Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Martin Seay about his book The Mirror Thief, coordinating three separate stories into one novel, encouraging empathetic openness through fiction, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Martin Seay about his book The Mirror Thief, coordinating three separate stories into one novel, encouraging empathetic openness through fiction, and more.

**

Lauren Stachew: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Martin Seay: I’m a relative newcomer to the Midwest, having grown up in the western suburbs of Houston. (Specifically in the town of Katy; “the western suburbs of Houston” could plausibly describe an area the size of Connecticut.) My spouse Kathleen Rooney and I bounced around the country for a while — Washington DC, Boston, Provincetown, Tacoma, WA — but we’ve lived in the Edgewater neighborhood on the far north side of Chicago since 2007. Kathleen grew up in the Woodridge–Downers Grove area, and her family hails from Nebraska, so she’s credentialed as a native Midwesterner.

Regional identity — and Midwestern identity specifically — is something that I think about a lot. This is totally unscientific on my part, but I can’t help but think that there’s something in the tension between the natural and built environments in every region that affects the assumptions and the expectations of the people who grow up there, in ways that are so fundamental as to be nearly invisible. I’ve often been struck by how completely domesticated the Midwestern landscape is: just about every square inch of dry land has been shaped and reshaped by human habitation for so long that every space feels like a social space, and therefore one always feels as though one is within the bounds of some society or another here. (In the Pacific Northwest, by contrast, it never felt like we were really part of a society — or at least it felt as though society was something that everyone could exit at will and without much of a fuss.)

LS: In what ways do you feel that living in the Midwest – specifically Chicago – have influenced your writing?

MS: I should confess that the vast majority of my recently-published novel was written before I arrived in Chicago. Since I’ve been living here, most of the writing I’ve done has been essays and criticism of various sorts. (I don’t think this has been a direct consequence of living in Chicago, but rather just of having a full-time office job and an hour-long commute.) I’m about to return to fiction after quite a bit of time away, and I’m interested to see the effect that Chicago has on whatever I end up doing.

One quality of Chicago that has had a significant impact on Kathleen’s and my lives is the vibrancy and openness of the literary scene here, which overlaps in unforced, organic, mutually-beneficial ways with the theater scene, the music scene, the dance scene, the comedy scene, the art scene, etc., and produces a ton of interesting and hard-to-categorize work that lands in the spaces between those more recognizable forms. Beyond the fact that living here has made us aware of a bunch of cool stuff, we have also met a bunch of great people who are very receptive to each other’s pursuits and supportive of each other in creative, professional, and personal terms.

In some ways the fact that many of the city’s most prominent institutions seem to be in danger of collapsing — or of not collapsing, depending on the institution — seems to empower and inspire activities at the small, nimble, independent, subcultural level, which is cool. I think most of us would happily swap some of this great art for a city that’s more just and more functional, though.

LS: Your debut novel, The Mirror Thief, weaves together three separate stories into one novel, all set in three different versions of Venice. Some reviewers have called this skill “almost miraculous.” How did you manage these various threads as you were writing? Did you draw out maps or charts?

MS: It helped a lot that I had the structure first. Before I had any characters, or much in the way of a plot, I knew I would be writing a narrative split evenly between Renaissance Venice, Beat-era Venice Beach, and more-or-less present-day Las Vegas. I also knew that certain locations or people would appear: the Venetian casino, the Guggenheim Hermitage Museum, and a flooded Mormon town in the 2003 chapters; Alexander Trocchi, Lawrence Lipton, and the Venice West Café in 1958; and Giambattista della Porta, Giordano Bruno, a glass factory, and a bookstore in 1592. I came up with plots that would connect all these elements, and then I came up with characters who could follow the paths I had laid out. Consequently I always knew where I was going (although I was a little foggy on how long it would take me to get there).

I outlined backstory more rigorously than I did the three main storylines that run through the book. I definitely used outlines to keep myself straight on the action taking place in the narrative present, but I tried to be sparing with them; I didn’t want the plot to become too functional, or too much of a glide path for the characters. All my best discoveries came as a result of slowing myself down, not speeding myself up.

LS: What made you choose Venice as the unifying “setting” for this novel?

MS: Venice came first: I knew I wanted to write about Venice before I knew anything else about the novel, or even that it was a novel. I had been to Venice for a couple of days in the late ’90s while doing the post-collegiate-tour-of-Europe thing, and it stayed in my head as a place I that wanted to use as a subject and a setting. (I also knew, of course, that a bunch of people had beaten me to the punch—including heavy hitters like Henry James, Thomas Mann, Daphne du Maurier, and my esteemed former teacher Jane Alison — but I decided to think of this as more of an advantage than a problem.)

