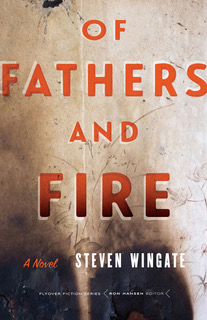

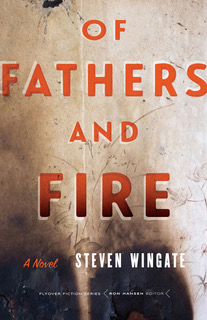

Midwestern Gothic Assistant Editor Marisa Frey talked with author Steven Wingate about his newest book, Of Fathers and Fire; how we construct our own identities; and the changing landscape of American politics.

**

Marisa Frey: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Steven Wingate: It’s long-standing and complex. For the past eight years, I’ve been living in South Dakota, but I’ve spent much of my life in the eastern half of Colorado—the non-glamorous part without mountains. My teen years unfolded in much the same environment you see in Of Fathers and Fire, though my town was bigger and closer to Colorado Springs. Still, I could look out my back window and see nothing but empty plains that stretched on for six hundred miles to Kansas City. Things were flat and we were not only isolated from coastal influences but very aware of that isolation.

So I’m not a Midwesterner in the way that someone from Ohio might claim to be, but I definitely consider myself a Great Plains writer and feel like part of the “Midwest conversation” on that basis. There’s tremendous overlap between the “Great Plains” and the “Midwest”—just look at a few maps of each geographical construct and see how similar they are. But there’s also a cultural overlap, that sense of separateness from the coastal edges of the nation. Both the Midwest and the Great Plains are part of “flyover country,” and it’s appropriate that this novel is part of the Flyover Fiction series from the University of Nebraska Press. I’ve got a lot to say about the region, and that series—which is dedicated to Great Plains literature—really allows the book to be seen in its rightful context.

MF: You said you took notes on Of Fathers and Fire for ten or twelve years. How did the novel change as you grew as a father?

SW: When I first started in on the material, my oldest son wasn’t even born. Now he’s old enough to fight me emotionally and define himself against me the way young men do, and my younger son is getting into the same territory. Seeing this unfold in my own life has given me a lot more insight into Tommy’s relationship with his fathers. (I make that word intentionally plural, because one father is real and the other imaginary, but both affect him.) Over the years I’ve been able to see how father-son relationships evolve and how sons define themselves both with and against their fathers at the same time. It’s something I missed out on personally, since my dad died when I was young, and I think I had to become a father myself to understand that process.

I’ve grown up in those years too, and my understanding of what fatherhood involves has developed a great deal. When I first started the novel I couldn’t write Tommy’s father, Richie Thorpe, as anything but a monolithic character viewed from the outside. He was a black box, a closed-off creature I could only write about. But as time went on and I had more experience as a father, I could see with his eyes. The thing that truly helped me get the book finished was my kids reaching the age where we could talk about my mistakes and failings. This was absent between Tommy and Richie in earlier incarnations of the novel, and looking back that was a fatal flaw. Only when I got to the point where I could talk with my kids about my own weaknesses could I actually pull off this book.

MF: Of Fathers and Fire takes place in a small, all-white town in Colorado in 1980, during the Iran hostage crisis. How did you navigate writing about xenophobia and why was it important for you to include?

SW: I felt I had to include it because it was realistic to the time, which was quite different from ours demographically and culturally. In 1980, whites accounted for 83 percent of America’s population; now it’s estimated at around 73 percent. Yet even back then, there were people saying they wanted to “take our country back” from the non-white “invasion” that was supposedly overtaking America. There were plenty of white people in my immediate orbit at that time who refused to hang around with “those people”—meaning non-whites—and if whites did hang around with “those people,” they were seen as decidedly inferior by those who held their whiteness especially dear. This kind xenophobia permeated the socioeconomic strata that I’m writing about in Of Fathers and Fire.

