurwitz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Emily Henry: I’ve spent most of my life here! My childhood was mostly split between Kentucky and Ohio, and after I went to college in western Michigan, I came back here. This area definitely feels like home to me.

RH: Your debut novel, The Love that Split the World, has a sort of fantastical element to it, as the world in which Natalie, the protagonist, lives begins to fade into and out of another world, which in a way, allows time to stop. People often speak of how time stops when you’re in love, so why did you decide that this love story had to be told with time actually stalling?

EH: One of very few other goals I had going into the writing process was capturing the feeling of nostalgia you get at the end of one phase of life and on the cusp of the next, the way you miss things even as they’re happening and can feel both eager and afraid to leave your past behind. One of the reasons I’m so drawn to the young-adult category is that everything in that stage of life still feels earth-shattering, ground-breaking, and big. To me, the fantastical elements of the book all felt like natural extensions or progressions of Natalie’s inner world.

What I remember most vividly about my summer after high school (and to a lesser degree any pivotal time since) is the way that time seems to go all wonky: how it seems to stop and start at random, to slip through your fingers no matter how hard you try to hold on, and to speed up no matter how hard you try to slow it. I didn’t set out to write a scene where time literally stops as two people consider falling in love, even though that happened. I just knew that I wanted to write a book about a highly emotional and sensitive girl navigating an unpredictable, intimidating, and magical world. Time changes its pace when she’s falling in love because, I think, that’s really how it feels. And as summer draws to a close, time stutters and jams up and shuts her off from the boy she’s falling in love with because that’s how that really feels too. Sometimes you are simply carried away by passing time and sometimes you can dig in and hold onto moments a little longer than usual.

RH: Similarly, while The Love that Split the World is, as the title would suggest, a love story, it delves into some much deeper issues such as identity, introspection and hallucinations caused by Natalie’s PTSD. How did you balance interweaving these difficult issues together with the sweetness of young love?

EH: First and foremost, this was the book where I said, “I’m going to write my perfect book.” I threw in just about everything I was interested in reading and thinking about at that time and I knew that meant that it might not register with anyone else the way it did with me. I actually didn’t even tell my agent that I was working on it until it was finished because I needed to be certain I could do it, and the only way to do that was to write the whole book.

I’ve always been a huge fan of books, and shows and movies, that feel like puzzles. I especially love stories that read like all these little pieces are being set out one at a time, and they only slide together at the last moment. I wanted to create that kind of book, where all these seemingly disparate elements come together to tell this epic love story. And I don’t necessarily mean a romance. I wanted to create a full image of all the love in Natalie’s life and how it had conspired to bring her to this point. I didn’t want to erase the bad things–the PTSD, the hallucinations, the complications of her identity and the feelings of loss she has over not knowing her biological family–but I wanted to take this very confused, very complex girl and enable her to step back and see her whole story.

In my own life, I’ve found that a lot of the most painful experiences have, years down the road, led directly to the most beautiful, the most meaningful. In a lot of cases, the struggles of life end up being what forges a person. Natalie has this complicated history, complicated feelings about her past and her future. She has a lot of fear.

I imagine most people have wanted to reach back in their lives to their past selves and comfort them, show them that everything would be okay. I wanted to do that for Natalie, and that meant confronting head on all the things that made her feel Not Okay while also drawing attention to all the bright moments, all the love in her life, new and old.

RH: Since this novel is so complex, did you ever struggle with writer’s block? If so, what was your best remedy for it?

EH: I definitely struggle with writer’s block but did less so with this book than others. Probably moreso, I struggled from logic block. Anytime you’re dealing with time travel, there’s a lot that can go wrong logic-wise. In some cases, I was trying to fix inconsistencies and gaps that my editor spotted and in some, I was just trying to figure out how to explain the logic I understood as this book’s Omnipotent Being. Either way, there were a lot of decisions and changes that couldn’t be rushed. I couldn’t just force out a logical explanation and the harder I focused on certain aspects of the book, the harder they became to grasp.