A lot of things about the city fascinated me (and still do) — aspects that make it different from any other place, and contrast with other European cities in interesting ways: the primacy of canals over streets, the near-total absence of fortifications, and the distinctively light, permeable, curvilinear nature of the built environment, to name a few. The one fact I learned about Venice during my first visit that struck me the most is that it is not, strictly speaking, built on islands: most of its present-day land was constructed by driving masses of wooden pilings through the lagoon’s sandy bottom into the clay beneath, and almost all of its churches, palaces, squares, and streets are (somewhat tenuously) supported by these pilings. The city is literally built on the water. The blankness of the canvas that the Venetian engineers were working with and the necessary deliberateness of their methods — along with Venice’s complex and ambiguous thousand-year history as a functioning republic — led me to think of it as the city that’s most purely expressive of the will and values of the community that created it: a city grown in a Petri dish, basically. Therefore it seemed like a good lens through which to view other cities, and other human undertakings.

LS: Many reviewers have drawn similarities in your novel to the writings of authors such as David Mitchell, Umberto Eco, and Italo Calvino. Were any of these authors inspirations to you?

MS: Invisible Cities definitely was; I borrowed a passage from it — a fairly cryptic and mind-blowing exchange between Kublai Khan and Marco Polo — as the epigraph of my book. But that’s the only thing of Calvino’s that I’ve read in its entirety: I picked it up shortly after I started The Mirror Thief because I thought it would help me get my head straight about Venice from a conceptual and metaphorical standpoint, which it did. I was drawn to it both because of its unusual engagement with Venice as a subject and because I had recently been interested in the Oulipo, the mostly-European group of avant-garde writers who used various restrictions and quasi-mathematical structures as strategies for generating literature; Invisible Cities comes from the period of Calvino’s participation in the group. (The Mirror Thief didn’t end up being very Oulipian; the only real restriction is the fact that I never used the word “Venice” — or any form of it: no venetian blinds, no Venezuela — in the book. Oulipian novels like Invisible Cities and Harry Mathews’ under-appreciated Cigarettes also inspired me to deploy certain recurring images or concepts as generative and organizing devices — mirrors, mosaics, excrement, pirates, pelicans, mercury, Mercury, the various stages of the alchemists’ Great Work, etc. — but my use of them was not remotely rigorous enough to meet Oulipian standards.)

So far as Mitchell and Eco go, I really enjoyed Cloud Atlas, but it wasn’t an influence: I didn’t read it until after I had finished the manuscript of The Mirror Thief, and it’s still the only thing of Mitchell’s that I’ve read. This is maybe going to sound lame, but although I have definitely been strongly influenced by my idea of what an Umberto Eco novel is like, I’ve never read one: I have copies of Foucault’s Pendulum and The Name of the Rose that I’ve been moving from apartment to apartment with me for years, but I’ve never read either, despite several attempts.

The novels that were probably the biggest influences on The Mirror Thief — to my way of thinking, anyway — are All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy, My Name Is Red by Orhan Pamuk, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami, Cat’s Eye by Margaret Atwood, and The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler. From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell ended up being something I thought about a lot while I was writing; so did House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. Books by Elmore Leonard, Dennis Lehane, and Alan Furst helped me figure out the genre mechanics of the 2003 and 1592 sections. To nail down some of the cadences and the lexicon of the 1592 sections, I also reread a fair amount of Shakespeare. A few nonfiction books were very inspirational, particularly Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century by Greil Marcus, The Optical Unconscious by Rosalind E. Krauss, and Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters by the painter David Hockney, which sounds like an instructional book but isn’t.

LS: You spent nearly six years writing The Mirror Thief – what was the most difficult part of the writing process for you?

MS: The most difficult and rewarding part of the process was figuring out the three main characters: working out their backstories, but also and especially developing an understanding of how they would uniquely perceive the world.

This is not something that comes easily for me: I’m a concept-driven writer, and plot and character tend to show up late in the game. I reached a point early on where I needed to pretty much stop writing and just spend a couple of years trying to imaginatively inhabit the fictional world of the book, thinking really hard about my characters’ embodied experience of that world: to consider, for instance, not only what walking down the Las Vegas Strip in March of 2003 would have been like, but specifically what it would have been like for a 39-year-old partially-disabled retired U.S. Marine who spent the previous night sleeping in a chair at Philadelphia International Airport.