SW: I felt I had to include it because it was realistic to the time, which was quite different from ours demographically and culturally. In 1980, whites accounted for 83 percent of America’s population; now it’s estimated at around 73 percent. Yet even back then, there were people saying they wanted to “take our country back” from the non-white “invasion” that was supposedly overtaking America. There were plenty of white people in my immediate orbit at that time who refused to hang around with “those people”—meaning non-whites—and if whites did hang around with “those people,” they were seen as decidedly inferior by those who held their whiteness especially dear. This kind xenophobia permeated the socioeconomic strata that I’m writing about in Of Fathers and Fire.

The underlying issue there is the question of who gets to call themselves an American, which never goes away and occasionally forces itself to the head of our national conversation. For me, this is a personal issue. My maternal grandparents came over from Poland in the early 1900s—a time when Poles were reviled here because a Pole assassinated President McKinley in 1901—and they never became U.S. citizens. It bothers me deeply to see the kind of hatred America has for immigrants, but sadly it’s nothing new.

Today’s xenophobia feels much more virulent than it did in the 1980s, and in fact a lot more like it did when my Polish grandparents came to America. I encourage anyone who thinks this level of hostility is unique to the Trump era to visit the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration and see what the headlines had to say about immigrants then. It actually makes today seem tame by comparison. But this current has always been part of America’s identity, and in the novel, I didn’t feel any choice but to look at it straight on.

MF: The political situation in the novel—which takes place in an era that you’ve said introduced the “weaponization” of Christianity—is similar to today’s. Do you think we’ve learned anything from the past?

SW: I wish I could say we’ve learned something positive, but I think what we truly learn from the past is how to perform the same kind of cruelties toward our fellow humans with greater efficiency. We do things tentatively the first time, then back off, then do it with more violence and precision.

Version 1.0 of the weaponization of Christianity—at least in my lifetime, since I’m sure there were other versions before then—came during the “Reagan Revolution,” partly as a backlash to Roe v. Wade. There was a very “us vs. them” attitude among the religious right, a sense that they wanted to “take back America” and return it to its glory days by subjecting it to the moral code of a very punitive form of Christianity.

Flash forward thirty-six years and you have Version 2.0, the “Trump Revolution” if you will, which even stole its main slogan from Reagan’s campaign. “Let’s Make America Great Again” was a Reagan slogan, and Trump simply took off the first word. Version 2.0 of weaponized Christianity has no problem putting kids in cages or relentlessly screwing over the poor people that the Gospels tell us to help. Those with that mindset don’t care if transgendered people kill themselves out of despair or if economic inequality is the greatest it’s been since right before the Great Depression. They simply want “their” country back, and in trying to do that they’ll pull out all the same stops they did during Version 1.0 but go for the jugular this time.

It’s as if 1980 was a dress rehearsal, and today is the real show. Today’s crowd hates the same people as yesterday’s (especially Muslims) and believe fervently that they’re saving America from itself. It’s hard to watch the country I love eat itself alive in the same way twice, but here we are.

MF: Tommy plays the saxophone and dreams of going to New York because that’s what his made-up father did, but he’s able to move elements of the earth and is interested in cars, like his biological father and grandfather, raising the question of how a person constructs their identity versus how their identity is constructed for them. How do you reconcile these?

SW: I could only try to reconcile all that emotional material by writing a novel—I needed all that space because there was no way I could do it more succinctly. The construction of identity is one of the great subjects of fiction, and the bildungsroman tradition (which this novel is a part of) is dedicated to it. Tommy’s adult character is coming into being before our eyes, and that’s fascinating for me to write because there are so many layers to it.

As you mention, there’s that biological layer—who we are even if we think we’re something else, which in the book is embodied in all the similarities between Tommy and the biological father he’s just met. There’s another layer we get by osmosis, simply from absorbing the time and place we live in. And finally there’s the layer of identity we create through identification or opposition with our own families and our cultures, like Tommy’s embrace of bebop jazz or his rejection of the knee-jerk militarism that’s all around him in Suborney.