I honestly think the best personal remedy I’ve found for this and other types of blockage is walking away. Physically doing something different, that pulls your conscious mind away from trying to unravel a plot or logic hole. It seems like sometimes, when you shift gears and do something physically active, your subconscious keeps needling away at all your book’s tangles and knots and it does a better job than your conscious mind. I also think “sleeping on it” is a legitimate move. When you’re stuck like that, the last thing you want to do is walk away and leave an issue unresolved but for me that’s always been the best thing: physical activity, sleep, and plain old thought-incubation time.

RH: What is your favorite way to write? Is there a certain coffee shop you sit in, something you drink, a pen and notebook you use, etc?

EH: I’m so easily distracted that I mostly write at home. I can’t even listen to music unless it’s something ambient that I don’t know well enough to be anticipating certain parts or humming along. I write to the sounds of silence or my dog’s snores and I drink more black coffee than anyone should. I actually had to start brewing half-caf (okay, three-quarters-caf) so that I could drink as much as I wanted to without having a complete meltdown later in the day.

I mostly write on the same couch and I ignore all personal hygiene and health standards. I end up eating things like a handful of mini marshmallows, whatever I can grab on my way to get more coffee, and if I have to pee I might accidentally hold it for two hours if I’m really in the zone. I try to draft very quickly because if I lose interest in a project, I’ll rarely go back to it. I also finish a lot of complete first drafts that I don’t care enough about to revise. I know this is why a lot of authors swear by outlines but any time I’ve tried to write from a thorough outline, I feel sort of like I’m writing a book I just read and it’s not all that fun for me. At this point, I’d rather write three books a year and throw two away. I figure even failing at a book is good practice. I’m sure someday I’ll meet a book that demands to be drafted in a very organized and thorough fashion but for now, this is what I prefer.

I also find it really hard to write without windows! Second-floor windows are ideal because there aren’t as many distractions as on the first floor but you can still get some atmosphere. I always find rainy and snowy days the most inspiring.

RH: What inspired you to become an author? Was there one pivotal moment or was it more of a conglomeration of many events in your life?

EH: I think it was mostly just a love of reading that overflowed into a fan art and fan fiction. I was particularly obsessed with K.A. Applegate’s Animorphs series. I was reading the books as they came out so whenever there was time between releases, I did a lot of drawing and writing. I also made an early realization that while you really need another person to play an effective game of make-believe, you can write (or even daydream) a make-believe scenario entirely on your own.

In the third grade, we were assigned to write short stories and mine was twenty-seven pages long. We had to read them in groups and at least one kid in my group fell asleep while I was reading. I’m not sure why that didn’t discourage me more. I was probably just impressed I’d written something long enough to lull a person to sleep. In the fourth grade, we had to write “autobiographies” of ourselves. We had to guess at our future careers and I said I’d either be an author or play in the WNBA. I had not ever, and still have not ever, played a single game of basketball but I was in awe of bad-ass lady athletes and plus, I think all the popular kids at my school played basketball, so there was that.

Apart from a few years where I was convinced I wanted to be a professional modern dancer, I went on wanting to be an author until I finally was one. I’m sure it was a conglomeration of a lot of things, but primarily an overactive imagination and an obsession with the unlikely brought me here.

RH: Your Twitter profile, which you actively use, is filled with pictures of dogs, giveaways, books, and frankly, happiness. How did social media become such a large part of your literary persona? Do you think that having a social media presence is necessary to being a successful writer in the 21st century?

EH: I would like “dogs, giveaways, books, and frankly, happiness” on my headstone someday! I think social media became important to my literary persona partly because I’m a millennial and partly because I’d been told so many times that it did matter in the 21st century. I actually don’t think this kind of presence is necessary to being a successful writer, but I do think it can be a really special thing. Getting to connect with teen readers who loved, and in some cases felt they “needed,” my book has been one of the most humbling and incredible experiences of my life. So much of a writing life is spent entirely alone, just you and whatever project you’re working on, and it’s both gratifying and surprising to encounter the people who love your book as much as you do.