Of the many great things about fiction, I think one of the best is its capacity to encourage empathetic openness to others, and to do so by modelling that openness. I wanted to honor that capacity by taking the responsibility of depicting my imaginary people seriously.

LS: What advice would you give to authors who are trying to have their first novel published?

MS: If you can keep your manuscript under 700 manuscript pages, I recommend doing so. Trust me on this one.

But seriously…I should probably mention that The Mirror Thief took me a little under six years to write, and a little over seven years to find a publisher for. This was due in large part to the fact that I was circulating the manuscript in the midst of a recession that clobbered the publishing industry, but there’s really never going to be a time when the major trade houses are going to be tripping over each other to hand out seven-figure advances to unknowns with really long first novels, even if those novels do include swordfights (which, for the record, mine does).

I’m hardly an expert on the publishing industry based on my limited and rather atypical experience, so I can’t provide much in the way of practical advice beyond one very general recommendation: it’s a good idea to develop strategies for keeping your head straight when you move from a process in which you have total, godlike control (i.e. the process of writing) to one in which you have approximately zero control (the process of seeking publication). More specifically, I’d suggest that your strength in navigating the latter process will come from your rigor during the former process: you should be damn sure that you’ve written the book you wanted to write, because confidence in your manuscript will sustain you through long stretches of radio silence and help you make productive use of the feedback you receive from agents and editors.

LS: What’s next for you?

MS: Great question! I have a few ideas for new novels that I’m playing around with; if past experience is any guide, I’ll need to live with them awhile before I know which I’ll pursue. In the meantime, I have several criticism projects — writing on music and film — that I’m excited to work on. I’m very fortunate that The Mirror Thief has gotten quite a bit of positive attention, and it seems to be bringing some interesting opportunities my way. So far it’s been rewarding to just remain open to whatever comes along, and enjoy it while it lasts.

**

Martin Seay’s first novel, The Mirror Thief, was released by Melville House in May. Other writing has appeared recently in Electric Literature, Lit Hub, Publishers Weekly, MAKE, and The Believer. Originally from Texas, he lives in Chicago with his spouse, the writer Kathleen Rooney.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Martin Seay about his book The Mirror Thief, coordinating three separate stories into one novel, encouraging empathetic openness through fiction, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Martin Seay about his book The Mirror Thief, coordinating three separate stories into one novel, encouraging empathetic openness through fiction, and more.

Daniel Smith’s pieces “Father’s Day” and “Northwestern Illinois In June” appear in

Daniel Smith’s pieces “Father’s Day” and “Northwestern Illinois In June” appear in  Joe Sacksteder’s story “Prep Work” appears in

Joe Sacksteder’s story “Prep Work” appears in

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Julie Lawson Timmer about her novel Untethered, complicated familial bonds, juxtaposed sentiments toward one’s Midwestern hometown, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Julie Lawson Timmer about her novel Untethered, complicated familial bonds, juxtaposed sentiments toward one’s Midwestern hometown, and more.

Garrett Dennert’s story “Trisomy” appears in

Garrett Dennert’s story “Trisomy” appears in

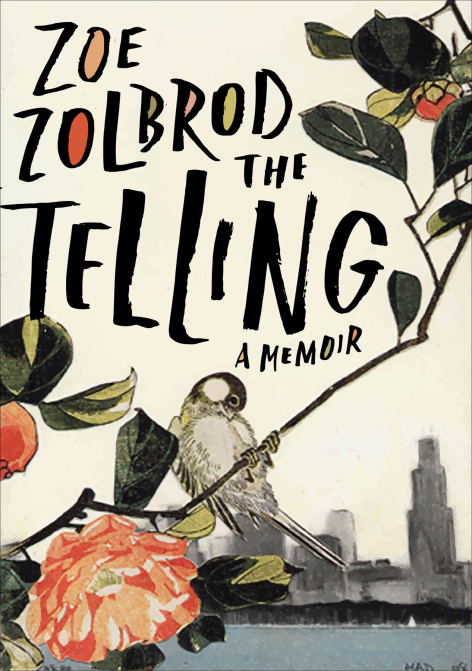

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Zoe Zolbrod about her memoir The Telling, making the internal external, readers’ responses to a multifaceted literary work, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Zoe Zolbrod about her memoir The Telling, making the internal external, readers’ responses to a multifaceted literary work, and more.

Sharon Kunde’s pieces “Illinois Elegy (Elegy #15)” and “Prodigal” appear in

Sharon Kunde’s pieces “Illinois Elegy (Elegy #15)” and “Prodigal” appear in