Often we can’t tell which layer our own attributes stem from. Tommy’s love of muscle cars is almost genetic, yet it’s also the result of his class upbringing and geography. The fact that it’s a little bit of both fascinates me, and honestly, that’s one of the reasons I write fiction. When I was Tommy’s age I used to want to be a primatologist like Jane Goodall, but when I discovered literature I realized that human beings are vastly more interesting because of our identity formation. Showing Tommy’s transition from being the son of an imaginary sax player to the son of a criminal with limited control of the elements was the most fun I’ve ever had writing.

MF: Of Fathers and Fire is as much about Tommy’s relationship with his mother, Connie, as it is about the one he’s just starting with his father. What was the most difficult part of portraying Tommy and Connie’s relationship?

SW: Not making Connie merely the “bad guy” in the book was my biggest challenge. She’s standing in Tommy’s path and has lied to him in ways that are difficult to forgive, but as misguided as she’s been she’s acted out of love for him.

Writing her love for Tommy wasn’t the hardest part, though. It was finding the ways that Tommy loved her, even after her lies are exposed. In early versions of the novel he simply wanted to punish her. But the longer I spent on their relationship, the more I saw that Tommy genuinely wanted a stronger one with her. He desires honesty for her, a coming clean that she’s denied herself. The easy thing to do would have been to let him simply hate her. The harder but more rewarding thing was to let him love her while being unable to tolerate her.

MF: You’re an English professor at South Dakota State University. How does teaching influence your writing?

SW: My mindset with my students is a lot like my mindset with myself. The writing process always unfolds much more slowly than you’d like, 95 percent of what you’ll do is make sentences better, and the biggest trick is getting a tale to unveil itself. Every suggestion I give to my students is going to apply someday to my own work. Most of the time what I’m suggesting to them are narrative opportunities—”what-ifs” within a draft that might open up the work further and give it more depth, more chaos. Without chaos, fiction has no engine at its center.

Because I’m always finding ways to push my students’ writing deeper into its chaos, it helps me do the same with my own. Teaching writing and having to articulate that the development process has made me a much more aware writer than I would have been without it. Also, having to say things that are sometimes difficult to living human beings has taught me to be kinder to myself, too.

MF: What are you reading right now?

SW: One regret I have about the teaching life is that reading for pleasure has really fallen off for me compared to when I was younger. I read for a living, and since most of that work isn’t fully formed, it can require a lot of energy to get through. I spend a lot of time looking at student writing that I can tell from page one isn’t working, then trying to be constructive and encouraging, saying “What could make this stronger?” or “Where’s the real story here?” That means I don’t always have energy or inclination left over to crack open a book.

I was warned about that phenomenon when I went into teaching and advised to develop a reviewing practice to make sure I had some skin in the game of contemporary literature. I followed that advice and I’m usually reading something for Fiction Writers Review, where I’ve been involved for almost a decade, or one of the other venues I work with. Right now I’m reading Cape May, a debut novel by Chip Cheek due out at the end of April, and I’ll interview him for FWR. It’s a great way to get to know other authors—or in Chip’s case, get to know them better—and it really helps to lessen the isolation I feel being in a such a rural environment.

The other thing that helps me overcome that reading gap is audiobooks since they don’t give me the eye fatigue I get from print books. (I love print books, by the way—I’m not one of those “death of the book” people by any stretch.) Audiobooks let me shut off my eyes and listen with my imagination, and I’m usually listening to a horror novel as I walk the dog, do the dishes, and (if I’m lucky) work out. Horror—especially the kind that verges into fantasy) lets me sink into the supernatural elements I love, and I’m learning a lot from Stephen King, Joe Hill, Clive Barker, Victor Lavalle, Neil Gaiman, Andrew Michael Hurley, etc. I’m poking away at a horror novel and consider it all their fault.

MF: What’s next for you?