On the other hand, social media can also be a serious distraction and I’ve found that too much connection to the book world while I’m drafting can stunt that free-flowing creative rush with questions about marketability and competition, and all that. For me, it’s been a big adjustment learning to use social media as a published author rather than unpublished one. I think a good rule for social media, and really any other type of self promotion, is to only use it if you enjoy doing so. Otherwise you might just be wasting valuable writing time and energy.

RH: What’s next for you?

EH: My second book, A Million Junes, will be coming out in early 2017! It’s another genre-bending mystery/romance, this time set in Michigan. If The Love That Split the World was my “love and identity book,” A Million Junes would be my “love and grief book.” It’s as close to my heart as my first book is and I can’t wait to be able to share it.

**

Emily Henry is a full-time writer, proofreader, and donut connoisseur. She studied creative writing at Hope College and the New York Center for Art & Media Studies, and now spends most of her time in Cincinnati, Ohio, and the part of Kentucky just beneath it. She tweets @EmilyHenryWrite.

May 5th, 2016 |

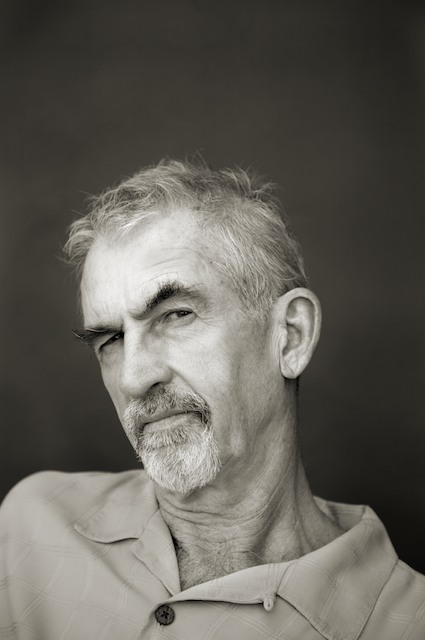

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Jim Krusoe about his novel The Sleep Garden, the underground, the reality of loose ends and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Jim Krusoe about his novel The Sleep Garden, the underground, the reality of loose ends and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the midwest?

Jim Krusoe: A long time ago wrote that to grow up in the Midwest: “…was to watch a glass of milk turn sour. Slow. Inevitable. Reputedly healthful,” and by the Midwest I meant Cleveland, where I was raised. Cleveland later resurfaced as the location of my novel, Erased, and it is the Midwest that I have to thank for my almost pathological need not to be bored, having gotten enough of that unhappy feeling in my first seventeen years there to last a lifetime. I suppose in a way I’ve been running from the Midwest in one way or another ever since.

GE: In you new novel, The Sleep Garden, you write several different interweaving stories following five main characters. What were the challenges, if any, in making their stories fit together?

JK: The characters In The Sleep Garden actually were conceived only after I had figured out what the central images of the novel (holes in a lawn, the burrow, a crossbow, the horrible sixties sitcom, “Mellow Valley”) had to do with each other. Unraveling that question took a couple of thousand pages: false starts, trying things out, testing other images I hoped might replace them. Finally, after creating a literary space fit to host characters, these particular ones stepped up surprisingly quickly and began to tell their stories.

GE: How did you first conceive of the idea of “the Burrow,” the underground apartment building where your characters reside?

JK: The Burrow itself took some time to emerge, although, like Poe, I’m drawn to things that happen underground—basements, caves, and cellars—the literary equivalent of the subconscious. The first incarnation of the Burrow was actually a building called “The Snail Museum.” It was to be a novel about a young girl, or maybe about the guy who ran it, I couldn’t decide. That draft, along with a dozen other attempts, fell through, but in the end I was left holding a building that was basically a lump, like a snail’s shell. I also thought about Kafka’s “In the Burrow,” Emily Dickenson’s “swelling in the ground,” the legend of the Seven Sleepers, and of course Tolkien, whose references to burrows were important to push away from the minds of readers. Also, there’s a great Indian Burial Mound in Moundsville, West Virginia, that I visited a long time ago and left an impression, mostly of seediness.

GE: What inspired you to write about this unique story concept? What do you hope your readers take away from this narrative about life, death, and everything in between?