SW: Now that I’ve tasted the novel, after many years of being a genre nomad who worked in all sorts of forms from poetry to gaming, all I want to do is write novels for a while. The next one coming out of the pipeline is set in eastern South Dakota, which is more properly Midwestern than Colorado. Nobody can argue with South Dakota as part of the Midwest, right? At least the eastern half, without the mountains.

But my characters aren’t Midwestern, which puts a twist on things. While a lot of literature the Great Plains and Midwest is about people who are deeply rooted there, almost part of the soil, my next novel is sort of a 21st-century immigration story. My protagonists are from the coasts—he’s from Boston and she’s from Los Angeles—and they end up in South Dakota like stray dogs to deal with their ghosts and demons: prescription pharmaceuticals, infertility, domestic violence, and an inability to let go of the dead.

I’m putting the finishing touches on this novel as Of Fathers and Fire is making its way into the world, and I hope the new one will also be part of the Flyover Fiction series because my main body of work is so heavily connected to the Great Plains. But I don’t want to talk about it too much for fear of jinxing it, because I haven’t sent it in yet. I think it’s finished, though I need to see Of Fathers and Fire set sail in the world before I can decide if it is or not. I’ll know in a month or two.

**

Steven Wingate‘s works include the novel Of Fathers and Fire, published by the University of Nebraska Press in April 2019, the digital memoir daddylabyrinth, which premiered at the Singapore Art/Science Museum in 2014, and the short story collection Wifeshopping, which won the Bakeless Prize from the Bread Loaf Writers Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2008. He is an associate professor at South Dakota State University and associate editor at Fiction Writers Review.

Chad Koch: I’ve found that writer’s block can be cured by changing focus from “I need to write a story” to “let’s just write 1,500 words today.” I was actually against this idea for a while because I thought I’d just be wasting time, but I recently did NaNoWriMo and it helped me finish my novel. In a lot of ways just getting something—anything—on the page moves things forward. Switching to word count also stifles your inner critic because now you measure yourself by a number of words, which is black and white (you either hit your word count or you don’t).

Chad Koch: I’ve found that writer’s block can be cured by changing focus from “I need to write a story” to “let’s just write 1,500 words today.” I was actually against this idea for a while because I thought I’d just be wasting time, but I recently did NaNoWriMo and it helped me finish my novel. In a lot of ways just getting something—anything—on the page moves things forward. Switching to word count also stifles your inner critic because now you measure yourself by a number of words, which is black and white (you either hit your word count or you don’t).

M. Drew Williams: I consider my process to be one long, drawn-out method of combating writer’s block. First and foremost, I try to read for at least two hours every day: The less time I spend reading, the less likely I am to gain the inspiration needed to write anything of merit. Throughout my work week, I try my best to jot down a few interconnected lines (or interesting words). By Saturday, I often force myself to write a poem, and even though I am not always successful in my efforts to do so, the effort itself at least gets me one step closer to actually writing a worthwhile poem.

M. Drew Williams: I consider my process to be one long, drawn-out method of combating writer’s block. First and foremost, I try to read for at least two hours every day: The less time I spend reading, the less likely I am to gain the inspiration needed to write anything of merit. Throughout my work week, I try my best to jot down a few interconnected lines (or interesting words). By Saturday, I often force myself to write a poem, and even though I am not always successful in my efforts to do so, the effort itself at least gets me one step closer to actually writing a worthwhile poem.

Danielle Lazarin: Believe in process over product. Don’t obsess over the number of words you put down or publications. Committing the time to the work is the most you can do, the little thing you can control. There’s no guarantee that you’ll produce what you expect in that time, but getting comfortable with being in that chair in a disciplined way is the best you can do, and it’s enough—whatever amount of time that is. Over time, that collective work will end up in your product, even if you delete a lot of the words.

Danielle Lazarin: Believe in process over product. Don’t obsess over the number of words you put down or publications. Committing the time to the work is the most you can do, the little thing you can control. There’s no guarantee that you’ll produce what you expect in that time, but getting comfortable with being in that chair in a disciplined way is the best you can do, and it’s enough—whatever amount of time that is. Over time, that collective work will end up in your product, even if you delete a lot of the words.