JK: Of late I’ve become interested in the permeability of my life. By this I mean that my dreams, the things I’ve done, the stories I’ve read and heard, what I’ve witnessed and what I’ve been told I witnessed, as I’ve gotten older, all seem to take on an equal authority and an equal weight in my mind. In this way, my memories of a friend and the actual friend who might be standing in front of me become almost the same. And then, should my friend die (something that happened in the course of this book) I have to ask how much really, has been taken away and how much remains.

GE: An interesting quality of this novel is its lack of closure for some of the characters. How do you feel the loose ends play into the greater meaning of the novel?

JK: In certain ways the lack of closure allows a story to continue after the book is finished. If you were to ask me about my life, I can’t think of a single instance where closure exists, where something is over and done with. Nor should that be the case. I know that Jesus said, “It is finished,” but obviously he was being optimistic.

GE: Your characters are all very unique, from a retired sea captain to phone-sex worker writing a children’s story. How did you go about crafting each distinct personality?

JK: One of the pleasures of writing a novel is that the writer gets to spend a fair amount of time with each character and so find out more about who they are. Characters for me never start full-blown, but build themselves up over the course of months and years until they are revealed as if they exist wholly outside me. Only later comes the surprise that they’ve been a part of me all along.

GE: What aspect of your novel did you most enjoy writing?

JK: I’m ashamed to say it was probably the silliest part: the six episodes of “Mellow Valley,” a sitcom about a pot farm in the sixties. I had been carrying that idea with me, for no good reason, a long time, and then, when I started to write it down, new parts added themselves to the story. For a long time I couldn’t decide whether or not to cut it. But then I decided to wait and see if it had anything to do with the rest of the novel that had yet to be written, and I was surprised to see that it did. Also—and this is important to me—the world is made up of many levels of seriousness and unseriousness; to leave any one of them out is not a true representation of the world, or at least my world.

GE: Have any authors inspired your writing?

JK: I wouldn’t say writers inspire my writing exactly, but they inspire me with their courage, and inventiveness, and their sense of care. And by inspire I mean that they remind me how far I have yet to travel and the impossibility of my ever getting there. On the other hand, the best I can do is make my writing as good as it can be for me.

GE: What’s next for you?

JK: I just finished a novel I had high hopes for but threw out, so I’m back to struggling with images, trying to unlock those I can’t shake and then find some kind of common concern they represent and to discover what they are trying to tell me. Or what I’m trying to tell myself. It’s an interesting state of mind, one where everything we see can be important or significant, part ecstasy, part paranoia, and part frustration. It’s the first step in creating.

**

Jim Krusoe has published five novels and two books of stories, Blood Lake and Abductions. His first novel, Iceland, was published by Dalkey Archive Press in 2002. Since then, Tin House Books has published five novels: Girl Factory, Erased, Toward You, Parsifal, and in 2016 The Sleep Garden. Jim teaches writing at Santa Monica College as well as in Antioch’s MFA Creative Writing Program. He has also published five books of poems.

April 28th, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author John Jodzio about his short story collection Knockout, reconciling shockingness and logic, the satisfaction of performing his work, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author John Jodzio about his short story collection Knockout, reconciling shockingness and logic, the satisfaction of performing his work, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with author Peter Geye about his new book Wintering, the evolution of his writing process, choosing the right narrator and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with author Peter Geye about his new book Wintering, the evolution of his writing process, choosing the right narrator and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Sofia Samatar about her novel The Winged Histories, concentrating on those without a voice, writing across different modes and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Sofia Samatar about her novel The Winged Histories, concentrating on those without a voice, writing across different modes and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with writer Travis Mulhauser about his novel Sweetgirl, humanity in easily-villainized characters, the redemption to be found in humor and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with writer Travis Mulhauser about his novel Sweetgirl, humanity in easily-villainized characters, the redemption to be found in humor and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked to author Emily Henry about her book The Love That Split the World, balancing a very complex character, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked to author Emily Henry about her book The Love That Split the World, balancing a very complex character, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Jim Krusoe about his novel The Sleep Garden, the underground, the reality of loose ends and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Jim Krusoe about his novel The Sleep Garden, the underground, the reality of loose ends and more.