SW: I felt I had to include it because it was realistic to the time, which was quite different from ours demographically and culturally. In 1980, whites accounted for 83 percent of America’s population; now it’s estimated at around 73 percent. Yet even back then, there were people saying they wanted to “take our country back” from the non-white “invasion” that was supposedly overtaking America. There were plenty of white people in my immediate orbit at that time who refused to hang around with “those people”—meaning non-whites—and if whites did hang around with “those people,” they were seen as decidedly inferior by those who held their whiteness especially dear. This kind xenophobia permeated the socioeconomic strata that I’m writing about in Of Fathers and Fire.

SW: I felt I had to include it because it was realistic to the time, which was quite different from ours demographically and culturally. In 1980, whites accounted for 83 percent of America’s population; now it’s estimated at around 73 percent. Yet even back then, there were people saying they wanted to “take our country back” from the non-white “invasion” that was supposedly overtaking America. There were plenty of white people in my immediate orbit at that time who refused to hang around with “those people”—meaning non-whites—and if whites did hang around with “those people,” they were seen as decidedly inferior by those who held their whiteness especially dear. This kind xenophobia permeated the socioeconomic strata that I’m writing about in Of Fathers and Fire.

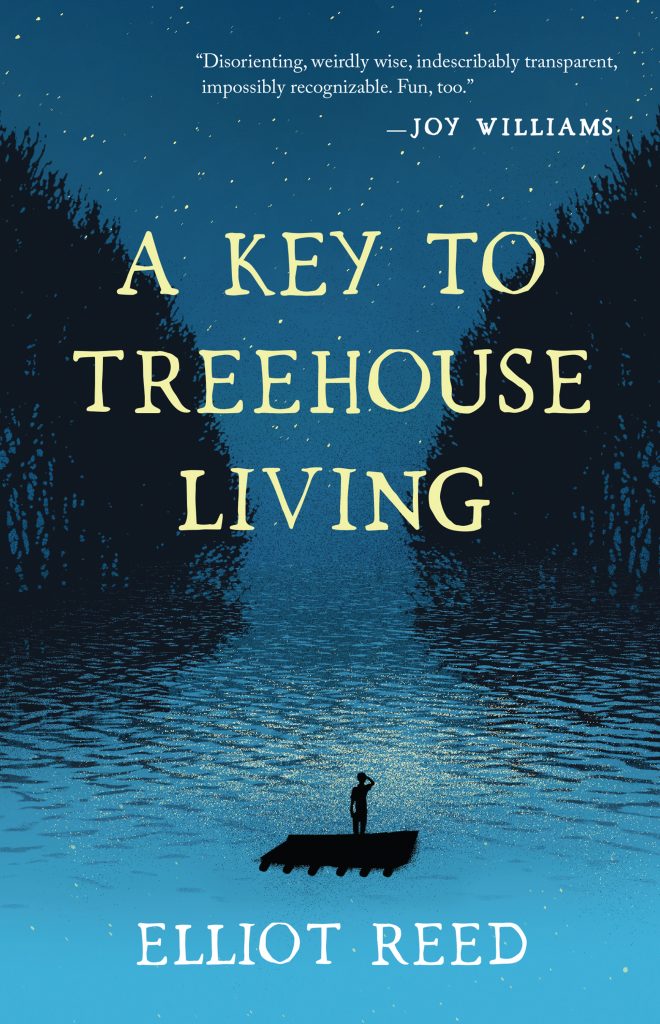

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ariel Everitt talked with author Elliot Reed about his debut novel A Key to Treehouse Living, the importance of creativity to children and adults, and the myths we live by.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ariel Everitt talked with author Elliot Reed about his debut novel A Key to Treehouse Living, the importance of creativity to children and adults, and the myths we live by.